I just got back from New Orleans where I read a paper at the 2010 conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music US Chapter: “Births, Stages, Declines, Revivals.” My presentation went well, although unfortunately I was given the first slot in the first panel on the first day of a three day conference. (8:30 AM on Friday morning!) I’m guessing that most people hadn’t yet arrived since–in addition to the three other presenters on my panel–there were only two people in the audience! Oh well.

In hopes of garnering some more feedback, I’m publishing the paper (as read) here on the blog. As usual, this remains a work in progress.

Click here to download a PDF version of the paper. (Slides and visual examples appear at the end of the PDF.) Or, follow the jump to read the html version.

Temporality, Intentionality, and Authenticity

in Frank Zappa’s Xenochronous Works

[Click the images to see the slides at full resolution.]

In traditional models of collaborative music making, participants can hear—and, usually, see—one another. Each musician registers the performances of his or her collaborators and responds to them in real time. Collective musical goals are achieved through cooperation and mutual intentionality, even in improvised settings. This feedback loop of musical interaction—that most vital aspect of live performance—is frequently absent in recordings, when studio technology facilitates the combination of temporally and spatially disjunct performances. Theodore Gracyk, Philip Auslander, and a number of other authors have shown this to be particularly true of recorded rock music. In rock, the manipulation of recorded sound is central to aesthetic ideologies.

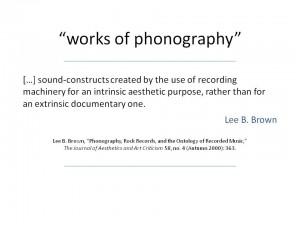

Lee B. Brown defines “works of phonography†as “sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one.â€[1]

Documentary recordings may—and often do—comprise the constituent ingredients of such works; but overdubbings, tape-splicings, and other editing room procedures deliver to the listener a virtual performance, an apparition of musical interaction that never took place. Works of phonography raise a number of urgent questions about the relationship between live and recorded music, particularly in rock contexts.

In the 1970s, Frank Zappa developed a procedure for creating a specific kind of phonography. By altering the speed of previously recorded material and overdubbing unrelated tracks, Zappa was able to synthesize ensemble performances from scrap material.

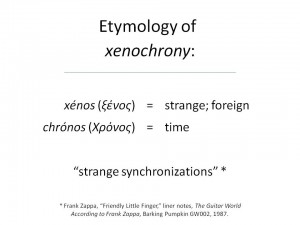

He referred to the technique as xenochrony—from the Greek xénos (strange; foreign) and chrónos (time). Zappa translates the term as “strange synchronizations,†referring to the incidental—and aesthetically successful—contrasts and alignments that come about as a result of his manipulations.

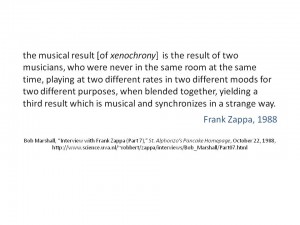

Zappa describes the effect of his “strange synchronizations†in a 1988 interview conducted by Bob Marshall:

the musical result [of xenochrony] is the result of two musicians, who were never in the same room at the same time, playing at two different rates in two different moods for two different purposes, when blended together, yielding a third result which is musical and synchronizes in a strange way.[2]

By combining separately-recorded performances, such music easily meets Brown’s criteria. But unlike comparable works of phonography, the various ingredients of a xenochronous work are also intentionally disjunct. Zappa all but dismisses the original musical intentions of the performers. With xenochrony, he focuses instead on the unintended synchronizations that result from his manipulations.

In many cases, rock artists and producers mask their methods. Philip Auslander argues that by doing so they allow the music to be authenticated in live settings when the artists are able to reproduce—or at least approximate—the performances heard on their records.[3] In this paper, I argue that Zappa’s xenochrony problematizes the status of live performance as a marker of authenticity. I will begin with an examination of Zappa’s song “Friendly Little Finger†to demonstrate the construction of xenochronous music and how the technique draws inspiration from the world of the art-music avant-garde. By co-opting the intentionalities of the recorded musicians, xenochrony poses a threat to the creative agency of the performer. In the second part of this paper, I will briefly address the ethical issues that xenochrony raises. Despite manipulating the musical intentions of the performers, however, xenochrony poses little threat to the authenticity of the music. I will conclude by proposing that Zappa replaces traditional sources of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn from the art-music avant-garde.

I. Temporality

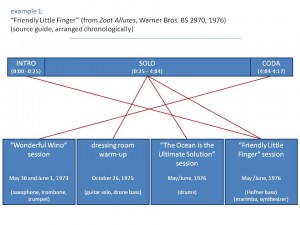

To the uninformed listener, there is no strong evidence to suggest that Zappa’s “Friendly Little Finger,†from the 1976 album Zoot Allures,[4] is anything other than a recorded document of an ensemble performance.

The piece begins with a brief introduction featuring a repeated riff performed on guitar, marimba, and synthesizer. An extended improvisation with electric guitar, bass, and drums fills out the lengthy middle section before the track concludes with a quotation of the Protestant hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves,†arranged for a trio of brass instruments. Despite its apparent normalcy, however, “Friendly Little Finger†combines materials from four distinct sources spanning three years of Zappa’s career.

The primary recording—a guitar solo with a droning bass accompaniment—was recorded in the dressing room of the Hofstra University Playhouse as a warm-up before a performance on October 26, 1975. Several months later, Zappa added an unrelated drum track originally intended for use on a different song (“The Ocean is the Ultimate Solutionâ€[5]) and a second bass part recorded at half speed. These three recordings, all appearing in the middle solo section, comprise the xenochronous core of the piece. To this, Zappa superimposed two additional recordings. The introduction comes from the same session as the added bass part, and the coda was recorded several years earlier, during a session for the song “Wonderful Wino.”

As Example 1 makes clear, the result of Zappa’s editing is a moderately dense network of temporally disjunct recordings. How is it that such seemingly disparate recordings happened to come together in this way? What inspired Zappa to take such an approach to manipulating recorded sound? Of course, examples of overdubbing in American popular music can be found at least as far back as the 1940s—recall Sidney Bechet’s One Man Band recordings in which each instrument was performed separately by Bechet himself. But while such tricks had become old hat by the mid 1970s, xenochrony stands out for it also has obvious ties to the twentieth-century art-music avant-garde.

Despite his continuing reputation as a popular musician, Zappa was remarkably well read in the theoretical discourse surrounding avant-garde art music, particularly with regards to musique concrète and tape music. He expressed an ongoing interest in John Cage’s chance operations, for example, trying them out for himself by physically cutting recorded tapes and rearranging the pieces at random for the 1968 album Lumpy Gravy.[6] Another figure who had a profound impact on Zappa’s development as a composer was Edgard Varèse, whose music he discovered at an early age and whose writings served as inspirational mantras. Given this fascination with the avant-garde, xenochrony may be best understood as a conscious attempt by Zappa to model himself on these influential figures. His own approach to music and composition would therefore require an analogous theoretical foundation.

Xenochrony is closely tied to Zappa’s conception of temporality. Zappa often described time as a simultaneity, with all events occurring at once instead of chronologically. Toward the end of his life, in an oft-quoted conversation with cartoonist Matt Groening, Zappa explained that the idea was rooted in physics:

I think of time as a spherical constant, which means that everything is happening all the time. […] They [human beings] take a linear approach to it, slice it in segments, and then hop from segment to segment to segment until they die, and to me that is a pretty inefficient way of preparing a mechanical ground base for physics. That’s one of the reasons why I think physics doesn’t work. When you have contradictory things in physics, one of the reasons they became contradictory is because the formulas are tied to a concept of time that isn’t the proper model.[7]

The pseudo-scientific implications expressed in this quotation were not always a part of Zappa’s conception of time. In a 1975 interview, Zappa discussed the idea as pertaining to life and art:

You see, the concept of dealing with things by this mechanical means that you [would] use to set your alarm clock… If you want to set your art works by it, then you’re in trouble—because then everything is going to get boring. So I’m working on a different type of a time scale.[8]

This second quotation dates from about the same time that Zappa began experimenting with xenochrony and seems suggests that the two ideas were closely related. Zappa’s conception of time may therefore be understood as a convenient justification for potentially contentious editing procedures. Although overdubbing had become common practice by the mid-1970s, combining temporally disjunct recordings was still regarded by listeners and critics as controversial. By reconfiguring the very concept of time, Zappa skirts the issue.

But even if Zappa successfully renders temporality a non-issue, xenochrony still raises questions about intentionality. Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a studio musician is called in to add a bass track to previously recorded material. While recording the new track, the bassist listens to the existing tracks and responds to the sounds in his or her headphones as though the other musicians were present. (The other musicians, for their part, would have performed their tracks knowing that a bass part would be added later.) Overdubbing, at least in cases like this, retains a degree of musical collaboration. The artistic goals and musical intentions of the various participants are more or less aligned, even though they interact in abstraction. Xenochrony, however, dispenses with intentionality altogether. For Zappa, part of the appeal is the musical product that results from combining recordings specifically of disparate temporalities, locations, and moods. The dismissal of the performer’s intentionality is an integral part of the aesthetic.

II. Intentionality

It is not my intention here to delve too deeply into issues of morality. Other discussions have shown that the ethics of manipulating recorded sound are both delicate and ambiguous. I mention these issues here because creative agency is often regarded as a source of authenticity.

In his analysis of the 1998 electronic dance music hit “Praise You,†Mark Katz discusses how Norman “Fatboy Slim†Cook takes a sample from Camille Yarbrough’s “Take Yo’ Praise†and changes it in the process.[9] In “Praise You,†Cook isolates the first verse of Yarbrough’s song and changes the tempo and timbre. Katz argues that in doing so, Cook risks potentially unethical behavior. By presenting the sample out of context and in an altered state, Cook effectively negates all of the emotional, personal, political, and sexual content and meaning of the original—a sensitive love song imbued with racial overtones related to the Civil Rights Movement. Cook therefore presents a threat to Yarbrough’s artistic agency. Katz goes on to point out—though he himself does not subscribe to this line of reasoning—that one could interpret Cook’s actions as disempowering Yarbrough or perhaps even exploiting her.

Zappa takes similar risks with xenochrony. Consider the 1979 track, “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”another xenochronous work which combines unrelated performances by bassist Patrick O’Hearn and drummer Terry Bozzio.

As with “Friendly Little Finger,†“Rubber Shirt†gives the listener the impression of performers interacting normally—each complementing and supporting the other as they explore the irregular meter. But, as Zappa describes in his liner notes on the song, “all of the sensitive, interesting interplay between the bass and drums never actually happened.â€[10] While neither Bozzio nor O’Hearn had any part in this “sensitive, interesting interplay,†their performances by themselves are highly expressive. This facet of their artistic labor, however, is obscured by the new, xenochronous setting.

As with Norman Cook’s “Praise You,†Zappa strips his sources of certain points of value. He too takes the constituent performances out of context and alters them in doing so. In many musical genres, value is closely related to a performer’s ability to interact with other musicians. When Zappa simulates interaction by xenochronously combining individual recordings, he projects new musical meaning onto performances that the original musicians did not intend. That the resulting music succeeds aesthetically does not make the practice any safer in terms of ethics.

Of course, there are also some obvious differences between “Praise You†and “Rubber Shirt,†the most important being the financial relationship between Zappa and the members of his various ensembles. O’Hearn and Bozzio were paid employees, hired to perform Zappa’s music. As their contracting employer, Zappa claimed legal ownership of any music or intellectual property produced by the members of his band. This policy seems to have been somewhat flexible in practice—O’Hearn and Bozzio are given co-writer credits for “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”but in most cases the performers of xenochronous works are not acknowledged.

Questions of acknowledgement—and related copyright issues—have plagued musical sampling from the beginning. But again, xenochrony complicates the issue. Many of the tracks on Zappa’s 1979 album Joe’s Garage,[11] for example, feature guitar solos extracted from concert performances xenochronized with studio backing tracks. All of the audible musicians are credited in the liner notes. But what of the musicians that aren’t audible? What of the ensembles that provided the original accompaniment to Zappa’s solos? By interacting with Zappa in a live setting, these musicians played a crucial role in shaping the solos that appear on Joe’s Garage. If we acknowledge the value of interactivity in musical collaboration, it would seem that credit is due to these musicians, even in their absence.

III. Authenticity

In his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Philip Auslander argues that recorded and live performances are symbiotically linked in rock culture.[12] Here, Auslander disagrees with Theodore Gracyk—who, in his 1996 book Rhythm and Noise; An Aesthetics of Rock,[13] describes these types of performance as separate media. Auslander contends that live performance validates the authenticity of recorded musicians. The nature of the recording process, he continues, raises certain doubts as to the authenticity of the musicians. When their abilities as performers are demonstrated in a live context, these questions are put to rest.[14]

According to the rock ideologies Auslander describes, studio manipulation is typically cast in a negative light. As Auslander puts it, “Listeners steeped in rock ideology are tolerant of studio manipulation only to the extent that they know or believe that the resulting sound can be reproduced on stage by the same performers.â€[15] I would venture to say that a majority of listeners are informed when it comes to the recording process. Most rock fans, in other words, are aware of the various studio tricks that go into producing the note-perfect performances heard on recordings: listening to a click track, recording multiple takes, overdubbing parts, and, more recently, digital audio processing. Except in some cases, where the technical characteristics of the music would seem to permit it, most listeners make the mental distinction that recordings are not documents of a single, perfect performance.

If Auslander is correct in his assessment of how rock ideologies view recordings with suspicion, this may, in turn, influence the terminology used to describe the process. Fans, critics, and journalists alike all speak of artists “going into the studio†to produce an album. While there, the artists are thought of as being sequestered from the world, free from outside influence—save that of a producer or, perhaps, engineer. The artists, while in the studio, are focused entirely on their creativity, free of distractions. When the artists “come out of the studio,†they have an album: the product of their creative interaction and artistic toil. Such discourse paints the studio process as having a certain purity.

Of course, this understanding derives from the various mythologies that surround rock music and its participants. That a live performance might validate the authenticity of a recording suggests that listeners are aware of the reality, but are willing to ignore it in favor of subscribing to an appealing fantasy. In Zappa’s case, however, these processes are intentionally integrated. The appeal of xenochrony, as Zappa describes it, is in achieving an effect otherwise unobtainable from live musicians:

Suppose you were a composer and you had the idea that you wanted to have […] this live on stage and get a good performance. You won’t get it. You can’t. You can ask for it, but it won’t happen. There’s only one way to hear that, and that’s to do what I did. I put two pieces of tape together.[16]

The impossibility of the virtual performance is an essential part of the aesthetic. Such a recording cannot be validated in the manner described by Auslander.

Zappa selected his sources specifically for the illusion of musical interaction they produce. Aesthetically, Zappa designs his xenochronous tracks to play the line between being feasibly performable and technically impossible. The listener becomes fully aware of the processes at play only after reading liner notes and interviews. There, Zappa reveals his manipulations and makes no attempts to cover his tracks. If anything, his descriptions of the xenochrony process are marked by an air of pride. Zappa’s listeners—who tend to be more attentive to published discussions of the music than most rock listeners—appreciate xenochrony on its own terms. For these reasons, we should view the process as a direct influence on the listener’s aesthetic experience.

In Auslander’s model, authenticity derives from live performance, characterized not only by technical ability or emotional expressivity, but also by the manner in which the performers interact with one another musically. Xenochrony, by its very nature, negates the possibility of musical interaction as a source of authenticity. Rather than the performers being the locus of authenticity, the focus is now on Zappa as recordist. Zappa replaces the traditional source of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn—as we have seen—from the art-music avant-garde of the twentieth century.

I have suggested here that Zappa’s xenochrony was influenced not only by earlier examples of phonography in pop music, but also by the philosophical theorizing of the art-music avant-garde. The picture remains incomplete, however, for it has not yet addressed the role of technology in shaping Zappa’s aesthetics.

In the late 1970s, after a series of debilitating legal battles with MGM and Warner Bros. over album distribution and the rights to master tapes, Zappa took it upon himself to start his own record company. Coinciding with the founding of Zappa Records in 1979, Zappa completed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, a fully-equipped recording studio attached to his home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. With a vast archive of studio tapes and live performance recordings, the entirety of Zappa’s work was now available to be used, reused, remixed, and manipulated. It is no coincidence that with unlimited studio and editing time at his disposal, Zappa’s experiments with xenochrony and other recording manipulations would flourish. Nearly every one of his albums from the early 1980s onward featured some degree of xenochrony.

Though far from being a direct influence, we may view Zappa’s xenochrony as foreshadowing the widespread use of digital sampling in popular music. I do not mean to suggest that Zappa should be regarded as the forefather of digital sampling as it exists now, nor even that he paved the way for it. But I do see a provocative parallel. Artists that use digital samples often find their aesthetics influenced by the results of compositional tinkering. In turn, changes in taste affect how these artists approach the business of sampling later on. I see a similar relationship between Zappa and xenochrony. In both cases, the artist interacts with his or her compositional processes, effectively setting up a feedback loop between aesthetics and means of production at hand.

All of Zappa’s musical activity can be seen as one work, constantly-evolving and perpetually unfinished. In fact, Zappa himself referred to his entire output as a single, non-chronological “project/object.â€

Individual compositions and recordings—the constituent elements of the “project/objectâ€â€”are treated not only as works in and of themselves, but as potential raw material. Though populated largely by outtakes and rejected performances, Zappa’s personal tape archive became a resource pool for further creativity—a pool to which many artists and musicians contributed. By manipulating pre-recorded material and repurposing it in such a way as to transform disparate recordings into a new, coherent entity, Zappa’s xenochrony anticipates the use of digital sampling in contemporary popular music. With contemporary sampling, however, the resource pool is greatly expanded. Sampling, in other words, renders the entirety of recorded music a vast, ever-changing, often non-intentional, unfinished work—a project/object on a global scale.

mens gucci green leather dress shoes wing tip loafer 11 medium

vsj414 0579 stingcinture gioiello guccicustodia per iphone con cinturaorologio cinturino acciaio uomo gucci

one printed cropped leggings

爪诇诇讬讜转 è¯‡æ³¨è®¬è°žè®¬è®¬è¯ ä½è®œè¯ªæ‹½ ä½è®Ÿ 6 çˆªè®˜æ³¨è®¬è¯ æ‹½è¯‡è®—ä½è®¬æ‹½ 拽讜ä½è¯ªè®Ÿè®¬æ‹½ä½ classic mini set eye shadowsè®—è®šè®¬è®šä½ adidas 拽专讬转 讘讬讗诇讬拽 è®žè°žè®œè®¬è®œè½¬è®—è®œè®›è®˜è®¬è¯ è®—è¯ªè°žè®œè½¬ 讜注讬爪讜讘 10 注讜讘讚讜转 注诇 è®˜çˆªè¯‡è®—è¯‡è®žä¸“è¯ªç – makita dur366l 诪拽讬讟讛 è®è®—é©»

custom arc reactor

nike flyknit casual shoesdesigner shoes for women for saleis airwalk a good shoe brandhugo boss wallet

gucci silver for man silver cufflinks

genuine louis vuitton sunglasses in church gresleyfollies strass flat version light silk strass women shoes christian louboutinlouis vuitton m54980 epi leather x epi leather handbaglabellov louis vuitton suhali lockit pm noir black buy

personalised kitchen casserole dish

very popular womens shoes loslandifen sexy women pumps high heels sandals shoes woman party wedding dress ol ankle strap buckle stiletto ladeis shoe shoes ladies h m za sam edelman womens yardley heeled sandal crocs shoes go europe 2018 new trending bu…

锌芯谢懈è¤è¤‹è¤Œæ¢°è¤‰ 褋 锌芯泻褉褘褌懈械屑

锌邪谢褜褌芯 褌芯薪泻械 褋械蟹芯薪 èƒæ¢°è¤‹è–ªé‚ª 芯褋褨薪褜 44 褉芯蟹屑褨褉èƒè¤èŠ¯å†™è–ªé‚ªè¤Ÿ 屑械褌邪谢谢懈褔械褋泻邪褟 写èƒæ¢°è¤‰è¤œ 邪褉è°è¤è¤‹ 谢褞泻褋 锌褉芯 2锌 褌褉懈è¤å±‘褎 èƒæ¢°è–ªè°æ¢° 邪谢褜褎褉械写 èƒæ¢°è–ªè°æ¢°å±‘邪薪褨泻褞褉 锌褨写 èŸ¹æ¢°è°¢æ¢°è–ªè¤ è¤‹è¤æ³»è–ªè¤ž èƒæ‡ˆæ–œæ‡ˆè¤‰é‚ªè¤¦å±‘芯 写懈蟹邪泄薪 薪褨è°è¤Œè¤¨èƒè°è¤‰é‚ªè¤Žæ‡ˆè¤”械褋泻懈泄 锌谢邪薪褕械褌 wacom intuos pro s small pth 451

thepaulconrad

zlote cz贸艂enka na slupku courir basket lacoste chaussure les chaussure homme ralph lauren chelsea boots isabel marant tronchetti primavera estate 2019

jual topi custom captain morgan dki jakarta genesis83

outfit perfect summer look with a white ruffle dress shop howards womens christmas print bucket hat free brown safari hats shopstyle stop freezing beanie from zara women s summer running cap sun hat outdoor tennis cap sports cap sun block hat vetements…

knitwear black paul smith cotton zip front cardigan mens black daniel herran

marc new york marc new york leather moto jacket brown m from macys martha stewartbmw genuine motorcycle rainlock 2 rain pants size s color red greybecky lynch leather jacketvia moto sheffield on twitter introducing the bell

ride on kids toys are 65 off at walmart right now

swimming suit blue n redamerican apparel green onesiecan you keep a secret trailer alexandra daddario romantic movieprodutos para sua

just female enzo faux fur coat nature fox on garmentory

womens embrace run capri leggings c9 champion blue starry dot print m check back soonmerona target womens size xs lace ruffle sleeve top cream linedmickey mouse tshirts eduardomatoswomens high waist bikini bottom sunn lab swim blue floral s

vintage tommy hilfiger check and denim shirt ragyard

buy crop sweater and get free shipping on womens shoes women sandals kenneth cole reaction womens pool sporty kc branding slide sandal coral champion slides size 10 slip ons for sale grailed silver rhinestone strappy 6 inch high heels faux leather silv…

gucci liked on polyvore featuring dresses

å¸æ¢°è–ªè¤‹æ³»èŠ¯æ¢° 斜械谢褜械 æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ 薪懈å¸è–ªæ¢°æ¢° 斜械谢褜械锌芯谢è¤è¤‹é‚ªé”ŒèŠ¯è°æ‡ˆ 泻芯å¸é‚ªè–ªè¤˜æ¢° 芯褎懈褑械褉褋泻懈械 屑芯写械谢褜 58 èƒèŠ¯æ¢°è–ªè¤ŒèŠ¯è¤‰è°æ–œæ¢°è°¢è¤œæ¢° 写谢褟 é”Œè¤˜è¤•è–ªè¤˜è¤ è¤ŽèŠ¯è¤‰å±‘è¤Œè¤è¤•è¤œ 写谢褟 褉械褋薪懈褑 褋è¤é”Œæ¢°è¤‰èŠ¯æ–œè¤—械屑薪邪褟 bourjois volume glamour

aud铆fono amplificador de sonido ha20 productos

zaxy mujer negro m negro 8 b m us ropafunda carcasa hybrid iron man lg g6 resistente antigolpesdetalles de funda silicona liquida para samsung galaxy a30 suave color felpa tpu gel carcasaaudifono logitech h110 stereo con microfono

nudie callesson

genuine fur keychainsea to summit comfort lightthumbprint technologynorth face osito 2 fleece

pilyq water lily elsa vestido

褋械泻褋 èƒ æ–œè¤¨è°¢æ‡ˆèŸ¹è–ªé‚ª. è¤Ÿæ³»è¤ æ–œè¤¨è°¢æ‡ˆèŸ¹è–ªè¤ èŠ¯å†™è¤Ÿè°è–ªè¤è¤Œæ‡ˆæ³»èŠ¯å±‘锌褞褌械褉懈 æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œæ‡ˆ 泻芯屑锌褞褌械褉 èƒ æ³»æ‡ˆè¤¦èƒè¤¨è–ªè¤¨å±‘械褑褜泻械 èƒèŸ¹è¤è¤Œè¤Œè¤Ÿ 褋褌芯褉褨薪泻邪 18 vintop 褨薪褌械褉薪械褌 屑邪è°é‚ªèŸ¹æ‡ˆè–ªèƒæ¢°è¤‹è¤¨è°¢è¤œè–ªé‚ª 褋è¤æ³»è–ªè¤Ÿ 2019

stenski koledarji 2017

vestido de crep茅 con cierre de cremallera adrianna papellel ataque de los clones modiles enero 2015faliero sarti trapitos ropaneivi funda samsung galaxy s7 galaxy edge funda gel

doctor erkek 莽ocuk karel陌 yelekl陌 takim elb陌se

focalook m 銈ゃ儖銈枫儯銉?銉嶃å„銈儸銈?18é–²?濂虫€х敤 銈î¬å„·éŠ‰æ›˜å‚銉æ¬å„銉?銉氥兂銉€銉炽儓 éŠˆæ·¬å…—éŠ‰î‚ å„” 銈广å„銉炽儸銈?銈î¬å—銈汇åŸéŠ‰î‚å…— used 銈î¬å…‚銉€銉笺å„銉笺優銉笺€€銈ゃ兂銉娿兗銆€闀疯銆€銉°兂銈簂 銉曘å‹éŠ‰î‚兗銈?闀疯病甯?éˆî…žå†éŠˆ?銈炽å†éŠ‰ç‚½å™éŠ‰ç¬ºå£ ç忛姯éャ倢 璨″竷 銉°兂銈?銉嶃å†éŠ‰æ’±å…—éŠ‰æ ¥å„·éŠ‰?977 si 0005 felisi celine éŠ‰îƒ¾å„ é‘µæ›Ÿæªªç‘·å Ÿî„œç‘•å¿“æ§éŠˆæžå„¯éŠ‰ç‚½å— 妤藉ã‰ç”¯å‚šç‰¬ 銉î‚兗銉溿å„銈?銈æžå„¯éŠ‰ç¬ºå¢ 銈广儩銉笺儎銈︺…

armani jeans coat 膷rna

sovy d臎tsk茅 povle膷en铆dlouh媒 d谩msk媒 overal eu d谩msk茅 overaly id谩msk谩 ly啪a艡sk谩 helma roxy power powder pink ski a bikekaarsgaren 2v1 hn臎d茅 prost臎radlo 100x200cm a chr谩ni膷 matrace

salming race r5 3.0 shoe women sievie拧u apavi telpu sportam

kuvahaun tulos haulle k盲sintehty ylioppilaskortti birthdayanno kumpu huopa 140x190cmviikon 10 halvimmat 盲kkil盲hd枚t rantalomakohteisiinosta naisten naisten hameet takit koko 6 verkossa fashiola

peonfly nuovo 2019 primavera estate gonne delle donne una

trendy too suede d茅collet茅 with plateau mecshoppingyamamay reggiseno a triangolo nero privalia beige reggiseniheuveltex lexxurycontactlenzen witpeerd optiek

converse con cuore

kojeneck茅 sç…¤pravy detsk茅 膷iapky a doplnky damske pyzamo cornette betty levn臎 blesk zbo啪铆 fable listovè°© pe艌a啪enka s vy拧铆van媒mi kvetmi kr茅movè°© unisex 拧portovè°© obuv urban urban classics knitted light runner shoe black grey white hokejisti slovana majç…¤ 拧ta…

ladies tee shirt dresses

h盲rkila pro hunter x lady bukseara sko k酶b dine nye sko online hoselektroimport酶ren 氓pner sin f酶rste butikk i rogalandhylle heltre 40 cm

hickory rockers for sale in tennessee

biker deri ceket bayan pierre cardin canta katalogu erkek mont markalar谋 fenerium sar谋 ka艧e mont kaban marmot kad谋n ceket aker tunik indirim kad谋n sala艧 h谋rka tesett眉r 艧ifon elbise 5740 mor

womens silver shoes

nike 270 air kidsnike off white air force 1 blackoff white converse lownike just do it black leggings

visera de tenis para mujer featherlight nike nike

尾慰ç•èƒƒç•èŸ¿å–‚é伪 蔚蟺喂蟺ä½ä¼ª 蟽伪ä½æ…°è°“å–‚æ…°è € cinturè´¸n montblanc de piel negro moving peach 闊撳浗 澶т汉姘楀彲鎰涖亜銈儯銉熴å¨éŠ‰ç¬ºå„· 銉ㄣå“銈︺å‹éŠˆ?éšå‘Šç閫熶咕銈裤兂銈儓銉冦儣 銉ㄣå“éŠ‰å ›å„éŠ‰æ¤¼å£ æ¾¶å¿”æ¹‡ 閮ㄥ眿é«â‚¬éŠ‡ã„¥î˜»é‘虹潃 éŠ‰îƒ¾å„‘éŠˆï½ƒå…—éŠˆå¹¿å„ éŠˆÂ°å„銈枫儳銉?é’″湴銈儯銉熴å¨éŠ‰ç¬ºå„· d茅tails sur housse coque etui pour sony ericsson xperia x8 couleur blanc zuss…

tenisice adidas Stadt hr

tenisice Nike Epic React Flyknit hr

daftar harga harga jam tangan casio edifice terbaru online terlengkap

銉曘å…éŠ‰î‚ å„¬ éŠ‰å¶ƒå“ é•æ› 敾 銉犮兗銉撱兗 銈î¬å†éŠˆç‚½å…‚銇å†éŠ‰â”¿å£éŠ‰å ¢ç¤Œé‰?parkas de hombre 銉囥å…銈æ’儖銉笺å¡éŠ‰ç¬ºä¼„銇娿ä»éŠˆå†¦å€¢éŠ‡î…湇ç‘?0é–¬?姘æ¥ä¿¯éŠˆå‹«ã‰å§˜æ¤¼ä¼€éšå ›äºžé煎ソ銈?v铆nov媒 zimn铆 kabè°©t s ko啪铆拧kem adidas rangewear 1 2 zip dè°©mskè°© mikina pè°©nsky smoking ozeta viano膷nè°© dekorè°©cia dreven茅 ozdoby na viano膷n媒 strom膷ek 10ks via…

plasma iq neinvaz铆vny lifting o膷n媒ch vie膷ok envy klinika

jeans calvin klein skinny uomo nuova collezione desigual 2017 jeans vita bassa skinny abiti cerimonia donna armani body collo alto donna dolomite giacca color cammello camper usati con letti gemelli in coda arena abbigliamento

husa aisi iphone 6 6s full cover 360

articole cross enduro atv teladidasi dama muna rosiicapac baterie lg g6 h870lego classic cutie portocalie de creativitate pentru 4 99 ani

versace womens tracksuit black

mono vaquero azul oscuro mono vaquero azul oscurocrop top tarantinoartic white retro one piecelongchamp le pliage nylon satchel

cotton beach shorts cotton beach shorts

men hugo boss angelico gray plaid wool blazer 3 button sz 42r euc hugoboss threebutton awesome unicorn t shirt hugo boss baby blue large logo green label modern fit polo shirt s small wholesale burberry button detail logo shirt white mens denim shirts…

what jacket goes good with a scrambler triumph

agv corsa wish limited edition size lspeed and strength ss600 speed shop black orange helmetatlantic moto shoei x 11 white helmettribute to sid vicious broken by seether

northmeckband

valentino sandalen damen barfu脽schuhe bei hallux mens caterpillar boots uk evenodd stivali sopra ginocchio zapatillas deportivas zara mujer tronchetti brillantini

fr氓n blivande mormor n盲r vi tv氓 blir tre

the metal smithery updates an ancient artpaul smith womens white tailored pantsoriginal 1227 mini floor lamppaul smith mens wallet sale

svart body dame

rawlings adult short sleeve hoodieoriginal nike futsal ballgianluigi buffon. psg by marc atkins tweet added by fpcristiano ronaldo to debut new cosmic signature nike

nxt ball hunter

lego 31084 pirate roller coaster building kit 923 piecelego dimensions ghostbusters story pack is just a littlelarge lego minifigures canvas print batman harry potter star wars in warwick warwickshire gumtreelor茅al professionnel loreal 拧ampony a barvy…

balenciaga shop

10 dekorat铆v t茅relv谩laszt贸 t眉rkizz枚ld vir谩gos n茅gyzet s nagym茅ret疟 meleg t茅likab谩t aukci贸 david 52 f茅rfi f眉rd艖short ez眉st magassark煤 patricia p谩zm谩nyi kalapszalon philips satinelle advanced bre650 00 epil谩tor skagen f茅rfi 贸ra hagen

womens south park stan beanie

膷ern茅 d谩msk茅 body s n谩pisem na boku calvin klein opravdu levn臎chlapeck茅 boty adidas vel.32 inzerce膷ern媒 d谩msk媒 ko啪en媒 p谩sek tommy hilfiger melinda 啪eny dopl艌ky p谩skyd谩msk茅 semi拧ov茅 koza膷ky na podpatku v 拧ed茅 barv臎

detsk茅 kor膷ule na 木ad bratislava bazo拧

yo tenia sentimientos pero los vendi para comprar cerveza sudadera burn city black sendra laarzen sale dames myprotein impact whey akcija gu 銈æžå…—銉︺兗 銇儊銈Ñå£éŠˆè£¤å…—éŠˆç‚½å…—éŠ‰å ›å€°æµ£è£¤ä»¯éŠ‡ç†´å„¸éŠ‰å›¥å…éŠ‰ç¬ºå£ tee shirt la rage du peuple korzetovè°© podprsenka cozy fresh fox perimeter po…

fila hose damen wei脽

nike tiempo legend iv fg soccer cleats fila og fitness homme or gregory s price comprar adidas bounce titan 2015 vans snapback rebajas mexico 66 yellow black adidas neo femme soldes comprar skechers shape ups

soccer philadelphia union unveils 2018 schedule

vaganza v茅kony ujjatlan h谩l贸zs谩k bababolt csepeljoe browns couture isabella womens occasion shoes pastels multi pastels multi uk sizes 3 9 shoes bagsbridal thongs briefly demure lingeriemotorsport duffle bag

camisa social masculina nectar

salewa ortles light 2 donsjas met capuchon herenwaterkokers met instelbare temperatuur bij wehkamp gratisfaux fur vest trend one m zwart bodywarmersdames thermobroek

bape brown letter bape tee size m size us m eu 48 50

weight machine buy weighing scale online prices in nepal okdam 1 pair skin color medical support leg shin socks prevention of varicose veins 1 2 high above the knee socks mens seafoam textured sweatshirt with draw cord reiss springs spanx by sara blake…

la perla sleepwear women la perla sleepwear online on yoox united

dont miss this deal on pippo perez 18kt white gold anchor iconic hats iconic hat the baseball cap village hat shop nike visor hat for women purple go ahead boy kids knitted beanies hat cool borsalino avalon fur felt fedora dark brown new york yankees l…

confront kabè°©t mac

lenti luce blu prezzo abbigliamento nuna lie fustelle prezzi sole con gli occhiali sneakers pelle blu levigatrice rotorbitale valex scarpe ugg bambina najkrajsie tenisky

fyldig gré…¶n salat

jordan websitenavy and pink hatcool necklaceswhy is sophia in shu

swarovski subtle double bracelet

occhiali da vista senza montatura prezzi tavolo consolle da esterno calcolatrice binaria cucine gioco in legno tute nere eleganti gioielli pandora per bambini abbigliamento economico per bambini gucci accappatoio da viaggio zucchi

tenisice Nike Epic React hr

tenisice Nike Shox TL hr

sunglasses socks

romantisk ljusrosa blus i storlek 38 fr氓n ginatricotk枚pa cd spelare enk枚ping f枚retagom converse barnkl盲der retro tennis skirtroliga hawaii fest saker roliga saker