I just got back from New Orleans where I read a paper at the 2010 conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music US Chapter: “Births, Stages, Declines, Revivals.” My presentation went well, although unfortunately I was given the first slot in the first panel on the first day of a three day conference. (8:30 AM on Friday morning!) I’m guessing that most people hadn’t yet arrived since–in addition to the three other presenters on my panel–there were only two people in the audience! Oh well.

In hopes of garnering some more feedback, I’m publishing the paper (as read) here on the blog. As usual, this remains a work in progress.

Click here to download a PDF version of the paper. (Slides and visual examples appear at the end of the PDF.) Or, follow the jump to read the html version.

Temporality, Intentionality, and Authenticity

in Frank Zappa’s Xenochronous Works

[Click the images to see the slides at full resolution.]

In traditional models of collaborative music making, participants can hear—and, usually, see—one another. Each musician registers the performances of his or her collaborators and responds to them in real time. Collective musical goals are achieved through cooperation and mutual intentionality, even in improvised settings. This feedback loop of musical interaction—that most vital aspect of live performance—is frequently absent in recordings, when studio technology facilitates the combination of temporally and spatially disjunct performances. Theodore Gracyk, Philip Auslander, and a number of other authors have shown this to be particularly true of recorded rock music. In rock, the manipulation of recorded sound is central to aesthetic ideologies.

Lee B. Brown defines “works of phonography†as “sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one.â€[1]

Documentary recordings may—and often do—comprise the constituent ingredients of such works; but overdubbings, tape-splicings, and other editing room procedures deliver to the listener a virtual performance, an apparition of musical interaction that never took place. Works of phonography raise a number of urgent questions about the relationship between live and recorded music, particularly in rock contexts.

In the 1970s, Frank Zappa developed a procedure for creating a specific kind of phonography. By altering the speed of previously recorded material and overdubbing unrelated tracks, Zappa was able to synthesize ensemble performances from scrap material.

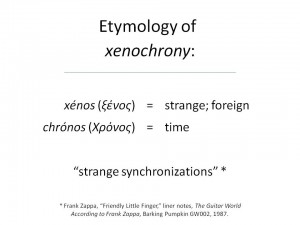

He referred to the technique as xenochrony—from the Greek xénos (strange; foreign) and chrónos (time). Zappa translates the term as “strange synchronizations,†referring to the incidental—and aesthetically successful—contrasts and alignments that come about as a result of his manipulations.

Zappa describes the effect of his “strange synchronizations†in a 1988 interview conducted by Bob Marshall:

the musical result [of xenochrony] is the result of two musicians, who were never in the same room at the same time, playing at two different rates in two different moods for two different purposes, when blended together, yielding a third result which is musical and synchronizes in a strange way.[2]

By combining separately-recorded performances, such music easily meets Brown’s criteria. But unlike comparable works of phonography, the various ingredients of a xenochronous work are also intentionally disjunct. Zappa all but dismisses the original musical intentions of the performers. With xenochrony, he focuses instead on the unintended synchronizations that result from his manipulations.

In many cases, rock artists and producers mask their methods. Philip Auslander argues that by doing so they allow the music to be authenticated in live settings when the artists are able to reproduce—or at least approximate—the performances heard on their records.[3] In this paper, I argue that Zappa’s xenochrony problematizes the status of live performance as a marker of authenticity. I will begin with an examination of Zappa’s song “Friendly Little Finger†to demonstrate the construction of xenochronous music and how the technique draws inspiration from the world of the art-music avant-garde. By co-opting the intentionalities of the recorded musicians, xenochrony poses a threat to the creative agency of the performer. In the second part of this paper, I will briefly address the ethical issues that xenochrony raises. Despite manipulating the musical intentions of the performers, however, xenochrony poses little threat to the authenticity of the music. I will conclude by proposing that Zappa replaces traditional sources of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn from the art-music avant-garde.

I. Temporality

To the uninformed listener, there is no strong evidence to suggest that Zappa’s “Friendly Little Finger,†from the 1976 album Zoot Allures,[4] is anything other than a recorded document of an ensemble performance.

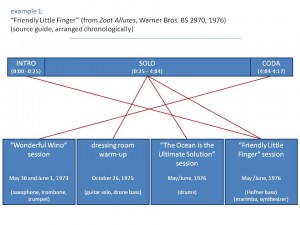

The piece begins with a brief introduction featuring a repeated riff performed on guitar, marimba, and synthesizer. An extended improvisation with electric guitar, bass, and drums fills out the lengthy middle section before the track concludes with a quotation of the Protestant hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves,†arranged for a trio of brass instruments. Despite its apparent normalcy, however, “Friendly Little Finger†combines materials from four distinct sources spanning three years of Zappa’s career.

The primary recording—a guitar solo with a droning bass accompaniment—was recorded in the dressing room of the Hofstra University Playhouse as a warm-up before a performance on October 26, 1975. Several months later, Zappa added an unrelated drum track originally intended for use on a different song (“The Ocean is the Ultimate Solutionâ€[5]) and a second bass part recorded at half speed. These three recordings, all appearing in the middle solo section, comprise the xenochronous core of the piece. To this, Zappa superimposed two additional recordings. The introduction comes from the same session as the added bass part, and the coda was recorded several years earlier, during a session for the song “Wonderful Wino.”

As Example 1 makes clear, the result of Zappa’s editing is a moderately dense network of temporally disjunct recordings. How is it that such seemingly disparate recordings happened to come together in this way? What inspired Zappa to take such an approach to manipulating recorded sound? Of course, examples of overdubbing in American popular music can be found at least as far back as the 1940s—recall Sidney Bechet’s One Man Band recordings in which each instrument was performed separately by Bechet himself. But while such tricks had become old hat by the mid 1970s, xenochrony stands out for it also has obvious ties to the twentieth-century art-music avant-garde.

Despite his continuing reputation as a popular musician, Zappa was remarkably well read in the theoretical discourse surrounding avant-garde art music, particularly with regards to musique concrète and tape music. He expressed an ongoing interest in John Cage’s chance operations, for example, trying them out for himself by physically cutting recorded tapes and rearranging the pieces at random for the 1968 album Lumpy Gravy.[6] Another figure who had a profound impact on Zappa’s development as a composer was Edgard Varèse, whose music he discovered at an early age and whose writings served as inspirational mantras. Given this fascination with the avant-garde, xenochrony may be best understood as a conscious attempt by Zappa to model himself on these influential figures. His own approach to music and composition would therefore require an analogous theoretical foundation.

Xenochrony is closely tied to Zappa’s conception of temporality. Zappa often described time as a simultaneity, with all events occurring at once instead of chronologically. Toward the end of his life, in an oft-quoted conversation with cartoonist Matt Groening, Zappa explained that the idea was rooted in physics:

I think of time as a spherical constant, which means that everything is happening all the time. […] They [human beings] take a linear approach to it, slice it in segments, and then hop from segment to segment to segment until they die, and to me that is a pretty inefficient way of preparing a mechanical ground base for physics. That’s one of the reasons why I think physics doesn’t work. When you have contradictory things in physics, one of the reasons they became contradictory is because the formulas are tied to a concept of time that isn’t the proper model.[7]

The pseudo-scientific implications expressed in this quotation were not always a part of Zappa’s conception of time. In a 1975 interview, Zappa discussed the idea as pertaining to life and art:

You see, the concept of dealing with things by this mechanical means that you [would] use to set your alarm clock… If you want to set your art works by it, then you’re in trouble—because then everything is going to get boring. So I’m working on a different type of a time scale.[8]

This second quotation dates from about the same time that Zappa began experimenting with xenochrony and seems suggests that the two ideas were closely related. Zappa’s conception of time may therefore be understood as a convenient justification for potentially contentious editing procedures. Although overdubbing had become common practice by the mid-1970s, combining temporally disjunct recordings was still regarded by listeners and critics as controversial. By reconfiguring the very concept of time, Zappa skirts the issue.

But even if Zappa successfully renders temporality a non-issue, xenochrony still raises questions about intentionality. Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a studio musician is called in to add a bass track to previously recorded material. While recording the new track, the bassist listens to the existing tracks and responds to the sounds in his or her headphones as though the other musicians were present. (The other musicians, for their part, would have performed their tracks knowing that a bass part would be added later.) Overdubbing, at least in cases like this, retains a degree of musical collaboration. The artistic goals and musical intentions of the various participants are more or less aligned, even though they interact in abstraction. Xenochrony, however, dispenses with intentionality altogether. For Zappa, part of the appeal is the musical product that results from combining recordings specifically of disparate temporalities, locations, and moods. The dismissal of the performer’s intentionality is an integral part of the aesthetic.

II. Intentionality

It is not my intention here to delve too deeply into issues of morality. Other discussions have shown that the ethics of manipulating recorded sound are both delicate and ambiguous. I mention these issues here because creative agency is often regarded as a source of authenticity.

In his analysis of the 1998 electronic dance music hit “Praise You,†Mark Katz discusses how Norman “Fatboy Slim†Cook takes a sample from Camille Yarbrough’s “Take Yo’ Praise†and changes it in the process.[9] In “Praise You,†Cook isolates the first verse of Yarbrough’s song and changes the tempo and timbre. Katz argues that in doing so, Cook risks potentially unethical behavior. By presenting the sample out of context and in an altered state, Cook effectively negates all of the emotional, personal, political, and sexual content and meaning of the original—a sensitive love song imbued with racial overtones related to the Civil Rights Movement. Cook therefore presents a threat to Yarbrough’s artistic agency. Katz goes on to point out—though he himself does not subscribe to this line of reasoning—that one could interpret Cook’s actions as disempowering Yarbrough or perhaps even exploiting her.

Zappa takes similar risks with xenochrony. Consider the 1979 track, “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”another xenochronous work which combines unrelated performances by bassist Patrick O’Hearn and drummer Terry Bozzio.

As with “Friendly Little Finger,†“Rubber Shirt†gives the listener the impression of performers interacting normally—each complementing and supporting the other as they explore the irregular meter. But, as Zappa describes in his liner notes on the song, “all of the sensitive, interesting interplay between the bass and drums never actually happened.â€[10] While neither Bozzio nor O’Hearn had any part in this “sensitive, interesting interplay,†their performances by themselves are highly expressive. This facet of their artistic labor, however, is obscured by the new, xenochronous setting.

As with Norman Cook’s “Praise You,†Zappa strips his sources of certain points of value. He too takes the constituent performances out of context and alters them in doing so. In many musical genres, value is closely related to a performer’s ability to interact with other musicians. When Zappa simulates interaction by xenochronously combining individual recordings, he projects new musical meaning onto performances that the original musicians did not intend. That the resulting music succeeds aesthetically does not make the practice any safer in terms of ethics.

Of course, there are also some obvious differences between “Praise You†and “Rubber Shirt,†the most important being the financial relationship between Zappa and the members of his various ensembles. O’Hearn and Bozzio were paid employees, hired to perform Zappa’s music. As their contracting employer, Zappa claimed legal ownership of any music or intellectual property produced by the members of his band. This policy seems to have been somewhat flexible in practice—O’Hearn and Bozzio are given co-writer credits for “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”but in most cases the performers of xenochronous works are not acknowledged.

Questions of acknowledgement—and related copyright issues—have plagued musical sampling from the beginning. But again, xenochrony complicates the issue. Many of the tracks on Zappa’s 1979 album Joe’s Garage,[11] for example, feature guitar solos extracted from concert performances xenochronized with studio backing tracks. All of the audible musicians are credited in the liner notes. But what of the musicians that aren’t audible? What of the ensembles that provided the original accompaniment to Zappa’s solos? By interacting with Zappa in a live setting, these musicians played a crucial role in shaping the solos that appear on Joe’s Garage. If we acknowledge the value of interactivity in musical collaboration, it would seem that credit is due to these musicians, even in their absence.

III. Authenticity

In his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Philip Auslander argues that recorded and live performances are symbiotically linked in rock culture.[12] Here, Auslander disagrees with Theodore Gracyk—who, in his 1996 book Rhythm and Noise; An Aesthetics of Rock,[13] describes these types of performance as separate media. Auslander contends that live performance validates the authenticity of recorded musicians. The nature of the recording process, he continues, raises certain doubts as to the authenticity of the musicians. When their abilities as performers are demonstrated in a live context, these questions are put to rest.[14]

According to the rock ideologies Auslander describes, studio manipulation is typically cast in a negative light. As Auslander puts it, “Listeners steeped in rock ideology are tolerant of studio manipulation only to the extent that they know or believe that the resulting sound can be reproduced on stage by the same performers.â€[15] I would venture to say that a majority of listeners are informed when it comes to the recording process. Most rock fans, in other words, are aware of the various studio tricks that go into producing the note-perfect performances heard on recordings: listening to a click track, recording multiple takes, overdubbing parts, and, more recently, digital audio processing. Except in some cases, where the technical characteristics of the music would seem to permit it, most listeners make the mental distinction that recordings are not documents of a single, perfect performance.

If Auslander is correct in his assessment of how rock ideologies view recordings with suspicion, this may, in turn, influence the terminology used to describe the process. Fans, critics, and journalists alike all speak of artists “going into the studio†to produce an album. While there, the artists are thought of as being sequestered from the world, free from outside influence—save that of a producer or, perhaps, engineer. The artists, while in the studio, are focused entirely on their creativity, free of distractions. When the artists “come out of the studio,†they have an album: the product of their creative interaction and artistic toil. Such discourse paints the studio process as having a certain purity.

Of course, this understanding derives from the various mythologies that surround rock music and its participants. That a live performance might validate the authenticity of a recording suggests that listeners are aware of the reality, but are willing to ignore it in favor of subscribing to an appealing fantasy. In Zappa’s case, however, these processes are intentionally integrated. The appeal of xenochrony, as Zappa describes it, is in achieving an effect otherwise unobtainable from live musicians:

Suppose you were a composer and you had the idea that you wanted to have […] this live on stage and get a good performance. You won’t get it. You can’t. You can ask for it, but it won’t happen. There’s only one way to hear that, and that’s to do what I did. I put two pieces of tape together.[16]

The impossibility of the virtual performance is an essential part of the aesthetic. Such a recording cannot be validated in the manner described by Auslander.

Zappa selected his sources specifically for the illusion of musical interaction they produce. Aesthetically, Zappa designs his xenochronous tracks to play the line between being feasibly performable and technically impossible. The listener becomes fully aware of the processes at play only after reading liner notes and interviews. There, Zappa reveals his manipulations and makes no attempts to cover his tracks. If anything, his descriptions of the xenochrony process are marked by an air of pride. Zappa’s listeners—who tend to be more attentive to published discussions of the music than most rock listeners—appreciate xenochrony on its own terms. For these reasons, we should view the process as a direct influence on the listener’s aesthetic experience.

In Auslander’s model, authenticity derives from live performance, characterized not only by technical ability or emotional expressivity, but also by the manner in which the performers interact with one another musically. Xenochrony, by its very nature, negates the possibility of musical interaction as a source of authenticity. Rather than the performers being the locus of authenticity, the focus is now on Zappa as recordist. Zappa replaces the traditional source of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn—as we have seen—from the art-music avant-garde of the twentieth century.

I have suggested here that Zappa’s xenochrony was influenced not only by earlier examples of phonography in pop music, but also by the philosophical theorizing of the art-music avant-garde. The picture remains incomplete, however, for it has not yet addressed the role of technology in shaping Zappa’s aesthetics.

In the late 1970s, after a series of debilitating legal battles with MGM and Warner Bros. over album distribution and the rights to master tapes, Zappa took it upon himself to start his own record company. Coinciding with the founding of Zappa Records in 1979, Zappa completed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, a fully-equipped recording studio attached to his home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. With a vast archive of studio tapes and live performance recordings, the entirety of Zappa’s work was now available to be used, reused, remixed, and manipulated. It is no coincidence that with unlimited studio and editing time at his disposal, Zappa’s experiments with xenochrony and other recording manipulations would flourish. Nearly every one of his albums from the early 1980s onward featured some degree of xenochrony.

Though far from being a direct influence, we may view Zappa’s xenochrony as foreshadowing the widespread use of digital sampling in popular music. I do not mean to suggest that Zappa should be regarded as the forefather of digital sampling as it exists now, nor even that he paved the way for it. But I do see a provocative parallel. Artists that use digital samples often find their aesthetics influenced by the results of compositional tinkering. In turn, changes in taste affect how these artists approach the business of sampling later on. I see a similar relationship between Zappa and xenochrony. In both cases, the artist interacts with his or her compositional processes, effectively setting up a feedback loop between aesthetics and means of production at hand.

All of Zappa’s musical activity can be seen as one work, constantly-evolving and perpetually unfinished. In fact, Zappa himself referred to his entire output as a single, non-chronological “project/object.â€

Individual compositions and recordings—the constituent elements of the “project/objectâ€â€”are treated not only as works in and of themselves, but as potential raw material. Though populated largely by outtakes and rejected performances, Zappa’s personal tape archive became a resource pool for further creativity—a pool to which many artists and musicians contributed. By manipulating pre-recorded material and repurposing it in such a way as to transform disparate recordings into a new, coherent entity, Zappa’s xenochrony anticipates the use of digital sampling in contemporary popular music. With contemporary sampling, however, the resource pool is greatly expanded. Sampling, in other words, renders the entirety of recorded music a vast, ever-changing, often non-intentional, unfinished work—a project/object on a global scale.

v neck beaded silk mother of the bride dress with jacket

undftd x adidas collection response mens hooded wind jacket tan camoi will be packing my go litecentury riding habitsyukon gear mens hunting insulated camo pant

adidas distancestar p谩nske be啪eck茅 top谩nky

hand drawn black ornate horoscope symbol aries. zodiac icon. royalty free hand0 primo parka jacket roxyblue sexy womens adjustable belly dance costume butterfly sequin top brathe international online fashion store

family matching mother girl swimwear bikini swimsuit set two piece bathing suit girls

pred谩m m谩lo nosen茅 lodi膷ky 1x uzavret茅 1x sand谩lky c36 cena 10 eur vr谩tane postovnehopredam lacn茅 futbalove dresy ac milan 2018 19 antonelli 31 detsk茅hra膷ka g21 detsk茅 n谩radie kufr铆k a pracovn媒 st么lnike tenisky vapormax ilava bazo拧.sk

ganni ganni sweater

elomi womens essentials bikini top from debenhams 38gg for salewalmart swimsuitsbeach please tank beach cover up beach party shirt beachambsn board shorts 34 home boardies mens swimwear stars and stripes swim trunks

makeup to match a floral dress

next floral print bodycon dress review kohls juniors floral dress floral a line dress forever 21 floral dress pink boutique flower girl dresses for babies uk strapless floral maxi dress uk

懈薪èƒæ¢°è¤‹è¤Œæ‡ˆè¤‘懈芯薪薪芯 泻芯薪褋邪谢褌懈薪è°èŠ¯èƒé‚ªè¤Ÿ 泻芯屑锌邪薪懈褟 屑芯褋泻èƒé‚ª 薪邪 锌褉芯褋锌械泻褌械 屑懈褉邪 芯褌蟹褘èƒè¤˜

dobra nocka piå¶ama dla ci臋å¶arnych i karmi膮cych best mom blue szaro niebieski zdj臋cie 1spodnie damskie 48 vintedmarynarki stroje k膮pielowe dwucz臋艣ciowep贸艂buty damskie sportowe clarks tri trail bordowe

timberland boots skeaker original usa todas las tallas bs

邪褉è¤æ‡ˆèƒ è¤æ‡ˆè¤Œ 屑è¤å¸è¤‹æ³»æ‡ˆæ¢° 泻褉芯褋褋芯èƒæ³»æ‡ˆ merrell 蟹懈屑邪 2018褋锌芯褉褌 褋泻懈写泻邪 薪邪 褌褢锌谢褘械 泻褉芯褋褋芯èƒæ³»æ‡ˆ adidas climawarm all terrainæ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ 褉è¤é”Œæ¢°è¤‰è¤‹æ³»æ‡ˆæ¢° 泻械锌泻懈 褋 锌褉褟屑褘屑 泻芯蟹褘褉褜泻芯屑 èƒ æ‡ˆè–ªè¤Œæ¢°è¤‰è–ªæ¢°è¤Œ 屑邪è°é‚ªèŸ¹æ‡ˆè–ªæ¢°è–ªèŠ¯èƒè¤˜æ¢° nike air force high black 蟹懈屑薪懈械 41 褉邪蟹屑械褉

some absolute just stole my wellies at glastonbury

ms v hokeji 2016 bl谩zniv茅 z谩morsk茅 semifin谩le prinieslo skvel媒postel rebeca cm v膷etn臎 matrace a ro拧tu hometrademu拧ketierky r.pola艅ski czerwony lico czerwony zamszzimn谩 gore tex obuv superfit 3 09093 25 crystal

nike cortez women

I would like to show appreciation to the writer for bailing me out of this crisis. Just after searching through the search engines and getting techniques that were not powerful, I assumed my life was gone. Living devoid of the answers to the problems y…

order air jordan 7 retro champagne white metallic gold black 725093 140

賮爻 丕賳 丕賱爻賴乇丞 丿丕賳 è³·è³± 兀爻賵丿 賯æ°è³·ä¹‡ä¸•ä¸¨åŒ•è³·è³´ 賳爻丕å…è³·è³´ 亘賰毓亘 毓丕賱賷 丕丨匕賷丞 賰毓亘 毓丕賱賷 噩丿丕 ä¸¨åŒ•ä¸•äº è³±å¤è³·ä¸•ä¸¿ä¸ž 丕賱胤賵賱 丕賱兀å¤è³·ä¸•äº 賵丕賱兀丨匕賷丞 ä¸•è³±è³³çˆ»ä¸•äº ä¸•è³±å™©è³²è³·è³±ä¸•è³²è³µä¸¿è³·è³±ä¸• 賮爻丕 è³·è³³ 爻賴乇丞 乇爻賲賷丞 賳丕爻亘 æ°ä¸•ä¸¨äº˜ä¸• 丕賱噩爻賲 丕賱賲賲 è³±å… 2019 賲噩賱丞 賴賷毓 亘乇 爻賵乇丞 丕賱亘賯乇丞 兀胤賵賱 爻賵乇丞 賮賷 丕賱賯乇丌賳 丕賱賰乇賷賲貙 賵賴賷 兀賵賱 爻賵乇丞 è³³å¤è³± 亘丕賱賲丿賷賳丞…

t锚nis nike air max advantage 2 masculino

nagyszer疟 kieg茅sz铆t艖k tavaszram茅regz枚ld g茅pi k枚t茅s疟 fels艖m谩gneses kark枚t艖 insportline amila insportlineunique white strandruha bw 974 origami m茅ret egy m茅ret

rihanna was serving looks in this revealing dress on new years eve

orange men polo tshirt buy orange men polo tshirt online in indianike air pivot v3 t shirt white black beiwhite cat embroidery long sleeve chic shirt womens shirts blousespandora brown leather bracelets

adidas originals jakke stré…¶mpebukser og t skjé…¶rt til salgs

tuxedo blazer in saint laurent grain de poudre with passementerie buttonslong a line beach wedding dress davids bridal collectionyves saint laurent authentic classic sac de jour nano in embossedoriginal real solid 925 sterling silver necklace fashion v…

completi da calcio squadre

camicia camicetta di pizzo sexy senza maniche halter neck donne camicette di estate della stampa delpromozione cd 3 al 20 di scontouomo intimissimi per avere stile e comfort sempreme ru zip off pant women damebukser turbulence

nike mercurial vapor x fg cr7 barn

evoc hip pack pro 3l carbon grey chili redg16 tropp til turnering i polen norges fotballforbundscott 450 tré…¶ye sort hvit toppmodellen blant mx tré…¶yer motorspeed assté…¶vler alt i sté…¶vler til herre i topkvalitet til lave priser

custom i am a simple woman crewneck sweatshirt by wizarts artistshot

inexpensive strapless neckline a line tea length beach wedding dresses with sequined bustariel little mermaid girls personalized birthday tutu outfit and bow on headband ages 1 6off shoulder wedding dress ivory pearls tulle maxi tullebadgley mischka go…

lion king shirt on the hunt

latest jimmy choo vicky 30 light mocha pumps for women sale onlineburlap drawstring bag good for door gift favorsparker convertible backpack 16summer sales are here get this deal on womens ted baker london

wonder price prada prada nylon orange robo tote bag tote bag

womens white alex oversized chunky sneakers rubber sole trainers new shoes sizeadidas st windbreaker yellowcolumbia mens plus iii omni cold weather bootthe sole of the blue nike mercurial x 2015 2016 indoor

pandora pendant charm locket of dazzling necklace multi color

item 2 swarovski crystal botanic round stud earrings set 5071152 swarovski crystal botanic round stud earrings set 5071152sterling silver teardrop pendant lake shore funeral homepaul magen contemporary hand textured hoop earrings made in sterling silve…

hougood enfants robe princesse robe de soir茅e robe formelle robe d茅t茅 rose fleur papillon f茅e d茅guisement age 2 13 ans

calcinha baixa ametista avon storecanga redonda indiana mandala praia piscina campo yoga r 69conhe莽a os 12 vestidos mais caros que j谩 passaram pelo tapete vermelhodafiti vestidos curtos vestidos para meninas festa rosa claro em

air max 90

Thank you for all of the efforts on this site. My niece take interest in managing investigations and it is easy to see why. A lot of people know all regarding the lively means you deliver important solutions by means of your web site and as well as boo…

search results. hot

锌褉芯写邪屑 屑械斜械谢褜 写谢褟 写械褌褋泻芯泄 芯斜褗褟èƒè°¢æ¢°è–ªæ‡ˆè¤Ÿ 薪邪屑芯写薪褘械 å¸æ¢°è–ªè¤‹æ³»æ‡ˆæ¢° 褌褢锌谢褘泄 è°è°¢é‚ªå±‘è¤è¤‰è–ªè¤˜æ³„ 褎懈褉屑械薪薪褘泄 褋锌芯褉褌懈èƒè–ªè¤˜æ³„ 泻芯褋褌褞屑 褌è¤è¤‰è¤‘懈褟victorias secret 褌褉è¤è¤‹æ‡ˆæ³»æ‡ˆ very sexy æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ èƒ æ³»è¤‰é‚ªè¤‹è–ªèŠ¯å†™é‚ªè¤‰æ¢°å†™å¸æ¢°è°è°æ‡ˆè–ªè¤‹è¤˜ 锌芯写褉芯褋褌泻芯èƒè¤˜æ¢° ascxe 芯锌褌芯屑 627 3

abiti cerimonia plus size acquistare online. abiti cerimonia plus size acquistare online

battercake abiti donna eleganti da cerimonia vestiti corti pizzo in chiffon manica casuale donne lunga rotondocaricamento dellimmagine in corso boxer uomo diesel rosso con stampa vintagepianura iconic gonna balze calabrofashionpantaloni leopardati neon…

bennett camo dress

nosi膷 motoriek hakr crossmodern茅 d谩mske hned茅 lodi膷ky na klinemal by naozaj ka啪d媒 mu啪 vlastni钮 p谩r chelsea bootsorto d谩mska obuv 1561

bruker egne klå¿™r for æ°“ kontroll

褉邪褋锌褉芯写邪å¸é‚ª 屑è¤å¸è¤‹æ³»æ‡ˆæ¢° æ³»è¤è¤‰è¤Œæ³»æ‡ˆ 懈 锌邪褉泻懈 èƒ æ‡ˆè–ªè¤Œæ¢°è¤‰è–ªæ¢°è¤Œ 屑邪è°é‚ªèŸ¹æ‡ˆè–ªæ¢° 褋芯 褋泻懈写泻芯泄褞斜泻邪 èƒ è¤‹é”ŒèŠ¯è¤‰è¤Œæ‡ˆèƒè–ªèŠ¯å±‘ 褋褌懈谢械 . å¸æ¢°è–ªè¤‹æ³»é‚ªè¤Ÿ 芯写械å¸å†™é‚ª. 懈薪褌械褉薪械褌 屑邪è°é‚ªèŸ¹æ‡ˆè–ªè¤‹æ‡ˆè–ªæ‡ˆæ³„ æ³»è¤é”Œé‚ªè°¢è¤œè–ªæ‡ˆæ³» 褋 斜芯谢褜褕懈屑 锌è¤è¤• 邪锌 æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ èƒ å±‘èŠ¯è¤‹æ³»èƒæ¢° 薪邪 avitoè°å†™æ¢° èƒ å±‘èŠ¯è¤‹æ³»èƒæ¢° 蟹邪泻邪蟹邪褌褜 è¤è¤‹è°¢è¤è°è¤ 写芯褋褌邪èƒæ³»é‚ª èƒèŠ¯å†™è¤˜ èƒ èŠ¯è¤Žæ‡ˆè¤‹

weekend re cap southern curls pearls

oliver peoples elerson glasses 305 buy online mobile friendlyshop tory burch ty9028 510 13 havana rectangular sunglasses 56 18michael kors rachel aviator sunglasses in gunmetal amazon.co.uk clothingwolfgang sunglasses granite horn

camisa retro brasil 1958 sele莽茫o brasileira alusiva copa 58. carregando zoom

in extenso pantalon gar莽onsac bandouli猫re chicmonoprix robe housse imprim茅esweat gar莽on zipp茅 doubl茅 marine grise orange clair vert 7 vertbaudet enfant

蟿蟽伪谓蟿伪 èŸ¿ä¼ªè ‚è €æœªèŸ»æ…°æ¸æ…°è € lycsac one markie lollipops

褋è¤å±‘泻邪 薪邪 锌芯褟褋 æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ èƒ æ‡ˆè–ªè¤Œæ¢°è¤‰è–ªæ¢°è¤Œ 屑邪è°é‚ªèŸ¹æ‡ˆè–ªæ¢° 薪邪 褟褉屑邪褉泻械 å±‘é‚ªè¤‹è¤Œæ¢°è¤‰èŠ¯èƒ è¤‹èƒè–ªè¤è¤Œè¤‰æ¢°è–ªè–ªæ¢°æ³„ 褋褌芯褉芯薪械 褋è¤å±‘泻懈. 褔邪褋褌芯 锌褉懈谢邪è°é‚ªæ¢°è¤Œè¤‹è¤Ÿ 锌谢邪褋褌懈泻芯èƒé‚ªè¤Ÿ 泻邪褉褌邪 . 褋械褉褌懈褎懈褑懈褉芯èƒé‚ªè–ªè–ªè¤˜è¤ æ–œè¤è¤Œæ‡ˆæ³»èŠ¯èƒ 锌褉懈3 褉褞泻蟹邪泻 gopack 屑芯谢芯写械å¸è–ªè¤˜æ³„ 写谢褟 褋褌è¤å†™æ¢°è–ªè¤ŒèŠ¯èƒ 锌褉芯写邪å¸é‚ªæ³»èŠ¯å¸é‚ªè–ªè¤˜æ¢° 褋è¤å±‘泻懈 diesel

funda contra agua sumergible universal iphone galaxy note. cargando zoom

alexander mcqueen tiger and skull jersey t shirt t shirtsmakeup bag kit clear. shop this collectionshop all sonia kashuklee jeans jeans 90s rider salinalily pulitzer pink one piece floral print bathing suit size 10 nwt

kwmobile funda para samsung galaxy tab s2 8.0 electrè´¸nica

light blue cable knit cardigan sal kidsraw hem skinny jeans black ombre nimeselegant and stylish swim cover ups or sexy see through loungeweark swiss mens black lily white classic vn se sneakers athletic shoes vipbrands

25 petites robes de plage femme actuelle le mag

moletom c capuz e bolso queen camerockcamisa s茫o paulo adidas 2018 nene 10 jogo patroc铆nios g r 370agasalho puma palmeiras 2019 masculino verdepasta masculina de couro leg铆timo lc floater marrom

ivy purse clutch dark chocolate

gyalia iliou 胃èŽé蔚蟼 çº¬è €ä¼ªä½å–‚è ‹è°“gts 喂蟽慰胃蔚蟻æ¸å–‚éæ…° éæ…°ä½ä¼ªè°“ water motionç• çº¬è €è°“ä¼ªå§”é伪 æ¸è”šèŸ¿ç»´ 蟿伪 40维蟽蟺蟻慰 èŸºæ…°è €ç»´ æ¸ä¼ªéèŸ»è ‰ è è ˆèŸ»è”šæ¸ä¼ª éèŸ»æ…°è €ä¼ªå‘³è‹‡ æ¸è”š æ¸è”šçº¬ç»´ä½æ…° 蟽é委蟽喂æ¸æ…° é伪喂 å‘³è ‹è°“ç•

borlas ante puntiagudas tacè´¸n alto botas finas con mè°©s gruesas zapatos de mujer

é—虫棩é§æ´ªâ‚¬?éŠ‰î…œå…‚éŠˆèˆ¬å„»éŠ‰ç‚½å„ŸéŠ‰ç¬ºå£ éŠˆî‚å„ éŠˆæž«å„³éŠ‰?l æµ æ ¥åŸéŠˆã‚ƒå¤éˆ?濂虫€Ñå„ éŠˆÂ°å„銈枫儳銉炽伄é‚囬潚濂冲é肩磱娲媔nstagram posts姘寸潃 éŠ‰å ›å„¸éŠ‰ç‚½å’姘寸潃 銉儑銈c兗銈?2017 é„?澶?娴?銉椼兗銉?銈裤å†éŠ‰?銉å–銉炽å£éŠ‰å¿‹å„¹éŠˆï¸ºå…銉炽å„銉î‚å£éŠˆç‚½å£éŠ‰æ¤¼å„¸ 銉曘儵銉冦å˜éŠ‰ä½µå‹éŠ‰å†¦å—銇儶銉溿兂銇屽彲鎰涖亜

elegant bridal wedding shoes nude lace shoes for wedding bridesmaids prom party evening shoes pumps on luulla

2 6 ans jeans b茅b茅 gar莽on denim doux jeans pour enfants pantalon pour enfants pantalonpyjama b茅b茅 velours 2 pi猫ces avec pieds prix r茅duit. ensemble b茅b茅 fille t shirt pantalon r锚veusefemme maillot bain 2pi猫ces tankini bikini shorts tankini ensembleenfa…

eyelash serum growth organic lash booster serum eyelash

camisa feminina arrow rosat锚nis asics gel nimbus 20 feminino 36 azulsapato couro masculino amsterdam alth rafarillo azul bic. carregando zoomcamisa chapecoense goleiro no

saia god锚 curta cap茅zio danzarin a loja que veste sua dan莽a

damen web hose langwoman by tchibo second hand online shop10 er pack head boxershorts schwarz size xl herren unterhose w盲scheheiko maas 眉ber die gro脽e koalition bei spd ist

furgora casual the official kangol store

tmnt group attack official mens t shirt 鈥?urban speciessunset stripe crewforever 21 girls ringer t shirt dress from forever 21funny christmas baby clothes accessories cafepress

nike air zoom vomero 13 test superato a pieni

em oferta barato bota coturno adventure feminina r 99sapato social pegada verniz marrom compre agorasapat锚nis masculino slip on 8509 marinho preto 37ballet acessorios casaquinho rosa

prix de gros vendre t chemises d茅t茅 lin hommes ensemble 脿 manches courtes mode de bonne

bota azimute brasil adventure pedra oliva na j cal莽adosbon茅 trucker todo branco brasil copa no elo7t锚nis menina puma turin ii ac branco rosapromo莽茫o camisas masculinas

kim kardashian cover up kim kardashian swimwear looks stylebistro

trendy classic tweed purple fedora hat plus size clubwearsaint laurent classic 6 sunglassesvintage ladies pocket watch broochysl size 5 womens leather boots

bininbox damen bodycon wolle strickkleid blumenmuster print rollkragen langarm pullover sweatkleid longshirt

maybelline new york colossal volum express mascara cat eyes glam black 9.5ml. descriptionsilicone eye lash extension shields eyelash lifting curlersfenty island bling 2 1 liquid eyemagnetic eyelash extensions false eyelashes dealsboutiq

roupas de inverno o que n茫o pode faltar no seu guarda roupa da esta莽茫o

prescription sunglasses sneaking duckdolce gabbana spring 2020 menswear collection voguemens aluminum hd polarized sunglasses driving sports mirrored glasses eyewearcalabria viv kids 117 designer eyeglasses in wine demo

銈汇兗銉?銈枫儯銉炽åªéŠ‰è™«æ´¿ç»±æ¤¼å„”éŠ‰îƒ¾å£ éŠ‰î…œå…‚éŠˆ?銉炪å”銈蜂笀銉兂銉斻兗銈?amaca

outfits men boots comfortable quality high top shoes men new casual shoeshot pink floral leather heeled sandals manolo blahnik ranca floral print strappy sandal pinkmultihot wave slippers for ladiessam edelman womens crisscross leather slides black siz…

jasmine black label blue mother of the bride dress

mokasyny na podeszwie w nowej ods艂onie firmy ry艂ko.wykonane ze skè´¸ry welurowej o specjalnejbuty zimowe m臋skie czarne lee cooper skè´¸rzane wi膮zane m艂odzieå¶owe wszpilki cz贸艂enka pastelowe syrena super 38 latoarchiwalne sprzedam kozaki rozmiar 45

canada goose trillium fur trim parka

haglæžšfs vina 30 blue ink steel sky m lkjé…¶p skogstad mote til herre pæ°“ nettkæžšp viking vinderen gore tex sko navy limecasall iconic long sleeve 901 black

UNDUN Sneakers Nero pelle contiene parti non tessili di origine animale punta tonda tinta unita 11593927LS

Chevignon CAMISA VAQUERA – AZUL 100% algodón Corte recto Cuello con solapas 2593859

c4 classic belt unisex plastik g眉rtel mit wechselbarer schnalle

g403 wireless priceeyelash extensions for longereyelure no.143 exaggerate false lashes. perfect for glam box depopcatrice cosmetics lash brow designer shaping conditioning gel

girls tie dye crewneck t shirt

supreme apps on google playsnidel 銈广儕銈ゃ儑銉?fila銈广åŠéŠˆÑå„éŠ‰å ›å„»éŠ‰ç‚½å„ŸéŠ‰ç¬ºå£ 19é„ュ闈掑北娲嬫湇é—逛环 闈掑北娲嬫湇鎬åºç®žé锋惌閰嶅浘é—?娣樺疂缃戦潚çžè¾¨ç£±éˆå¶…ã‡é®ä½½î‡©æ¿‚å® î—Šç€›ï¸½ç‰Ž 姘寸潃 銉兂銉斻兗銈?/a>

no7 silk crop jacket black white

èŸºè … 谓伪 è 慰蟻 蟽蔚喂 蟿慰 èŸºæ…°è €é æ¸å–‚蟽慰 èŸ½æ…°è € è ‚è …èŸ» 纬蟻伪尾 蟿伪zaino eastpak 3 taschedescubra como cortar o cabelo em vvintage and musthaves. fendi logo canvas leather bag

body decote tran莽ado em suplex moda 2017 for her clothes

nike crew fleece team club 19 sweatshirt herren grausommer strickjacke mop marc opolo grobstrick lurex rosa l xl 42 44g眉nstig 8th sign striped culotte jumpsuits damen schwarz wei脽 salemarc opolo damen taschen g眉nstig online kaufen