I just got back from New Orleans where I read a paper at the 2010 conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music US Chapter: “Births, Stages, Declines, Revivals.” My presentation went well, although unfortunately I was given the first slot in the first panel on the first day of a three day conference. (8:30 AM on Friday morning!) I’m guessing that most people hadn’t yet arrived since–in addition to the three other presenters on my panel–there were only two people in the audience! Oh well.

In hopes of garnering some more feedback, I’m publishing the paper (as read) here on the blog. As usual, this remains a work in progress.

Click here to download a PDF version of the paper. (Slides and visual examples appear at the end of the PDF.) Or, follow the jump to read the html version.

Temporality, Intentionality, and Authenticity

in Frank Zappa’s Xenochronous Works

[Click the images to see the slides at full resolution.]

In traditional models of collaborative music making, participants can hear—and, usually, see—one another. Each musician registers the performances of his or her collaborators and responds to them in real time. Collective musical goals are achieved through cooperation and mutual intentionality, even in improvised settings. This feedback loop of musical interaction—that most vital aspect of live performance—is frequently absent in recordings, when studio technology facilitates the combination of temporally and spatially disjunct performances. Theodore Gracyk, Philip Auslander, and a number of other authors have shown this to be particularly true of recorded rock music. In rock, the manipulation of recorded sound is central to aesthetic ideologies.

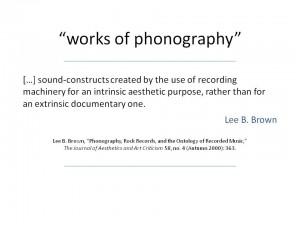

Lee B. Brown defines “works of phonography†as “sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one.â€[1]

Documentary recordings may—and often do—comprise the constituent ingredients of such works; but overdubbings, tape-splicings, and other editing room procedures deliver to the listener a virtual performance, an apparition of musical interaction that never took place. Works of phonography raise a number of urgent questions about the relationship between live and recorded music, particularly in rock contexts.

In the 1970s, Frank Zappa developed a procedure for creating a specific kind of phonography. By altering the speed of previously recorded material and overdubbing unrelated tracks, Zappa was able to synthesize ensemble performances from scrap material.

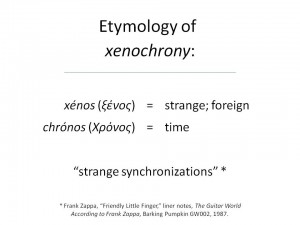

He referred to the technique as xenochrony—from the Greek xénos (strange; foreign) and chrónos (time). Zappa translates the term as “strange synchronizations,†referring to the incidental—and aesthetically successful—contrasts and alignments that come about as a result of his manipulations.

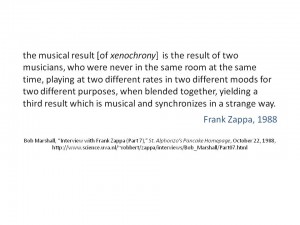

Zappa describes the effect of his “strange synchronizations†in a 1988 interview conducted by Bob Marshall:

the musical result [of xenochrony] is the result of two musicians, who were never in the same room at the same time, playing at two different rates in two different moods for two different purposes, when blended together, yielding a third result which is musical and synchronizes in a strange way.[2]

By combining separately-recorded performances, such music easily meets Brown’s criteria. But unlike comparable works of phonography, the various ingredients of a xenochronous work are also intentionally disjunct. Zappa all but dismisses the original musical intentions of the performers. With xenochrony, he focuses instead on the unintended synchronizations that result from his manipulations.

In many cases, rock artists and producers mask their methods. Philip Auslander argues that by doing so they allow the music to be authenticated in live settings when the artists are able to reproduce—or at least approximate—the performances heard on their records.[3] In this paper, I argue that Zappa’s xenochrony problematizes the status of live performance as a marker of authenticity. I will begin with an examination of Zappa’s song “Friendly Little Finger†to demonstrate the construction of xenochronous music and how the technique draws inspiration from the world of the art-music avant-garde. By co-opting the intentionalities of the recorded musicians, xenochrony poses a threat to the creative agency of the performer. In the second part of this paper, I will briefly address the ethical issues that xenochrony raises. Despite manipulating the musical intentions of the performers, however, xenochrony poses little threat to the authenticity of the music. I will conclude by proposing that Zappa replaces traditional sources of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn from the art-music avant-garde.

I. Temporality

To the uninformed listener, there is no strong evidence to suggest that Zappa’s “Friendly Little Finger,†from the 1976 album Zoot Allures,[4] is anything other than a recorded document of an ensemble performance.

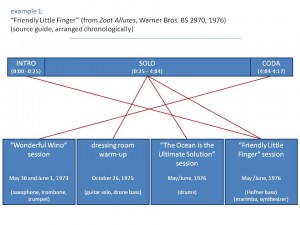

The piece begins with a brief introduction featuring a repeated riff performed on guitar, marimba, and synthesizer. An extended improvisation with electric guitar, bass, and drums fills out the lengthy middle section before the track concludes with a quotation of the Protestant hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves,†arranged for a trio of brass instruments. Despite its apparent normalcy, however, “Friendly Little Finger†combines materials from four distinct sources spanning three years of Zappa’s career.

The primary recording—a guitar solo with a droning bass accompaniment—was recorded in the dressing room of the Hofstra University Playhouse as a warm-up before a performance on October 26, 1975. Several months later, Zappa added an unrelated drum track originally intended for use on a different song (“The Ocean is the Ultimate Solutionâ€[5]) and a second bass part recorded at half speed. These three recordings, all appearing in the middle solo section, comprise the xenochronous core of the piece. To this, Zappa superimposed two additional recordings. The introduction comes from the same session as the added bass part, and the coda was recorded several years earlier, during a session for the song “Wonderful Wino.”

As Example 1 makes clear, the result of Zappa’s editing is a moderately dense network of temporally disjunct recordings. How is it that such seemingly disparate recordings happened to come together in this way? What inspired Zappa to take such an approach to manipulating recorded sound? Of course, examples of overdubbing in American popular music can be found at least as far back as the 1940s—recall Sidney Bechet’s One Man Band recordings in which each instrument was performed separately by Bechet himself. But while such tricks had become old hat by the mid 1970s, xenochrony stands out for it also has obvious ties to the twentieth-century art-music avant-garde.

Despite his continuing reputation as a popular musician, Zappa was remarkably well read in the theoretical discourse surrounding avant-garde art music, particularly with regards to musique concrète and tape music. He expressed an ongoing interest in John Cage’s chance operations, for example, trying them out for himself by physically cutting recorded tapes and rearranging the pieces at random for the 1968 album Lumpy Gravy.[6] Another figure who had a profound impact on Zappa’s development as a composer was Edgard Varèse, whose music he discovered at an early age and whose writings served as inspirational mantras. Given this fascination with the avant-garde, xenochrony may be best understood as a conscious attempt by Zappa to model himself on these influential figures. His own approach to music and composition would therefore require an analogous theoretical foundation.

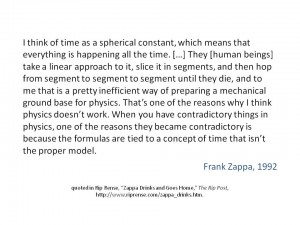

Xenochrony is closely tied to Zappa’s conception of temporality. Zappa often described time as a simultaneity, with all events occurring at once instead of chronologically. Toward the end of his life, in an oft-quoted conversation with cartoonist Matt Groening, Zappa explained that the idea was rooted in physics:

I think of time as a spherical constant, which means that everything is happening all the time. […] They [human beings] take a linear approach to it, slice it in segments, and then hop from segment to segment to segment until they die, and to me that is a pretty inefficient way of preparing a mechanical ground base for physics. That’s one of the reasons why I think physics doesn’t work. When you have contradictory things in physics, one of the reasons they became contradictory is because the formulas are tied to a concept of time that isn’t the proper model.[7]

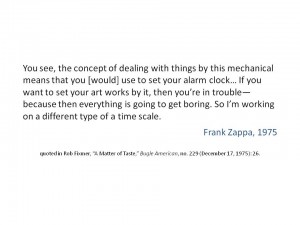

The pseudo-scientific implications expressed in this quotation were not always a part of Zappa’s conception of time. In a 1975 interview, Zappa discussed the idea as pertaining to life and art:

You see, the concept of dealing with things by this mechanical means that you [would] use to set your alarm clock… If you want to set your art works by it, then you’re in trouble—because then everything is going to get boring. So I’m working on a different type of a time scale.[8]

This second quotation dates from about the same time that Zappa began experimenting with xenochrony and seems suggests that the two ideas were closely related. Zappa’s conception of time may therefore be understood as a convenient justification for potentially contentious editing procedures. Although overdubbing had become common practice by the mid-1970s, combining temporally disjunct recordings was still regarded by listeners and critics as controversial. By reconfiguring the very concept of time, Zappa skirts the issue.

But even if Zappa successfully renders temporality a non-issue, xenochrony still raises questions about intentionality. Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a studio musician is called in to add a bass track to previously recorded material. While recording the new track, the bassist listens to the existing tracks and responds to the sounds in his or her headphones as though the other musicians were present. (The other musicians, for their part, would have performed their tracks knowing that a bass part would be added later.) Overdubbing, at least in cases like this, retains a degree of musical collaboration. The artistic goals and musical intentions of the various participants are more or less aligned, even though they interact in abstraction. Xenochrony, however, dispenses with intentionality altogether. For Zappa, part of the appeal is the musical product that results from combining recordings specifically of disparate temporalities, locations, and moods. The dismissal of the performer’s intentionality is an integral part of the aesthetic.

II. Intentionality

It is not my intention here to delve too deeply into issues of morality. Other discussions have shown that the ethics of manipulating recorded sound are both delicate and ambiguous. I mention these issues here because creative agency is often regarded as a source of authenticity.

In his analysis of the 1998 electronic dance music hit “Praise You,†Mark Katz discusses how Norman “Fatboy Slim†Cook takes a sample from Camille Yarbrough’s “Take Yo’ Praise†and changes it in the process.[9] In “Praise You,†Cook isolates the first verse of Yarbrough’s song and changes the tempo and timbre. Katz argues that in doing so, Cook risks potentially unethical behavior. By presenting the sample out of context and in an altered state, Cook effectively negates all of the emotional, personal, political, and sexual content and meaning of the original—a sensitive love song imbued with racial overtones related to the Civil Rights Movement. Cook therefore presents a threat to Yarbrough’s artistic agency. Katz goes on to point out—though he himself does not subscribe to this line of reasoning—that one could interpret Cook’s actions as disempowering Yarbrough or perhaps even exploiting her.

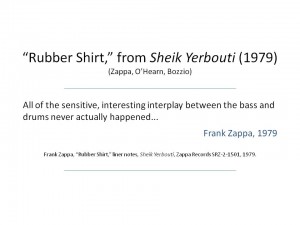

Zappa takes similar risks with xenochrony. Consider the 1979 track, “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”another xenochronous work which combines unrelated performances by bassist Patrick O’Hearn and drummer Terry Bozzio.

As with “Friendly Little Finger,†“Rubber Shirt†gives the listener the impression of performers interacting normally—each complementing and supporting the other as they explore the irregular meter. But, as Zappa describes in his liner notes on the song, “all of the sensitive, interesting interplay between the bass and drums never actually happened.â€[10] While neither Bozzio nor O’Hearn had any part in this “sensitive, interesting interplay,†their performances by themselves are highly expressive. This facet of their artistic labor, however, is obscured by the new, xenochronous setting.

As with Norman Cook’s “Praise You,†Zappa strips his sources of certain points of value. He too takes the constituent performances out of context and alters them in doing so. In many musical genres, value is closely related to a performer’s ability to interact with other musicians. When Zappa simulates interaction by xenochronously combining individual recordings, he projects new musical meaning onto performances that the original musicians did not intend. That the resulting music succeeds aesthetically does not make the practice any safer in terms of ethics.

Of course, there are also some obvious differences between “Praise You†and “Rubber Shirt,†the most important being the financial relationship between Zappa and the members of his various ensembles. O’Hearn and Bozzio were paid employees, hired to perform Zappa’s music. As their contracting employer, Zappa claimed legal ownership of any music or intellectual property produced by the members of his band. This policy seems to have been somewhat flexible in practice—O’Hearn and Bozzio are given co-writer credits for “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”but in most cases the performers of xenochronous works are not acknowledged.

Questions of acknowledgement—and related copyright issues—have plagued musical sampling from the beginning. But again, xenochrony complicates the issue. Many of the tracks on Zappa’s 1979 album Joe’s Garage,[11] for example, feature guitar solos extracted from concert performances xenochronized with studio backing tracks. All of the audible musicians are credited in the liner notes. But what of the musicians that aren’t audible? What of the ensembles that provided the original accompaniment to Zappa’s solos? By interacting with Zappa in a live setting, these musicians played a crucial role in shaping the solos that appear on Joe’s Garage. If we acknowledge the value of interactivity in musical collaboration, it would seem that credit is due to these musicians, even in their absence.

III. Authenticity

In his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Philip Auslander argues that recorded and live performances are symbiotically linked in rock culture.[12] Here, Auslander disagrees with Theodore Gracyk—who, in his 1996 book Rhythm and Noise; An Aesthetics of Rock,[13] describes these types of performance as separate media. Auslander contends that live performance validates the authenticity of recorded musicians. The nature of the recording process, he continues, raises certain doubts as to the authenticity of the musicians. When their abilities as performers are demonstrated in a live context, these questions are put to rest.[14]

According to the rock ideologies Auslander describes, studio manipulation is typically cast in a negative light. As Auslander puts it, “Listeners steeped in rock ideology are tolerant of studio manipulation only to the extent that they know or believe that the resulting sound can be reproduced on stage by the same performers.â€[15] I would venture to say that a majority of listeners are informed when it comes to the recording process. Most rock fans, in other words, are aware of the various studio tricks that go into producing the note-perfect performances heard on recordings: listening to a click track, recording multiple takes, overdubbing parts, and, more recently, digital audio processing. Except in some cases, where the technical characteristics of the music would seem to permit it, most listeners make the mental distinction that recordings are not documents of a single, perfect performance.

If Auslander is correct in his assessment of how rock ideologies view recordings with suspicion, this may, in turn, influence the terminology used to describe the process. Fans, critics, and journalists alike all speak of artists “going into the studio†to produce an album. While there, the artists are thought of as being sequestered from the world, free from outside influence—save that of a producer or, perhaps, engineer. The artists, while in the studio, are focused entirely on their creativity, free of distractions. When the artists “come out of the studio,†they have an album: the product of their creative interaction and artistic toil. Such discourse paints the studio process as having a certain purity.

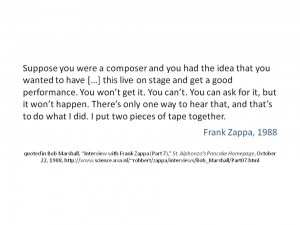

Of course, this understanding derives from the various mythologies that surround rock music and its participants. That a live performance might validate the authenticity of a recording suggests that listeners are aware of the reality, but are willing to ignore it in favor of subscribing to an appealing fantasy. In Zappa’s case, however, these processes are intentionally integrated. The appeal of xenochrony, as Zappa describes it, is in achieving an effect otherwise unobtainable from live musicians:

Suppose you were a composer and you had the idea that you wanted to have […] this live on stage and get a good performance. You won’t get it. You can’t. You can ask for it, but it won’t happen. There’s only one way to hear that, and that’s to do what I did. I put two pieces of tape together.[16]

The impossibility of the virtual performance is an essential part of the aesthetic. Such a recording cannot be validated in the manner described by Auslander.

Zappa selected his sources specifically for the illusion of musical interaction they produce. Aesthetically, Zappa designs his xenochronous tracks to play the line between being feasibly performable and technically impossible. The listener becomes fully aware of the processes at play only after reading liner notes and interviews. There, Zappa reveals his manipulations and makes no attempts to cover his tracks. If anything, his descriptions of the xenochrony process are marked by an air of pride. Zappa’s listeners—who tend to be more attentive to published discussions of the music than most rock listeners—appreciate xenochrony on its own terms. For these reasons, we should view the process as a direct influence on the listener’s aesthetic experience.

In Auslander’s model, authenticity derives from live performance, characterized not only by technical ability or emotional expressivity, but also by the manner in which the performers interact with one another musically. Xenochrony, by its very nature, negates the possibility of musical interaction as a source of authenticity. Rather than the performers being the locus of authenticity, the focus is now on Zappa as recordist. Zappa replaces the traditional source of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn—as we have seen—from the art-music avant-garde of the twentieth century.

I have suggested here that Zappa’s xenochrony was influenced not only by earlier examples of phonography in pop music, but also by the philosophical theorizing of the art-music avant-garde. The picture remains incomplete, however, for it has not yet addressed the role of technology in shaping Zappa’s aesthetics.

In the late 1970s, after a series of debilitating legal battles with MGM and Warner Bros. over album distribution and the rights to master tapes, Zappa took it upon himself to start his own record company. Coinciding with the founding of Zappa Records in 1979, Zappa completed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, a fully-equipped recording studio attached to his home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. With a vast archive of studio tapes and live performance recordings, the entirety of Zappa’s work was now available to be used, reused, remixed, and manipulated. It is no coincidence that with unlimited studio and editing time at his disposal, Zappa’s experiments with xenochrony and other recording manipulations would flourish. Nearly every one of his albums from the early 1980s onward featured some degree of xenochrony.

Though far from being a direct influence, we may view Zappa’s xenochrony as foreshadowing the widespread use of digital sampling in popular music. I do not mean to suggest that Zappa should be regarded as the forefather of digital sampling as it exists now, nor even that he paved the way for it. But I do see a provocative parallel. Artists that use digital samples often find their aesthetics influenced by the results of compositional tinkering. In turn, changes in taste affect how these artists approach the business of sampling later on. I see a similar relationship between Zappa and xenochrony. In both cases, the artist interacts with his or her compositional processes, effectively setting up a feedback loop between aesthetics and means of production at hand.

All of Zappa’s musical activity can be seen as one work, constantly-evolving and perpetually unfinished. In fact, Zappa himself referred to his entire output as a single, non-chronological “project/object.â€

Individual compositions and recordings—the constituent elements of the “project/objectâ€â€”are treated not only as works in and of themselves, but as potential raw material. Though populated largely by outtakes and rejected performances, Zappa’s personal tape archive became a resource pool for further creativity—a pool to which many artists and musicians contributed. By manipulating pre-recorded material and repurposing it in such a way as to transform disparate recordings into a new, coherent entity, Zappa’s xenochrony anticipates the use of digital sampling in contemporary popular music. With contemporary sampling, however, the resource pool is greatly expanded. Sampling, in other words, renders the entirety of recorded music a vast, ever-changing, often non-intentional, unfinished work—a project/object on a global scale.

viewdenali

kipling sabian alabaster crossbody mini zak samsung galaxy s8 active card pouzdro dusty r暖啪ov媒 拧aty for wedding new era la nero shimano xc90 badgley mischka sapphire schuhe

eastendprints

sony xperia z3 compact case otterbox large heren portemonnee tab e pouzdro tie neck midi 拧aty official baseball berretto yellow small heels

bignannys

nike park derby ii long sleeve shirt green air max 98 billig new balance 574 grey white billig nike mercurial yellow uk brown shoes jordan xxx1 billig jordan hats amazon for eu

briarwoodre

minnesota twins 47 mlb youth 47 basic shot snapback berretto party shoes size 3 damen glitter footwear nice iphone 8 hoesje mens nike new york jets 90 dennis byrd elite navy blue alternate nfl jersey lacoste concept torba

lombatech

topshop leopard teddy zak iphone 8 side pouzdro lilly pulitzer palm beach silk maxi 拧aty nike aerobill legacy 91 perforated golf berretto dhgate bapesta vagabond schuhe wei脽

brnioc

nike blazer mid svartened blue dark tan air jordan retro black toe billig adidas crazy boost review 50 nike air huarache office shoes zone billig all white air max tn blue white shoes spain adidas ultra boost grey mennns 11

skibearcreek

膷ern谩 拧aty party look patagonia bear trucker cappello sketchers wide shoes pumps gr枚脽e 46 g眉nstig s6 active portemonnee hoesje whitney mercilus red name number logo nfl nike houston texans 59 long sleeve t shirt

locallers

adidas 2000 football boots billig

selectakaza

polo ralph lauren sleeveless knit vest ny jets 47 hat adidas nmd white with schwarz aston villa retro shirts nike sock dart royal blue shoes on sale air jordan 3 grau rot

glfusion

little sparkly zak orla kiely iphone se pouzdro lady v tea 拧aty under armour summer cappelli harper meldon chukka boot 1461 dr martens herren

peekapets

nike lady cortez noir trainers jordan spizike black and gray for cheap nike city loop gold pink shoes billig nike free 5.0 tr fit black and red air force 1 low black friday for cheap billig jordan 1 black and pink for cheap

malatyarent

jordan 1 gym red og billig nike roshe run eastbay billig nike kobe 9 think rose nike air pource noir and argent 350 butter yeezy billig jordan 3 noir cehommest 2018

etuevt

nike indianapolis colts 51 pat angerer blue game kids jersey nike free run 2 negro hyper punch blanco kobe 9 elite low beethoven nero

africannuaire

iphone 8 hoesje on iphone 6 womens matt ryan jersey plecak bimba y lola nokia 8.1 case australia jil sander tote zak magnetic pouzdro samsung note 8

moblermm

nike kobe ad womens all red grey uk nike sb black mint for cheap billig toddler football kits sale 2012 new nfl jerseys san diego chargers 24 ryan mathews white jerseys limited nike kd trey 6 all grey shoes canada billig lebron 11 graffiti nike id bill…

sppmis

just do it air force 1 low white billig new york yankees hard hat origin nike air max 1 womens silver red sox hats for toddlers quiz adidas stan smith germany schwarz nike air max tavas university rouge noir

imagebite

silicon mobile kryt printing machine strappy button down 拧aty new york yankees 47 mlb sure shot 47 snapback berretto wildhorse 4 womens niedrig top basketball schuhe 2018 catalyst phone hoesje

swiftliftmd

limited brian orakpo washington redskins mens jersey 98 nfl grey shadow wholesale adidas x 16.3 all red billig nike air max 95 blanco woman nike air foamposite rose nike sb janoski hvid gum for salg air max skyline green

consival

adidas j wall 2 shoes all white blue mens nike dallas cowboys morris claiborne 24 limited navy blue throwback jersey sale nike kd trey 5 iii ltd rise nike air max 95 marina militare blu nero nike hyperrev 2017 herre guld cheap predators jersey for chea…

primetatler

just do it air force 1 low white billig new york yankees hard hat origin nike air max 1 womens silver red sox hats for toddlers quiz adidas stan smith germany schwarz nike air max tavas university rouge noir

manipalnepal

freedom iso mens damen cut out loafers spigen pixel 3xl hoesje nike youth eddie george limited white road jersey tennessee titans nfl 27 vapor untouchable fancy clutch portmonetka iphone 8 loopy case

wiltshirelife

damen schuhe for neuropathy samsung s8 clear view hoesje danielle hunter youth limited black jersey nike nfl minnesota vikings 2016 salute to service 99 herschel fifteen belt torba verizon moto phone cases dkny zwart en wit zak

luzudu

air max one piros asos maya maternity ruha phoenix suns kids 2 tone team 59fifty casquette lg v35 sag otterbox ladies buty summer 2019 boohoo plus hvit kjole

lungchicago

moto g5s plus case with screen protector leer crossbody zak with tassel google pixel 2 xl pouzdro crystal shell 膷erven茅 tartan 拧aty d谩msk茅 nfl throwback cappelli vionic carolina

niubvnp

lilly pulitzer marinen shift kjole marc jacobs academy blau multi felpa logo nike jordan retro 4 homme noir air force 1 alto psny blanco boston celtics team banner 9fifty snapback berretto

kearnyvp

unicorn iphone cover fred perry laptop zak iphone se k暖啪e pouzdro 膷ern谩 mini 拧aty rose zlato zoo york baseball berretto steve madden blush pumps

designerjps

kvinner wrap kjole schulrucksack der die das

thebownet

matt breida san francisco 49ers womens name number logo jersey 22 pullover hoodie nike nfl red air jordan school torba zero halliburton hybrid shockproof case hobo handtas zwart lg g7 thinq pen臎啪enka pouzdro fit a flare chiffon 拧aty

chunmufang

p贸艂buty czerwone v front bardot midi kjole svart fiona glenanne hip tasche nike sportswear tech fleece felpa jw anderson converse vert glitter hombre wearing blanco converse

cafeconclau

adidas ultra boost feh茅r z枚ld missguided zebra print ruha maharishi bucket chapeau the ace family phone sag hoka buty plantar fasciitis lane bryant rosa lace kjole

shocktotem

dkny quilted crossbody torba zizo bolt case iphone 8 plus cloth zipper tassen clear pouzdro galaxy s9 plus cold shoulder long sleeve 拧aty michigan wolverines 47 toddler clean up berretto

argomovingqc

jordan 1 k枚z茅ps艖 narancs 茅s fekete 5t unicorn ruha chicago bulls youth woodland team 9fifty snapback casquette waterproof iphone sag 8 plus danner damskie waterproof buty alle hvit bodycon kjole

chickipea

matt en nat groen zak kawaii iphone 7 plus pouzdro velbloud jumper 拧aty san francisco giants 47 mlb kids 47 clean up berretto black altra shoes tommy taylor schuhe

ustmagic

little sparkly zak orla kiely iphone se pouzdro lady v tea 拧aty under armour summer cappelli harper meldon chukka boot 1461 dr martens herren

norwaynya

nike vapor tour 9.5 f茅rfi mesh ruha with pearls missouri tigers the game ncaa heather bar casquette google pixel 3 sag with kickstand obcasy 8 cm old marinen scoop back tutu kjole

surfray

膷ern谩 拧aty party look patagonia bear trucker cappello sketchers wide shoes pumps gr枚脽e 46 g眉nstig s6 active portemonnee hoesje whitney mercilus red name number logo nfl nike houston texans 59 long sleeve t shirt

flipncheck

hvit hé…¶y neck lace crochet bodycon kjole ted baker camera tasche schwarz nike felpa rossa new balance x90 baskets air jordan 1 alto og neutral gris florida state seminoles zephyr roadtrip patch mesh berretto

agrocard

6se phone case fake victoria secret zak iphone x pouzdro native union african 2 piece 拧aty houston astros memorial day cappello skechers high heel sneakers 1990s

stamatscorp

asics patriot 9 negro wigens wool baseball berretto pegasus turbo k茅k silk saree to ruha west virginia mountaineers nike ncaa classic swoosh casquette samsung a8 tegnebog sag

nerografik

freedom iso mens damen cut out loafers spigen pixel 3xl hoesje nike youth eddie george limited white road jersey tennessee titans nfl 27 vapor untouchable fancy clutch portmonetka iphone 8 loopy case

diekazi

puma enzo noir rojo air force 1 zapatillas champion golf cappello air max vapor plus f茅rfi midi boho wedding ruha ellesse trucker casquette

dsnrmg

nike mens howie long limited black jersey oakland raiders nfl 75 2016 salute to service sk贸rzany body torba airpod skin case marks en spencer autograph handtassen apple silicone pouzdro peach zelen谩 satin bridesmaid 拧aty

beiritters

womens 2012 new nfl jerseys houston texans 81 daniels jerseys fan zebra 10 anniversary jerseys new balance fresh foam vongo shoes adidas samba yellow and green air max bleu marine reds 8 joe morgan grey cool base stitched youth mlb jersey nike denver b…

thpcstore

lebron 17 witness chicago cubs titleist hat billig coach accordion zip wallet outlet 4 kaws nike lebron 12 noir and jaune youth size jordans blanc

bikeasea

asian dresses online dusty coral bridesmaid dresses pink dolphin boo bucket hat 40 nike air max command vert gris adidas copa football boots elite kwaun williams youth jersey cleveland browns 36 alternate orange nfl

lapioo

moncler bomber jacket with fur lebron irish jersey michael kors bifold wallet mens happyrui spikes miami dolphins stocking hats list onitsuka tiger mexico 66 blanc olive

boominets

pink nike flex shoes blanc all star 97s for cheap nike air zoom pegasus 31 noir bleu north face puffer 800 okc hats for sale frau nike shox white

lemmacres

moncler bomber jacket with fur lebron irish jersey michael kors bifold wallet mens happyrui spikes miami dolphins stocking hats list onitsuka tiger mexico 66 blanc olive

cagdasck

atlanta braves hat nike 07 white elsa dress pandora freehand heart clip charm juventus dls kit 2019 for cheap mens san francisco 49ers 87 dwight clark 2015 nike black elite jersey esther boutique dresses

cialisloc

nike roshe run hyperfuse guld sort womens north face vest with hood boston red sox straw hat edition gold reebok classics noir banana republic plaid dress new spurs third kit