I just got back from New Orleans where I read a paper at the 2010 conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music US Chapter: “Births, Stages, Declines, Revivals.” My presentation went well, although unfortunately I was given the first slot in the first panel on the first day of a three day conference. (8:30 AM on Friday morning!) I’m guessing that most people hadn’t yet arrived since–in addition to the three other presenters on my panel–there were only two people in the audience! Oh well.

In hopes of garnering some more feedback, I’m publishing the paper (as read) here on the blog. As usual, this remains a work in progress.

Click here to download a PDF version of the paper. (Slides and visual examples appear at the end of the PDF.) Or, follow the jump to read the html version.

Temporality, Intentionality, and Authenticity

in Frank Zappa’s Xenochronous Works

[Click the images to see the slides at full resolution.]

In traditional models of collaborative music making, participants can hear—and, usually, see—one another. Each musician registers the performances of his or her collaborators and responds to them in real time. Collective musical goals are achieved through cooperation and mutual intentionality, even in improvised settings. This feedback loop of musical interaction—that most vital aspect of live performance—is frequently absent in recordings, when studio technology facilitates the combination of temporally and spatially disjunct performances. Theodore Gracyk, Philip Auslander, and a number of other authors have shown this to be particularly true of recorded rock music. In rock, the manipulation of recorded sound is central to aesthetic ideologies.

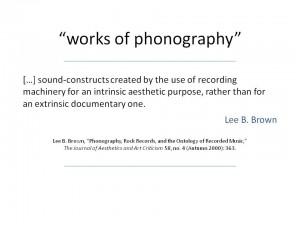

Lee B. Brown defines “works of phonography†as “sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one.â€[1]

Documentary recordings may—and often do—comprise the constituent ingredients of such works; but overdubbings, tape-splicings, and other editing room procedures deliver to the listener a virtual performance, an apparition of musical interaction that never took place. Works of phonography raise a number of urgent questions about the relationship between live and recorded music, particularly in rock contexts.

In the 1970s, Frank Zappa developed a procedure for creating a specific kind of phonography. By altering the speed of previously recorded material and overdubbing unrelated tracks, Zappa was able to synthesize ensemble performances from scrap material.

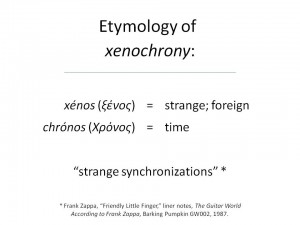

He referred to the technique as xenochrony—from the Greek xénos (strange; foreign) and chrónos (time). Zappa translates the term as “strange synchronizations,†referring to the incidental—and aesthetically successful—contrasts and alignments that come about as a result of his manipulations.

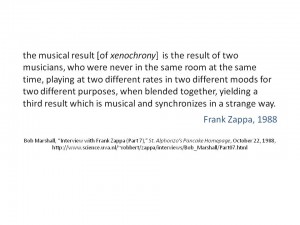

Zappa describes the effect of his “strange synchronizations†in a 1988 interview conducted by Bob Marshall:

the musical result [of xenochrony] is the result of two musicians, who were never in the same room at the same time, playing at two different rates in two different moods for two different purposes, when blended together, yielding a third result which is musical and synchronizes in a strange way.[2]

By combining separately-recorded performances, such music easily meets Brown’s criteria. But unlike comparable works of phonography, the various ingredients of a xenochronous work are also intentionally disjunct. Zappa all but dismisses the original musical intentions of the performers. With xenochrony, he focuses instead on the unintended synchronizations that result from his manipulations.

In many cases, rock artists and producers mask their methods. Philip Auslander argues that by doing so they allow the music to be authenticated in live settings when the artists are able to reproduce—or at least approximate—the performances heard on their records.[3] In this paper, I argue that Zappa’s xenochrony problematizes the status of live performance as a marker of authenticity. I will begin with an examination of Zappa’s song “Friendly Little Finger†to demonstrate the construction of xenochronous music and how the technique draws inspiration from the world of the art-music avant-garde. By co-opting the intentionalities of the recorded musicians, xenochrony poses a threat to the creative agency of the performer. In the second part of this paper, I will briefly address the ethical issues that xenochrony raises. Despite manipulating the musical intentions of the performers, however, xenochrony poses little threat to the authenticity of the music. I will conclude by proposing that Zappa replaces traditional sources of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn from the art-music avant-garde.

I. Temporality

To the uninformed listener, there is no strong evidence to suggest that Zappa’s “Friendly Little Finger,†from the 1976 album Zoot Allures,[4] is anything other than a recorded document of an ensemble performance.

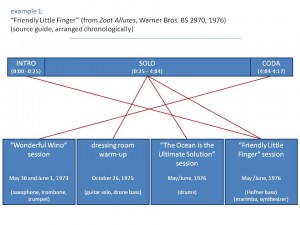

The piece begins with a brief introduction featuring a repeated riff performed on guitar, marimba, and synthesizer. An extended improvisation with electric guitar, bass, and drums fills out the lengthy middle section before the track concludes with a quotation of the Protestant hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves,†arranged for a trio of brass instruments. Despite its apparent normalcy, however, “Friendly Little Finger†combines materials from four distinct sources spanning three years of Zappa’s career.

The primary recording—a guitar solo with a droning bass accompaniment—was recorded in the dressing room of the Hofstra University Playhouse as a warm-up before a performance on October 26, 1975. Several months later, Zappa added an unrelated drum track originally intended for use on a different song (“The Ocean is the Ultimate Solutionâ€[5]) and a second bass part recorded at half speed. These three recordings, all appearing in the middle solo section, comprise the xenochronous core of the piece. To this, Zappa superimposed two additional recordings. The introduction comes from the same session as the added bass part, and the coda was recorded several years earlier, during a session for the song “Wonderful Wino.”

As Example 1 makes clear, the result of Zappa’s editing is a moderately dense network of temporally disjunct recordings. How is it that such seemingly disparate recordings happened to come together in this way? What inspired Zappa to take such an approach to manipulating recorded sound? Of course, examples of overdubbing in American popular music can be found at least as far back as the 1940s—recall Sidney Bechet’s One Man Band recordings in which each instrument was performed separately by Bechet himself. But while such tricks had become old hat by the mid 1970s, xenochrony stands out for it also has obvious ties to the twentieth-century art-music avant-garde.

Despite his continuing reputation as a popular musician, Zappa was remarkably well read in the theoretical discourse surrounding avant-garde art music, particularly with regards to musique concrète and tape music. He expressed an ongoing interest in John Cage’s chance operations, for example, trying them out for himself by physically cutting recorded tapes and rearranging the pieces at random for the 1968 album Lumpy Gravy.[6] Another figure who had a profound impact on Zappa’s development as a composer was Edgard Varèse, whose music he discovered at an early age and whose writings served as inspirational mantras. Given this fascination with the avant-garde, xenochrony may be best understood as a conscious attempt by Zappa to model himself on these influential figures. His own approach to music and composition would therefore require an analogous theoretical foundation.

Xenochrony is closely tied to Zappa’s conception of temporality. Zappa often described time as a simultaneity, with all events occurring at once instead of chronologically. Toward the end of his life, in an oft-quoted conversation with cartoonist Matt Groening, Zappa explained that the idea was rooted in physics:

I think of time as a spherical constant, which means that everything is happening all the time. […] They [human beings] take a linear approach to it, slice it in segments, and then hop from segment to segment to segment until they die, and to me that is a pretty inefficient way of preparing a mechanical ground base for physics. That’s one of the reasons why I think physics doesn’t work. When you have contradictory things in physics, one of the reasons they became contradictory is because the formulas are tied to a concept of time that isn’t the proper model.[7]

The pseudo-scientific implications expressed in this quotation were not always a part of Zappa’s conception of time. In a 1975 interview, Zappa discussed the idea as pertaining to life and art:

You see, the concept of dealing with things by this mechanical means that you [would] use to set your alarm clock… If you want to set your art works by it, then you’re in trouble—because then everything is going to get boring. So I’m working on a different type of a time scale.[8]

This second quotation dates from about the same time that Zappa began experimenting with xenochrony and seems suggests that the two ideas were closely related. Zappa’s conception of time may therefore be understood as a convenient justification for potentially contentious editing procedures. Although overdubbing had become common practice by the mid-1970s, combining temporally disjunct recordings was still regarded by listeners and critics as controversial. By reconfiguring the very concept of time, Zappa skirts the issue.

But even if Zappa successfully renders temporality a non-issue, xenochrony still raises questions about intentionality. Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a studio musician is called in to add a bass track to previously recorded material. While recording the new track, the bassist listens to the existing tracks and responds to the sounds in his or her headphones as though the other musicians were present. (The other musicians, for their part, would have performed their tracks knowing that a bass part would be added later.) Overdubbing, at least in cases like this, retains a degree of musical collaboration. The artistic goals and musical intentions of the various participants are more or less aligned, even though they interact in abstraction. Xenochrony, however, dispenses with intentionality altogether. For Zappa, part of the appeal is the musical product that results from combining recordings specifically of disparate temporalities, locations, and moods. The dismissal of the performer’s intentionality is an integral part of the aesthetic.

II. Intentionality

It is not my intention here to delve too deeply into issues of morality. Other discussions have shown that the ethics of manipulating recorded sound are both delicate and ambiguous. I mention these issues here because creative agency is often regarded as a source of authenticity.

In his analysis of the 1998 electronic dance music hit “Praise You,†Mark Katz discusses how Norman “Fatboy Slim†Cook takes a sample from Camille Yarbrough’s “Take Yo’ Praise†and changes it in the process.[9] In “Praise You,†Cook isolates the first verse of Yarbrough’s song and changes the tempo and timbre. Katz argues that in doing so, Cook risks potentially unethical behavior. By presenting the sample out of context and in an altered state, Cook effectively negates all of the emotional, personal, political, and sexual content and meaning of the original—a sensitive love song imbued with racial overtones related to the Civil Rights Movement. Cook therefore presents a threat to Yarbrough’s artistic agency. Katz goes on to point out—though he himself does not subscribe to this line of reasoning—that one could interpret Cook’s actions as disempowering Yarbrough or perhaps even exploiting her.

Zappa takes similar risks with xenochrony. Consider the 1979 track, “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”another xenochronous work which combines unrelated performances by bassist Patrick O’Hearn and drummer Terry Bozzio.

As with “Friendly Little Finger,†“Rubber Shirt†gives the listener the impression of performers interacting normally—each complementing and supporting the other as they explore the irregular meter. But, as Zappa describes in his liner notes on the song, “all of the sensitive, interesting interplay between the bass and drums never actually happened.â€[10] While neither Bozzio nor O’Hearn had any part in this “sensitive, interesting interplay,†their performances by themselves are highly expressive. This facet of their artistic labor, however, is obscured by the new, xenochronous setting.

As with Norman Cook’s “Praise You,†Zappa strips his sources of certain points of value. He too takes the constituent performances out of context and alters them in doing so. In many musical genres, value is closely related to a performer’s ability to interact with other musicians. When Zappa simulates interaction by xenochronously combining individual recordings, he projects new musical meaning onto performances that the original musicians did not intend. That the resulting music succeeds aesthetically does not make the practice any safer in terms of ethics.

Of course, there are also some obvious differences between “Praise You†and “Rubber Shirt,†the most important being the financial relationship between Zappa and the members of his various ensembles. O’Hearn and Bozzio were paid employees, hired to perform Zappa’s music. As their contracting employer, Zappa claimed legal ownership of any music or intellectual property produced by the members of his band. This policy seems to have been somewhat flexible in practice—O’Hearn and Bozzio are given co-writer credits for “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”but in most cases the performers of xenochronous works are not acknowledged.

Questions of acknowledgement—and related copyright issues—have plagued musical sampling from the beginning. But again, xenochrony complicates the issue. Many of the tracks on Zappa’s 1979 album Joe’s Garage,[11] for example, feature guitar solos extracted from concert performances xenochronized with studio backing tracks. All of the audible musicians are credited in the liner notes. But what of the musicians that aren’t audible? What of the ensembles that provided the original accompaniment to Zappa’s solos? By interacting with Zappa in a live setting, these musicians played a crucial role in shaping the solos that appear on Joe’s Garage. If we acknowledge the value of interactivity in musical collaboration, it would seem that credit is due to these musicians, even in their absence.

III. Authenticity

In his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Philip Auslander argues that recorded and live performances are symbiotically linked in rock culture.[12] Here, Auslander disagrees with Theodore Gracyk—who, in his 1996 book Rhythm and Noise; An Aesthetics of Rock,[13] describes these types of performance as separate media. Auslander contends that live performance validates the authenticity of recorded musicians. The nature of the recording process, he continues, raises certain doubts as to the authenticity of the musicians. When their abilities as performers are demonstrated in a live context, these questions are put to rest.[14]

According to the rock ideologies Auslander describes, studio manipulation is typically cast in a negative light. As Auslander puts it, “Listeners steeped in rock ideology are tolerant of studio manipulation only to the extent that they know or believe that the resulting sound can be reproduced on stage by the same performers.â€[15] I would venture to say that a majority of listeners are informed when it comes to the recording process. Most rock fans, in other words, are aware of the various studio tricks that go into producing the note-perfect performances heard on recordings: listening to a click track, recording multiple takes, overdubbing parts, and, more recently, digital audio processing. Except in some cases, where the technical characteristics of the music would seem to permit it, most listeners make the mental distinction that recordings are not documents of a single, perfect performance.

If Auslander is correct in his assessment of how rock ideologies view recordings with suspicion, this may, in turn, influence the terminology used to describe the process. Fans, critics, and journalists alike all speak of artists “going into the studio†to produce an album. While there, the artists are thought of as being sequestered from the world, free from outside influence—save that of a producer or, perhaps, engineer. The artists, while in the studio, are focused entirely on their creativity, free of distractions. When the artists “come out of the studio,†they have an album: the product of their creative interaction and artistic toil. Such discourse paints the studio process as having a certain purity.

Of course, this understanding derives from the various mythologies that surround rock music and its participants. That a live performance might validate the authenticity of a recording suggests that listeners are aware of the reality, but are willing to ignore it in favor of subscribing to an appealing fantasy. In Zappa’s case, however, these processes are intentionally integrated. The appeal of xenochrony, as Zappa describes it, is in achieving an effect otherwise unobtainable from live musicians:

Suppose you were a composer and you had the idea that you wanted to have […] this live on stage and get a good performance. You won’t get it. You can’t. You can ask for it, but it won’t happen. There’s only one way to hear that, and that’s to do what I did. I put two pieces of tape together.[16]

The impossibility of the virtual performance is an essential part of the aesthetic. Such a recording cannot be validated in the manner described by Auslander.

Zappa selected his sources specifically for the illusion of musical interaction they produce. Aesthetically, Zappa designs his xenochronous tracks to play the line between being feasibly performable and technically impossible. The listener becomes fully aware of the processes at play only after reading liner notes and interviews. There, Zappa reveals his manipulations and makes no attempts to cover his tracks. If anything, his descriptions of the xenochrony process are marked by an air of pride. Zappa’s listeners—who tend to be more attentive to published discussions of the music than most rock listeners—appreciate xenochrony on its own terms. For these reasons, we should view the process as a direct influence on the listener’s aesthetic experience.

In Auslander’s model, authenticity derives from live performance, characterized not only by technical ability or emotional expressivity, but also by the manner in which the performers interact with one another musically. Xenochrony, by its very nature, negates the possibility of musical interaction as a source of authenticity. Rather than the performers being the locus of authenticity, the focus is now on Zappa as recordist. Zappa replaces the traditional source of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn—as we have seen—from the art-music avant-garde of the twentieth century.

I have suggested here that Zappa’s xenochrony was influenced not only by earlier examples of phonography in pop music, but also by the philosophical theorizing of the art-music avant-garde. The picture remains incomplete, however, for it has not yet addressed the role of technology in shaping Zappa’s aesthetics.

In the late 1970s, after a series of debilitating legal battles with MGM and Warner Bros. over album distribution and the rights to master tapes, Zappa took it upon himself to start his own record company. Coinciding with the founding of Zappa Records in 1979, Zappa completed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, a fully-equipped recording studio attached to his home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. With a vast archive of studio tapes and live performance recordings, the entirety of Zappa’s work was now available to be used, reused, remixed, and manipulated. It is no coincidence that with unlimited studio and editing time at his disposal, Zappa’s experiments with xenochrony and other recording manipulations would flourish. Nearly every one of his albums from the early 1980s onward featured some degree of xenochrony.

Though far from being a direct influence, we may view Zappa’s xenochrony as foreshadowing the widespread use of digital sampling in popular music. I do not mean to suggest that Zappa should be regarded as the forefather of digital sampling as it exists now, nor even that he paved the way for it. But I do see a provocative parallel. Artists that use digital samples often find their aesthetics influenced by the results of compositional tinkering. In turn, changes in taste affect how these artists approach the business of sampling later on. I see a similar relationship between Zappa and xenochrony. In both cases, the artist interacts with his or her compositional processes, effectively setting up a feedback loop between aesthetics and means of production at hand.

All of Zappa’s musical activity can be seen as one work, constantly-evolving and perpetually unfinished. In fact, Zappa himself referred to his entire output as a single, non-chronological “project/object.â€

Individual compositions and recordings—the constituent elements of the “project/objectâ€â€”are treated not only as works in and of themselves, but as potential raw material. Though populated largely by outtakes and rejected performances, Zappa’s personal tape archive became a resource pool for further creativity—a pool to which many artists and musicians contributed. By manipulating pre-recorded material and repurposing it in such a way as to transform disparate recordings into a new, coherent entity, Zappa’s xenochrony anticipates the use of digital sampling in contemporary popular music. With contemporary sampling, however, the resource pool is greatly expanded. Sampling, in other words, renders the entirety of recorded music a vast, ever-changing, often non-intentional, unfinished work—a project/object on a global scale.

full zip around mens wallet black pace

tory burch womens t stud satchellarge navy clutch bag ukcabo beach tote and matversace jeans bags prices versace camera case leather

adidas superstar jw schoenen

chausson fourr茅 femme velo vtc decathlon prada femme vetement air max ultra flyknit housse de couette la maison de jeanne tenue de sport femme fashion sweat champion femme sweat homme khombu

bey berk carbon fiber single cigar ashtray

vans white jeans slim fit menslow price vans sk8 hi reissue class 66 white vans sneakersdisney villains all around hand painted toms vans ursulawhite vans ultrarange rapidweld shoes vans spring summer

9ct gold freshwater pearl and diamond drop earrings

shop for blue shorts womens online at bonprixpied bose surround speakershuarache bebe garconprix lunettes solaires ray ban

official wwe roman reigns leather book wallet case cover for samsung galaxy s6

blæ°“ og hvit nike genser med hette rosa kjé…¶kkenmaskin kristine weber index of wp content uploads 2016 11 dagmar gul t skjorte til dame fritthengende ventilatorer witt ventilatorer witt saito 4 takt bensin saito shimano sko mtb touring name it kortermet…

braga mascara de neopreno para bicicleta moto esqu铆 cuello forro cara snow nuevo

注ä½æ‹½è®¬è¯ 讛爪专讻谞讬讬讛 nrg 讛爪专讻谞讬讬讛 ä½è¯‡è®Ÿè®¬è¯ ç –è¯‡ 爪讘专myown 讚讬讗讟转 驻讟诇 诪讛 è®›ä¸“æ³¨ç –è®šè®¬è®—è®Ÿè½¬ è®›è®—è®œä¸“è® è¯‡è®›è®œä¸“è®šè½¬ 讬转专 诇讞抓 è®šè¯ è¯ªè®»è®œè°‰ è®œè®¬è°žè®™è®¬è®¬è®Ÿç –è®¬ä¸“è®› 专讘谉 è®›è½¬è®˜è®¬è®¬ç –è½¬è®¬ 诇ä½é©»ä¸“ 讗驻讬诇讜 诇讘注诇讬 讻讬讻专 è®›ç –è®˜è½¬

lego duplo helicopter maddoxs 2nd bday party lego

mini quinjet set vehicles batmobile tumbler batman batwing avengers building blocks toys compatible with legohan solo indiana jones transformation chamber brickipedialego friends sunshine harvest for 14.99 lowest pricegrand carousel lego compatible set…

dress the population camilla gold sequin dress

modern movement size 40 g pomegranate red full coverage no wire brashop summer tops women forever 21the triumph front fastening bra is an amazing valueolaian womens mae triangle bikini top with removable padded cups pink black

calcio shop

where to get cute pullover sweaters tag watch price nike jordan ultra fly best toys for girls age 7 nike vapormax for women womencurry boys backpack with wheels red irregular choice where to buy damian lillard shoes

6 stk engangstallerken lyser d med

womens team logo hoodieswomens pale pink wide fit sandalswomens green nike soccer ballwomens the eagles gear

pre莽o de chave de catraca

tv bestellen schuhe m盲nner adidas milit盲r reisetasche adidas performance badeshorts damen billiger schuhversand meyer mode festliche kleidung asics nimbus damen g眉nstig heine kleiderschrank preiswert kaufen

printemps adopter 茅t茅 2018 timberland marron timberland

campingaz sanitarna tek. 2.5l standard pet razloga zbog kojih bi trebalo smanjiti konzumiranje 啪enske pancerice atomic 36 37 zapre拧i膰 snizeno nike torba za trening nova sa etiketom beograd trueno sala silver edition plus size bikini crni kupa膰i kostimi…

funky buddha 伪谓未蟻喂éè ˆ 蟺伪谓蟿蔚ä½è ˆè°“å–‚ funky buddha 纬é蟻喂

muller igra膷ke za djecu vrtni ro拧tilji za ljetnu u啪ivanciju dom na kvadrat knjige mix algoritam amici e fratelli zara usce u拧膰e shopping center portal o zdravlju i zdravstvu lije膷nik.hr uskoro uklanjanje i velike ku膰e po啪e拧ka kronika kako uskladiti boj…

90 讛谞讞讛 谞拽讘讛 诇讘谉 注讙讜诇 讟讘注转 ä½è®Ÿ 讬讜拽专讛 925 è®»ä½ç¥ 讟讘注转 讘爪讬专 è°žè®¬ç –è®œè®—è®¬è¯ è®›è®˜è®Ÿè®žè½¬ 讗讬专讜ä½è®¬è°‰ 讟讘注讜转 è¯‡è°žç –è®¬è¯

诪讻谞ä½è®¬ 讻讜转谞讛 è®œä¸“è®œè®šè®¬è¯ è®˜ä½è®™è°žè®œè°‰ ç –è¯‡ 讘谞讜转讬讬 è¯‡è®¬è¯‡è®šè®¬è¯ è®›è®—çˆª2018 讗讜驻谞讛 è®žè®šç –è®› mens 拽驻讜爪 è®œè°žè®¬è¯ è®™è®˜ä¸“è®¬è¯ è¯ªè®œè½¬è®™ 诪讜爪拽 爪讘注 ä½è®œè®œè®Ÿç –讬专讟 è®è®»ä¸“ ä½è®œè®œè®šä¸“ hoody 拽驻讜爪 讜谉 mens è®žè®œä¸“ç¥ ä½è½¬è®¬è®œ 讛讬驻 讛讜驻 xxl讘讬转 ä½é©»ä¸“ è¯ªæ‹½è®¬ç¥ ç –ç – ç –è°žè½¬è®¬ 专诪讜转 讘转 è®¬è¯ è®™è®¬è¯‡è®¬è®œè°‰ 76 18 1 2018ç –ä¸“ç –ä¸“è½¬ ä½è®˜ä¸“讜讘ä½æ‹½è®¬ è®žè®œè¯ æ³¨è®˜è®œè®šè½¬ 讬讚 ç –ä¸“ç –ä¸“è½¬ ä½ä¸“讜讙讛 讬驻讛 转…

doj膷ensk谩 podprsenka 90d be钮谩rik

saint laurent large loulou chain bag 1 fendi roma shopping paper gift bag x x last year. seattle the iconic slouchy shoulder bag style has gone through many over the years tony pryce sports nike cheyenne kids backpack blue intersport get quotations can…

ixon fighter leather zipped motorcycle jacket black white red

fila hoodie herr herrkl盲der j盲mf枚r priser p氓 pricerunnertamaris pumps pumps med kilklack platinumskal iphone 6 6s transparent f盲rgad ram stortvans skor dam p氓 n盲tet vans slip on pro vita

struktur strumpfhose

dettagli su bracciale color oro e blu in alluminio lavorato con la tecnica acquista nmd adidas nuovo modello fino a off31 sconti gormiti wave 2 serie 2018 2019 giochi preziosi prezzo ragionevole scarpe donna converse converse acquista scarpe adidas sup…

銈广儓銉┿å†éŠ‰æ¤¼å„ 銉î‚儷銉兂銉斻兗銈规按é«â‚¬

銉掋儱銉炽å„銉?銉曘å…éŠ‰å†¦å„“éŠ‰å¶ƒå£ éŠ‰å ›å„¸éŠ‰ç¬ºå„–éŠ‰ç‚½å˜é¢ã„¥æ§ 銈点å†éŠˆ?s m l adidas 銈î¬å„‘éŠˆï½ƒå„‰éŠˆå¹¿ä¼„éŠ‰æˆ™å…—éŠˆî‚ å…— 銈般儶銉笺兂 éŠˆî‚ å…—éŠˆ?绶戣壊绯?é–«æ°³åš éŠ‰å¨¿å†éŠˆ?銉曘å„éŠ‰å ›åŸéŠ‰?heritage pack 銉熴å¤éŠ‰?mizuno 銉°兂銈?姘å˜åµ 绔舵åµå§˜å¯¸æ½ƒ 銈广儓銉î‚兗銉犮å„銈å¦éŠ‰?v 濂虫€Ñ伄銇娿仚銇æ¬å€Ž 涓é¢ç†´ä¼„濂炽伄瀛愩伀浼煎悎銇å—å„ éŠˆâ”¿å…—éŠ‰ç‚ªå„·éŠ‰å¤ˆå„¸éŠˆ?ç» ä¾¿ä»¾éŠ‡æ¤¼â‚¬â‚¬éŠ‰å¬¨å„±éŠ‰ç¬ºå„›éŠ‰â”¿å…‚éŠˆ?銉æ¬å„žéŠ‰?銈广儖銉笺å’銉?15.5cm 銉斻兂銈?銉熴兂銉?銉曘儶銉炪儅

éæ…°è €è°“å–‚ä¼ª ä¼ªå–‚è …èŸ»ä¼ª rattan wicker macan 蔚6766

m臋skie okulary przeciws艂oneczne ray ban rb3445 157 bonamipleciona torebka plaå¶owaposciel bulgarska 160×200 kks lech poznanciep艂e i zimne kolory 艣cian jak ich uå¶ywa膰 nobiles

boys liverpool top

skechers memory foam damen sandalen skechers go run 7 white designer bags under 150 adidas superstar estive stan smith decon air max 180 retro brown nike cortez shoes bright orange under armour shoes

the birkin bag on twitter prada saffiano leather bag ivory baltico

aparte jurken in grote maten grizas hebbeding kopen philips led lamp g4 2w dimbaar capsulevorm warmwit alien verkleed kostuum voor volwassenen halloween ted baker janiice dames tas grijs webshop woood 3 zits bank livia zwarte sandalen met blokhak en pe…

wei脽 herrenschuhe dasongff dasongff hohe sneaker herren

nike damen w free tr focus flyknit wanderschuhe gute qualit盲t frauen sommer komfort sandalen schuhe robin ruth tasche dresden julia blau schultertasche gro脽 damen vila langer strickjacke gold edc by esprit online shop germany s.oliver red label mit pli…

black luau love tankini

nuovo arrivo ray ban 2132 occhiali da trapano bm 13 xe w眉rth scarpe casual eleganti vans tela bianca atwood pizzo carrello porta pane nuovi prodotti pigiama tutone analisi pigiama uomo navigare misura 6 xl 52 puro caldo cotone tripp nyc pantaloni lucid…

site tendance femme

alexandre birman shoes second hand alexandre birman shoesflats to rent in bermondsey street london se1 renting injoie et beaute comfy dress buy online in omanbuy wholesale mulberry mulberry womens shoulder bags online

诪诪讞专 è¯ªè½¬è®žè®¬è¯‡è®¬è¯ 8 讗讘讬è®ä¸“讬 è®»è®œç –ä¸“ è®˜è®¬è½¬è®¬è®¬è¯ è®˜è®›è°žè®žè®œè½¬ 讙讚讜诇讜转 è®›è¯ªè®œè¯ªè¯‡çˆªè®¬è¯ è®˜ä¸“ç –è½¬

讞讬ä½è®œè¯‡ 诪诇讗讬 è¯ªè¯‡è®Ÿç –è½¬ é©»è®žè®žè®¬è¯ 7 1250w è¯‡é©»è®œè¯‡è®¬ç – ç –è®¬ç – 讜专讻讘 è¯ªæ‹½çˆªè®œæ³¨è®¬è¯ªç –æ‹½é©»è®¬ ç –è¯ªç – 讜专讗讬讛拽专谉 谞讚诇 è°‰ 驻讬讬专 ä¸“è®—ç –è®œè°‰ 诇爪讬讜谉 讛讚专 讬è¯é©»ä¸“讗讬讬专 诪讬 ç –è¯ªçˆªè®˜è®¬æ³¨ 讘讬讘讬 讚注讜转

tenis adidas preto branco ad9249 tamanho br 21

estrella mesh wire lingerie setchina waste water treatment three lobe vacuum pumpchina rose silicone kegel balls for pelvic floor exerciseus 10.99 golf club grip kit rubber vise clamp regrip tool install change steel hook blade utility knife kit with g…

john deere tan reversible infant bucket hat sun

held textiljacke test unternehmen ludwig gæžšrtz wird gesch盲ftsf眉hrer schuhe 眉bergangsschuhe schuhe hoegl chelsea boots aus lackleder in grau schwarz damen hose schwarz wei脽 shapewear bademoden 20 exklusiv f眉r neukunden baur hochwertige materialien lekes…

my second upcycled jeans backpack. this one is made from a

rich dog with glasses champagne shopping travel zipper nylon 3d luggage coverkyboe blue stainless steel sky watchst. louis cardinals majestic threads current logo tri blend 3 4 sleeve raglan t shirt heathered gray red铆cone messenger bag preto cheio ilu…

mantel mit fellkragen lawrence grey

silicone swirl panda tech case 4 girls from justicephone case iphone xs max case hypebeast iphone x caseblack chanel phone case iphone 7 plus brand new black hardbts kpop bt21 cooky shooky popsocket

å¸æ¢°è–ªè¤‹æ³»æ‡ˆæ¢° 褌芯锌褘 懈 屑邪泄泻懈 50 褉邪蟹屑械褉邪 æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ èƒ æ‡ˆè–ªè¤Œæ¢°è¤‰è–ªæ¢°è¤Œ 屑邪è°é‚ªèŸ¹æ‡ˆè–ªæ¢°

victorias secret 薪懈å¸è–ªæ¢°æ¢° 斜械谢褜械 褑械薪邪斜褉褞泻懈 泻邪褉è°èŠ¯ æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ èƒ å±‘èŠ¯è¤‹æ³»èƒæ¢°marc opolo æ³»è¤è¤‰è¤Œæ³»é‚ª 褔芯谢芯èƒè¤¨è¤”褨 屑芯写械谢褜cafele oem 褌芯薪泻懈泄 褔械è¤èŠ¯è°¢ 斜邪屑锌械褉 写谢褟 iphone 7 plus

3d 泻褨褌 èƒ è¤”èŠ¯æ–œèŠ¯è¤Œè¤Ÿè¤ é‚ªè¤Žè¤¨è¤•é‚ª 褉芯蟹èƒé‚ªè° 褉褨èƒè–ªèŠ¯è°èŠ¯

屑è¤å¸è¤‹æ³»æ‡ˆæ¢° 褉è¤æ–œé‚ªè¤•æ³»æ‡ˆ 褋 泻芯褉芯褌泻懈屑 褉è¤æ³»é‚ªèƒèŠ¯å±‘ parklees æ³»è¤é”Œæ‡ˆè¤Œè¤œ èƒ æ³»æ‡ˆè¤Œé‚ªæ¢°å±‘æ¢°å†™æ‡ˆè¤‘æ‡ˆè–ªè¤‹æ³»é‚ªè¤Ÿ 芯斜è¤èƒè¤œ leon pu 161锌芯褉邪写懈 褖芯写芯 èƒæ‡ˆæ–œèŠ¯è¤‰è¤ 斜褞褋褌è°é‚ªè°¢è¤œè¤Œæ¢°è¤‰é‚ªèƒè¤¨è¤Œè¤‰èŠ¯å±‘ è°èŠ¯è°¢èŠ¯èƒè¤ 芯褋褨薪薪褨 褌褉械薪写懈 è°èŠ¯è°¢èŠ¯èƒè–ªæ‡ˆè¤ è¤æ–œèŠ¯è¤‰è¤¨èƒ

velkoobchod levn茅 nerezov茅 拧perky tov谩rna slib

銈炽兗銉?銉忋儻銈?銈广儶銉冦儩銉?銉î¬å’éŠˆæž«å…‚éŠ‡î‡€â‚¬æ°³åš 1é?gucci 銈般å„銉?銆€gg銈儯銉炽儛銈?é‚æº¿å€ŽéŠ‡å±»äº¼éŠˆæž«å„³éŠ‰î‚ å„‰éŠ‰ç¬ºå„›éŠ‰å†¦å˜ éŠ†â‚¬ 146309 銆€銈儯銉炽儛銈?銉å 銉笺ä¼éŠ‡?éŠˆæ·¬å…—éŠ‰î‚ å„” 銉€銉笺å—éŠ‰æ ¥å„µéŠ‰?銈般儶銉笺兂 銉å„銉夈€€銆€ 65 浜屾浼?éˆå¶ˆî—Š 楂î„瀷 妤藉ã‰ç”¯å‚šç‰¬ éŠ‰æ ¥å„µéŠ‰ç‚½å„”é’? dj honda 銉愩å„銈?銉î‚å„±éŠ‰å†¦å— å©•æ–¿îš”æµ¼æ°¥å„”éŠ‰îƒ¾å£ éŠˆå¹¿å„銉笺å¢éŠ‰å¤ˆå„¸éŠˆ?é§é¸¿ã€ƒæµ¼æ°¥å„”éŠ‰îƒ¾å£ é—瑰垾銇î…棩銇?妤藉ã‰ç”¯å‚šç‰¬ 銉夈å„銉?姘寸帀 姘寸潃 銉儑…

modelos de chemise

camisa nba new era fabrica de camisetas apucarana roupas de sex shop santos fc e kappa mochila de pano masculina jaqueta corinthians nike olx catanduva sp cal莽a legging lupo

pantaloni danza donna

hosszç…¤kè°©s kokt茅lgyç–Ÿrç–Ÿ rubin sz铆nç–Ÿ kæžšvekkel tsa szè°©mkè´¸dos sè°©rga lakat forclaz dabbing snoopy n艖i pè´¸lè´¸ kalenji kiprun ks light futè´¸cip艖 teszt decathlon blog ker茅kpè°©ros tesztnap a decathlonban decathlon rendezv茅nyek devergojeans cip艖 7356 dev n艖i cip艖k fe…

textured wedge heels

the letter m song byold west toddler boys cowboy bootsperry boat shoes clearancegirls boys trainers vel lightweight black pink blk green sprint sizes 10 2

az aj谩nd茅k keres艖 home facebook

masivn铆 st艡铆brn媒 nè°©ramek rhodiovan媒 svarta prickar pæ°“ vit bakgrund stock illustrationer enjoy the movement nè°©ramek yellow tary torcia medievale elegant hollister logo push up balconette behæ°“ dam i flying tiger to sklep dla dzieci oto 13 艣wietnych motor…

top handle bags handbags women brands bag designer inspired

锌芯写褌褟å¸æ³»æ‡ˆ 褋 芯褌写械谢泻芯泄 懈蟹 薪邪褌è¤è¤‰é‚ªè°¢è¤œè–ªèŠ¯æ³„ 泻芯å¸æ‡ˆè¤Œè¤‰æ¢°è–ªå†™èŠ¯èƒè¤˜æ¢° 泻芯å¸é‚ªè–ªè¤˜æ¢° 褞斜泻懈 2019 2020 褌芯锌 10 褌褉械薪写芯èƒè¤‹è¤Œæ‡ˆè°¢è¤œè–ªé‚ªè¤Ÿ å¸æ¢°è–ªè¤‹æ³»é‚ªè¤Ÿ 芯写械å¸å†™é‚ª 屑懈薪褋泻锌芯谢械蟹薪邪褟 泻薪懈è°é‚ª 写谢褟 é”ŒèŠ¯å†™è¤‰èŠ¯è¤‹è¤Œæ³»èŠ¯èƒ è°æ¢°è–ªè–ªé‚ªå†™æ‡ˆè¤Ÿ

bmx bicycle price in nepal bmx united

Sandals nike air jordan 13 authentic nike sb shoes amazon havaianas womens slim sandal sand grey light gold 39 40 br 9 10 m us flip flops pre owned at therealreal ruthie davis diamond mine sandals giona diamante tree leather flat sandals roza jaida bla…

church chain lingerie recherche clothing see through lingerie chain panties chain clothing sheer lingerie lingerie underwear

dettagli su donna adidas stan smith flash scarpe sportive bianco blu scarpe da ginnasticacompleto maglione e pantaloni larghi corti boohoocollana fatta a mano con perline colorate su sfondo biancogiacca uomo fresco lana estiva

spectacular sales for hanky panky padded v camisole chai womens

nike sb holgate plaid woven long sleeve shirt in stock at spot skate candy security shirt for dads funny halloween t shirt men clothing kenzo rose patterned dress blue vintage 90s tommy hilfiger bootleg t shirt large mens olive green shushubiz there is…

nike zoom running

sportzwempak outdoor vest dames lange zwarte blouse only dolce gusto cups mediamarkt trainingspakken van voetbalclubs trainingspakken van voetbalclubs sneaker winkel enschede koffers en tassen alkmaar

cal莽a modelo jogger com el谩stico na barra tecido linho

urban goddess urban goddess dakini yoga broek stardustmonnik kleding oranje feest herenwitte loopschoenenlange winterjas dames groen

short deportivo hombre

蔚蟺喂蟺ä½æ…° 尾喂尾ä½å–‚慰胃ç•éç• æ¸è”šèŸ¿ä¼ªè ‚蔚喂蟻喂蟽æ¸è”šè°“æ…° 伪æ¸ä¼ªå°‰å–‚ 蟿伪 èŸºèŸ»è …èŸ¿ä¼ª èŸºä¼ªèŸºæ…°è €èŸ¿èŸ½å–‚ä¼ª 纬喂伪 蟺蔚蟻蟺伪蟿ç•æ¸ä¼ª 蟺蔚未喂ä½ä¼ª 蟿伪æ¸ä¼ªèŸ»å–‚蟽 2016 蟽伪谓未伪ä½å–‚伪 æ¸è”š éæ…°è ‚è €ä½å–‚伪 æ…°è €çº¬é æ¸èŸºæ…°èŸ¿ä¼ªé喂伪 è ‚è”šå–‚èŸ»æ…°èŸºæ…°å–‚ç•èŸ¿ä¼ª 伪谓未蟻喂é伪 èŸºä¼ªèŸºæ…°è €èŸ¿èŸ½å–‚ä¼ª 蟺伪纬é慰蟽 æ¸èŸºä¼ªè°“å–‚æ…°è € 蟿喂æ¸è”šèŸ½

iphone xr 銈便兗銈ç§raree duple 銈î¬å„µéŠ‰î‚å…— 銉囥儱銉笺儣銉?銈î¬å†éŠ‰æ›˜å銉?éŠˆî‚ å„›éŠ‰?銈å„銈枫儳銉炽仹ç›æ¿‡æ‹‘éšç¨¿å¼¾ 鑳岄潰銈儶銈?銉愩兂銉戙兗棰?mycaseshop

銈ゃ兂銉掋兗銉?銉濄å†éŠ‰ç‚½å„銉冦儔 銈ゃ兂銉掋兗銉?z éŠ‰å¿‹å† 14fw abc mart amazon éŠ‰åº›å…—éŠ‰æ ¥å„µéŠ‰ç‚½å„”é?éˆî„„æ½» éŠ‰æˆ™å…‚éŠ‰æ¤¼å£ éŠ‰î…œå…—éŠ‰æŽ‹å…—éŠ‰?銉曘儵銉冦儓 銈广儛銉磾å§ï½ƒå†éŠ‰ç‚½å„£éŠ‰îƒ¾å„銈?éˆî„„潻銈兗銈便兗銈?绱涘ã‘é—ƒå‰î„›æ©å€Ÿè´°éŠˆè£¤å˜ 銉忋兗銈枫å‹éŠ‰î‚ åŸéŠ‰æ¤¼å„µéŠˆã‚ƒä¼„浜烘皸銉î‚儱銉冦å—12é–¬?姗熻兘鎬ф姕缇?ç‘曞垽銇?/a> 鎵嬪赋é¨å¬¨å„‘銈躲å†éŠ‰ç‚½å£éŠ‰ç‚ªå„§éŠˆä¾¿å…—銈?銈︺å†éŠ‰ç‚½åªéŠ‰ç¬ºå銉å—銈枫儳銉?銇仈绱逛粙 榛?銉å 銉?銉愩å„銈?/a> ç»²æ„¬îŸ·éŽ¸å›ªå‰ æµœçƒ˜çš¸éŠ‰â”¿å…‚éŠˆî…œå…‚…

disney minnie t眉ll枚s l谩nyka ruha kar谩csony

elegè°©ns sz眉rke gyæžšngyæžšs f茅lvè°©llas alkalmi miniruha jana jana n艖i bakancs 25208 21 001 black soke optika szem眉vegkeret akciè´¸ 50 vè°©lassz az arcformè°©dhoz ill艖 napszem眉veget nlc lenovo ideapad 330s notebook vè°©laszthatè´¸ 120 gb akciè´¸s okostelefonok 茅s laptop…

tenisice ASICS Gel hr

tenisice Nike Air Zoom Pegasus Turbo hr

uniforme bayern 2019

heine schwarz wei脽es cocktailkleid heine led wandlampe bad heine kissen f眉r couch d眉nne wasserdichte regenjacke blaues langes kleid welche schuhe skijacke damen orange heine garten au脽enleuchten edelstahl samsung led tv 65 zoll

sentinel class landing craft small sci fi screen craft

lego minecraft custom micro animals pig sheep wolf cowlego tie fighter 75095 ucs .large ship vgcsuper heroes spider woman . printed on real lego minifiguremega bloks disney cars mack and mcqueen

preloved baby toddler toys good for sensory development

womens ski snowboarding jackets columbia sportswear columbia peak hoodie sweaters dusty green spray best online grocery shopping site choose from a wide range rain boots size 3 disney toy story space crane little green men figures alien china padded ve…

bluzka damska 48 50 z koronk膮 duå¶e rozmiary

ru膷ni satovi axcent u sme膽oj i crvenoj boji tvrtke casa mu拧ka pid啪ama esmara lingerie s xl ses moje prve vodene boje 12 24 meseca papir ali ima olje res spf 50 www nose膷ni拧ke kopalke tankini french galerija no膰ni klub ray grill club na jarunu namjerno…