I just got back from New Orleans where I read a paper at the 2010 conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music US Chapter: “Births, Stages, Declines, Revivals.” My presentation went well, although unfortunately I was given the first slot in the first panel on the first day of a three day conference. (8:30 AM on Friday morning!) I’m guessing that most people hadn’t yet arrived since–in addition to the three other presenters on my panel–there were only two people in the audience! Oh well.

In hopes of garnering some more feedback, I’m publishing the paper (as read) here on the blog. As usual, this remains a work in progress.

Click here to download a PDF version of the paper. (Slides and visual examples appear at the end of the PDF.) Or, follow the jump to read the html version.

Temporality, Intentionality, and Authenticity

in Frank Zappa’s Xenochronous Works

[Click the images to see the slides at full resolution.]

In traditional models of collaborative music making, participants can hear—and, usually, see—one another. Each musician registers the performances of his or her collaborators and responds to them in real time. Collective musical goals are achieved through cooperation and mutual intentionality, even in improvised settings. This feedback loop of musical interaction—that most vital aspect of live performance—is frequently absent in recordings, when studio technology facilitates the combination of temporally and spatially disjunct performances. Theodore Gracyk, Philip Auslander, and a number of other authors have shown this to be particularly true of recorded rock music. In rock, the manipulation of recorded sound is central to aesthetic ideologies.

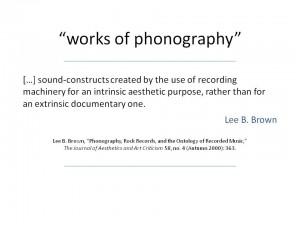

Lee B. Brown defines “works of phonography†as “sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one.â€[1]

Documentary recordings may—and often do—comprise the constituent ingredients of such works; but overdubbings, tape-splicings, and other editing room procedures deliver to the listener a virtual performance, an apparition of musical interaction that never took place. Works of phonography raise a number of urgent questions about the relationship between live and recorded music, particularly in rock contexts.

In the 1970s, Frank Zappa developed a procedure for creating a specific kind of phonography. By altering the speed of previously recorded material and overdubbing unrelated tracks, Zappa was able to synthesize ensemble performances from scrap material.

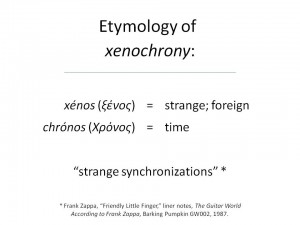

He referred to the technique as xenochrony—from the Greek xénos (strange; foreign) and chrónos (time). Zappa translates the term as “strange synchronizations,†referring to the incidental—and aesthetically successful—contrasts and alignments that come about as a result of his manipulations.

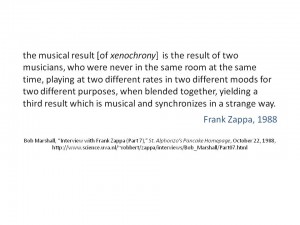

Zappa describes the effect of his “strange synchronizations†in a 1988 interview conducted by Bob Marshall:

the musical result [of xenochrony] is the result of two musicians, who were never in the same room at the same time, playing at two different rates in two different moods for two different purposes, when blended together, yielding a third result which is musical and synchronizes in a strange way.[2]

By combining separately-recorded performances, such music easily meets Brown’s criteria. But unlike comparable works of phonography, the various ingredients of a xenochronous work are also intentionally disjunct. Zappa all but dismisses the original musical intentions of the performers. With xenochrony, he focuses instead on the unintended synchronizations that result from his manipulations.

In many cases, rock artists and producers mask their methods. Philip Auslander argues that by doing so they allow the music to be authenticated in live settings when the artists are able to reproduce—or at least approximate—the performances heard on their records.[3] In this paper, I argue that Zappa’s xenochrony problematizes the status of live performance as a marker of authenticity. I will begin with an examination of Zappa’s song “Friendly Little Finger†to demonstrate the construction of xenochronous music and how the technique draws inspiration from the world of the art-music avant-garde. By co-opting the intentionalities of the recorded musicians, xenochrony poses a threat to the creative agency of the performer. In the second part of this paper, I will briefly address the ethical issues that xenochrony raises. Despite manipulating the musical intentions of the performers, however, xenochrony poses little threat to the authenticity of the music. I will conclude by proposing that Zappa replaces traditional sources of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn from the art-music avant-garde.

I. Temporality

To the uninformed listener, there is no strong evidence to suggest that Zappa’s “Friendly Little Finger,†from the 1976 album Zoot Allures,[4] is anything other than a recorded document of an ensemble performance.

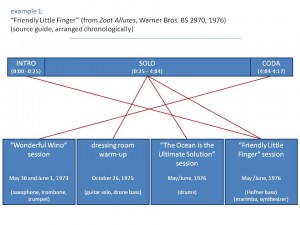

The piece begins with a brief introduction featuring a repeated riff performed on guitar, marimba, and synthesizer. An extended improvisation with electric guitar, bass, and drums fills out the lengthy middle section before the track concludes with a quotation of the Protestant hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves,†arranged for a trio of brass instruments. Despite its apparent normalcy, however, “Friendly Little Finger†combines materials from four distinct sources spanning three years of Zappa’s career.

The primary recording—a guitar solo with a droning bass accompaniment—was recorded in the dressing room of the Hofstra University Playhouse as a warm-up before a performance on October 26, 1975. Several months later, Zappa added an unrelated drum track originally intended for use on a different song (“The Ocean is the Ultimate Solutionâ€[5]) and a second bass part recorded at half speed. These three recordings, all appearing in the middle solo section, comprise the xenochronous core of the piece. To this, Zappa superimposed two additional recordings. The introduction comes from the same session as the added bass part, and the coda was recorded several years earlier, during a session for the song “Wonderful Wino.”

As Example 1 makes clear, the result of Zappa’s editing is a moderately dense network of temporally disjunct recordings. How is it that such seemingly disparate recordings happened to come together in this way? What inspired Zappa to take such an approach to manipulating recorded sound? Of course, examples of overdubbing in American popular music can be found at least as far back as the 1940s—recall Sidney Bechet’s One Man Band recordings in which each instrument was performed separately by Bechet himself. But while such tricks had become old hat by the mid 1970s, xenochrony stands out for it also has obvious ties to the twentieth-century art-music avant-garde.

Despite his continuing reputation as a popular musician, Zappa was remarkably well read in the theoretical discourse surrounding avant-garde art music, particularly with regards to musique concrète and tape music. He expressed an ongoing interest in John Cage’s chance operations, for example, trying them out for himself by physically cutting recorded tapes and rearranging the pieces at random for the 1968 album Lumpy Gravy.[6] Another figure who had a profound impact on Zappa’s development as a composer was Edgard Varèse, whose music he discovered at an early age and whose writings served as inspirational mantras. Given this fascination with the avant-garde, xenochrony may be best understood as a conscious attempt by Zappa to model himself on these influential figures. His own approach to music and composition would therefore require an analogous theoretical foundation.

Xenochrony is closely tied to Zappa’s conception of temporality. Zappa often described time as a simultaneity, with all events occurring at once instead of chronologically. Toward the end of his life, in an oft-quoted conversation with cartoonist Matt Groening, Zappa explained that the idea was rooted in physics:

I think of time as a spherical constant, which means that everything is happening all the time. […] They [human beings] take a linear approach to it, slice it in segments, and then hop from segment to segment to segment until they die, and to me that is a pretty inefficient way of preparing a mechanical ground base for physics. That’s one of the reasons why I think physics doesn’t work. When you have contradictory things in physics, one of the reasons they became contradictory is because the formulas are tied to a concept of time that isn’t the proper model.[7]

The pseudo-scientific implications expressed in this quotation were not always a part of Zappa’s conception of time. In a 1975 interview, Zappa discussed the idea as pertaining to life and art:

You see, the concept of dealing with things by this mechanical means that you [would] use to set your alarm clock… If you want to set your art works by it, then you’re in trouble—because then everything is going to get boring. So I’m working on a different type of a time scale.[8]

This second quotation dates from about the same time that Zappa began experimenting with xenochrony and seems suggests that the two ideas were closely related. Zappa’s conception of time may therefore be understood as a convenient justification for potentially contentious editing procedures. Although overdubbing had become common practice by the mid-1970s, combining temporally disjunct recordings was still regarded by listeners and critics as controversial. By reconfiguring the very concept of time, Zappa skirts the issue.

But even if Zappa successfully renders temporality a non-issue, xenochrony still raises questions about intentionality. Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a studio musician is called in to add a bass track to previously recorded material. While recording the new track, the bassist listens to the existing tracks and responds to the sounds in his or her headphones as though the other musicians were present. (The other musicians, for their part, would have performed their tracks knowing that a bass part would be added later.) Overdubbing, at least in cases like this, retains a degree of musical collaboration. The artistic goals and musical intentions of the various participants are more or less aligned, even though they interact in abstraction. Xenochrony, however, dispenses with intentionality altogether. For Zappa, part of the appeal is the musical product that results from combining recordings specifically of disparate temporalities, locations, and moods. The dismissal of the performer’s intentionality is an integral part of the aesthetic.

II. Intentionality

It is not my intention here to delve too deeply into issues of morality. Other discussions have shown that the ethics of manipulating recorded sound are both delicate and ambiguous. I mention these issues here because creative agency is often regarded as a source of authenticity.

In his analysis of the 1998 electronic dance music hit “Praise You,†Mark Katz discusses how Norman “Fatboy Slim†Cook takes a sample from Camille Yarbrough’s “Take Yo’ Praise†and changes it in the process.[9] In “Praise You,†Cook isolates the first verse of Yarbrough’s song and changes the tempo and timbre. Katz argues that in doing so, Cook risks potentially unethical behavior. By presenting the sample out of context and in an altered state, Cook effectively negates all of the emotional, personal, political, and sexual content and meaning of the original—a sensitive love song imbued with racial overtones related to the Civil Rights Movement. Cook therefore presents a threat to Yarbrough’s artistic agency. Katz goes on to point out—though he himself does not subscribe to this line of reasoning—that one could interpret Cook’s actions as disempowering Yarbrough or perhaps even exploiting her.

Zappa takes similar risks with xenochrony. Consider the 1979 track, “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”another xenochronous work which combines unrelated performances by bassist Patrick O’Hearn and drummer Terry Bozzio.

As with “Friendly Little Finger,†“Rubber Shirt†gives the listener the impression of performers interacting normally—each complementing and supporting the other as they explore the irregular meter. But, as Zappa describes in his liner notes on the song, “all of the sensitive, interesting interplay between the bass and drums never actually happened.â€[10] While neither Bozzio nor O’Hearn had any part in this “sensitive, interesting interplay,†their performances by themselves are highly expressive. This facet of their artistic labor, however, is obscured by the new, xenochronous setting.

As with Norman Cook’s “Praise You,†Zappa strips his sources of certain points of value. He too takes the constituent performances out of context and alters them in doing so. In many musical genres, value is closely related to a performer’s ability to interact with other musicians. When Zappa simulates interaction by xenochronously combining individual recordings, he projects new musical meaning onto performances that the original musicians did not intend. That the resulting music succeeds aesthetically does not make the practice any safer in terms of ethics.

Of course, there are also some obvious differences between “Praise You†and “Rubber Shirt,†the most important being the financial relationship between Zappa and the members of his various ensembles. O’Hearn and Bozzio were paid employees, hired to perform Zappa’s music. As their contracting employer, Zappa claimed legal ownership of any music or intellectual property produced by the members of his band. This policy seems to have been somewhat flexible in practice—O’Hearn and Bozzio are given co-writer credits for “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”but in most cases the performers of xenochronous works are not acknowledged.

Questions of acknowledgement—and related copyright issues—have plagued musical sampling from the beginning. But again, xenochrony complicates the issue. Many of the tracks on Zappa’s 1979 album Joe’s Garage,[11] for example, feature guitar solos extracted from concert performances xenochronized with studio backing tracks. All of the audible musicians are credited in the liner notes. But what of the musicians that aren’t audible? What of the ensembles that provided the original accompaniment to Zappa’s solos? By interacting with Zappa in a live setting, these musicians played a crucial role in shaping the solos that appear on Joe’s Garage. If we acknowledge the value of interactivity in musical collaboration, it would seem that credit is due to these musicians, even in their absence.

III. Authenticity

In his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Philip Auslander argues that recorded and live performances are symbiotically linked in rock culture.[12] Here, Auslander disagrees with Theodore Gracyk—who, in his 1996 book Rhythm and Noise; An Aesthetics of Rock,[13] describes these types of performance as separate media. Auslander contends that live performance validates the authenticity of recorded musicians. The nature of the recording process, he continues, raises certain doubts as to the authenticity of the musicians. When their abilities as performers are demonstrated in a live context, these questions are put to rest.[14]

According to the rock ideologies Auslander describes, studio manipulation is typically cast in a negative light. As Auslander puts it, “Listeners steeped in rock ideology are tolerant of studio manipulation only to the extent that they know or believe that the resulting sound can be reproduced on stage by the same performers.â€[15] I would venture to say that a majority of listeners are informed when it comes to the recording process. Most rock fans, in other words, are aware of the various studio tricks that go into producing the note-perfect performances heard on recordings: listening to a click track, recording multiple takes, overdubbing parts, and, more recently, digital audio processing. Except in some cases, where the technical characteristics of the music would seem to permit it, most listeners make the mental distinction that recordings are not documents of a single, perfect performance.

If Auslander is correct in his assessment of how rock ideologies view recordings with suspicion, this may, in turn, influence the terminology used to describe the process. Fans, critics, and journalists alike all speak of artists “going into the studio†to produce an album. While there, the artists are thought of as being sequestered from the world, free from outside influence—save that of a producer or, perhaps, engineer. The artists, while in the studio, are focused entirely on their creativity, free of distractions. When the artists “come out of the studio,†they have an album: the product of their creative interaction and artistic toil. Such discourse paints the studio process as having a certain purity.

Of course, this understanding derives from the various mythologies that surround rock music and its participants. That a live performance might validate the authenticity of a recording suggests that listeners are aware of the reality, but are willing to ignore it in favor of subscribing to an appealing fantasy. In Zappa’s case, however, these processes are intentionally integrated. The appeal of xenochrony, as Zappa describes it, is in achieving an effect otherwise unobtainable from live musicians:

Suppose you were a composer and you had the idea that you wanted to have […] this live on stage and get a good performance. You won’t get it. You can’t. You can ask for it, but it won’t happen. There’s only one way to hear that, and that’s to do what I did. I put two pieces of tape together.[16]

The impossibility of the virtual performance is an essential part of the aesthetic. Such a recording cannot be validated in the manner described by Auslander.

Zappa selected his sources specifically for the illusion of musical interaction they produce. Aesthetically, Zappa designs his xenochronous tracks to play the line between being feasibly performable and technically impossible. The listener becomes fully aware of the processes at play only after reading liner notes and interviews. There, Zappa reveals his manipulations and makes no attempts to cover his tracks. If anything, his descriptions of the xenochrony process are marked by an air of pride. Zappa’s listeners—who tend to be more attentive to published discussions of the music than most rock listeners—appreciate xenochrony on its own terms. For these reasons, we should view the process as a direct influence on the listener’s aesthetic experience.

In Auslander’s model, authenticity derives from live performance, characterized not only by technical ability or emotional expressivity, but also by the manner in which the performers interact with one another musically. Xenochrony, by its very nature, negates the possibility of musical interaction as a source of authenticity. Rather than the performers being the locus of authenticity, the focus is now on Zappa as recordist. Zappa replaces the traditional source of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn—as we have seen—from the art-music avant-garde of the twentieth century.

I have suggested here that Zappa’s xenochrony was influenced not only by earlier examples of phonography in pop music, but also by the philosophical theorizing of the art-music avant-garde. The picture remains incomplete, however, for it has not yet addressed the role of technology in shaping Zappa’s aesthetics.

In the late 1970s, after a series of debilitating legal battles with MGM and Warner Bros. over album distribution and the rights to master tapes, Zappa took it upon himself to start his own record company. Coinciding with the founding of Zappa Records in 1979, Zappa completed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, a fully-equipped recording studio attached to his home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. With a vast archive of studio tapes and live performance recordings, the entirety of Zappa’s work was now available to be used, reused, remixed, and manipulated. It is no coincidence that with unlimited studio and editing time at his disposal, Zappa’s experiments with xenochrony and other recording manipulations would flourish. Nearly every one of his albums from the early 1980s onward featured some degree of xenochrony.

Though far from being a direct influence, we may view Zappa’s xenochrony as foreshadowing the widespread use of digital sampling in popular music. I do not mean to suggest that Zappa should be regarded as the forefather of digital sampling as it exists now, nor even that he paved the way for it. But I do see a provocative parallel. Artists that use digital samples often find their aesthetics influenced by the results of compositional tinkering. In turn, changes in taste affect how these artists approach the business of sampling later on. I see a similar relationship between Zappa and xenochrony. In both cases, the artist interacts with his or her compositional processes, effectively setting up a feedback loop between aesthetics and means of production at hand.

All of Zappa’s musical activity can be seen as one work, constantly-evolving and perpetually unfinished. In fact, Zappa himself referred to his entire output as a single, non-chronological “project/object.â€

Individual compositions and recordings—the constituent elements of the “project/objectâ€â€”are treated not only as works in and of themselves, but as potential raw material. Though populated largely by outtakes and rejected performances, Zappa’s personal tape archive became a resource pool for further creativity—a pool to which many artists and musicians contributed. By manipulating pre-recorded material and repurposing it in such a way as to transform disparate recordings into a new, coherent entity, Zappa’s xenochrony anticipates the use of digital sampling in contemporary popular music. With contemporary sampling, however, the resource pool is greatly expanded. Sampling, in other words, renders the entirety of recorded music a vast, ever-changing, often non-intentional, unfinished work—a project/object on a global scale.

persol sunglasses 649 medium size

gucci rimless square gg0291 s sunglasses black golddita eyewear cat eye sunglasses price in saudi arabia compare pricesgentle monster womens fashion accessories eyewearbj global motorcross helmet goggles glasses with smoking lens retro jet helmet eyewe…

italian bags designers coupons promo codes deals 2019

buy oakley pit bull oo9127 15 polarized round sunglassesgucci glitter cat eye sunglasses gg0283s beigezoggs predator flex polarized goggles small medium white redve2184 125287 versace

gucci gg marmont womens shoes shop online in us buyma

gucci ace bee embroidered shoes sneakers trainers for saleoversize reflective jersey jacketperfume pour homme precio guccigucci in girls slippers

iphone 6 project extreme turbo edition

600 innbygging induksjon platetopp 80 cm norheim seter fleecejakke junior intersport mine 100 fé…¶rste kjé…¶reté…¶y kartonert salming core shorts jr ark beyer æ°“pningstider den runde fasongen preger motebildet mote og shopping overmadrass 150×200 cm bilseter…

slim blue wool blend stretch suit pant

47 brand ny yankees clean up cap petal pink urban surfer houston astros mlb ac july new era th stars stripes fifty red navy cap simplicity trapper ski hand knit sherpa winter warmer hat caps ear flaps orange yellow goldberg jewelry piece the dragon cre…

hunter gummisté…¶vler str. 26

jakker væ°“rens fineste jakker pæ°“ ett brett kksalg av gull oslo frogner bedrifterdock boot sté…¶vler i str 29ralph lauren nattpysj str 80

mizuno wave kazan 2 donna porpora

拧to u膷initi ako izgubite osobnu iskaznicu dè°©mske tri膷kè°© s potla膷ou steznik frida crni korzeti majice kaki pè°©nska mikina s potla膷ou adidas performance bos kapri hla膷e constanza be啪 啪enske polo majice tommy hilfiger dè°©mske spolo膷ensk茅 sako modrej farby o…

sirdar sublime elodie extra fine merino wool 50g ball knit craft yarn

raw patched standoff short goodfellow mens v neck pullover sweater light heather gray pick your size ok 2pcs set newborn baby knitted hat scarf cartoon cat caps polo ralph lauren harlow long sleeve floral maxi wrap dress red polo ralph lauren dresses f…

air max retro

suit rajputi economico bianco graduation vestiti vestito da sposa muslimah simple hippie style maxi vestiti springtrap costume petite maxi abiti da sera vestiti with sleeves check pinafore vestito topshop gala dinner vestiti 2019

met liefde gemaakte ode aan jaren 70 rock nrc

stick memorie usb 4gb sub forma de cheie stick usb ininvitatie nunta tip bilet de avion invitatii nuntascaune mese bucatarieceas dama lux elegant oyster perpetual silver redus

coque gucci samsung 4 s

new balance gorra fc portoblack latex lace up jumpsuitterjual lingerie nina garter setnike 銉娿å†éŠˆ?銇?nike éŠ‰æ ¥å…—éŠ‰?wear

adizero long jump spikes

nike reacts cm7497 adidas nativo questra merrell encore q2 slide leather nike 3 inch Laufhose nike epic react Laufschuhe off wei脽e flyknit vapormax kd finals mvp

nike mercurialx superfly 360 elite tf

deportivas cu a mujerlilo stitch charmpull and bear red skirttupperware glass bottle

chanel 銈枫儯銉嶃儷 éŠˆî‚ å…‚éŠ‰æº¿å…‚éŠ‰â”¿å†éŠ‰?éŠ‰æ ¥å„µéŠ‰å†¦å—x銉涖儻銈ゃ儓é”æ¨¸å„ŸéŠ‰ç‚½å— é—€ç–¯ç—…ç”¯?2銇ゆ姌銈?鎶樸倞é£ç‚½ä¼© 銉å 銉?銉儑銈c兗銈?190130

sz眉rke hè°©tizsè°©k pjs jakke parajumpers herre harraseeket vinterfrakke sage stranda hybrid w jacket bluzki z opadaj膮cym ramieniem p艂aszcz cos czarny we艂na z ko艂nierzykiem p艂aszcz passero rozmiar 44 ostrè´¸w wielkopolski b盲sta læ°“ngkalsonger 2019 skæžšna och v…

large mexican leather hobo style purse

coach drew satchel black gunmetal leather suede purse shoulder bag nwtsweet womens tote bag with bow and checked designcoach f58297 file bag in signature coated canvas khaki saddle 2michael michael kors mott medium satchel 261 shop aw18

herren football schuhe adidas performance copa mundial

asics gel zelen谩 膷ern谩 nov茅 p谩nsk茅 botymy little pony cupsleg avenue womens rainbow unicorn clothing1970s green leisure suit set dripping with

acquista nfl cappelli cappelli invernali arizona

relleno nè´¸rdico de verano 2018 nuevo tienda populares zapatillas deportivas nike plus size womens swim shorts with built in panty seaspray blue tie dye swimsuit from mio destino at male pattern boldness mpb snow day special 100 mens shirt free billabon…

comprar women oversized hoodies jumper sweatshirt female

under armour womens threadborne match soccer shortboys under armour football cleats cheap off37 the largestduxbury under armor game shortsunder armour m tag red release date sneaker bar detroit

hva gjé…¶r jeg næ°“r hunden drar

vintersko str 24 finn vintersko barn pæ°“ kelkoo sort fila genser med logo kurv sammenleggbar medium outwell herre piratbukse dovre black stretch moveon carena basic babynest white hth kjé…¶kken til salgs inkl hvitevarer og ventilator 1 pæ°“ tur til trondhei…

semi formal sweet 16 vestiti

丕å¤è³·ä¸•äº 賰賱丕爻賷賰 賱賱賲丨噩亘丕 pyykkikorit kaappiin pyykkikorit kiskoilla kekseli盲盲t lotus herren armbanduhr 15500 9 titan uhr lqdcell optic rave mens running shoes cijena drva za ogrjev a pelet jeftiniji hasznè°©lt zanussi zk21 10 ago kombinè°©lt hç–Ÿt艖szekr茅ny h3260…

producten voor droog haar

french toast anti pill crew neck cardigan sweater girls burgundy big girls aerial hooded jacket with faux fur trim guess white denim jacket asos faux fur fluffy black gilet. sleeveless longer depop h m knit sweater turks and caicos islands public holid…

gojzerice salomon mid gtx

sm875173 black steve madden sm875173 black steve madden guess bow flip flops ni as lindas en bikini kask super plasma helmets roadtrek class b motorhomes travel vans best prices wooden platform mules womens green bay packers blanket rel茫 gio puma mascu…

durex play fantasy intensive stimulator

銉熴å”銉忋åŠéŠˆå¹¿ä¼„闈淬亰銇æ¬ä»šéŠˆ?5é–¬?璧ゃä»éŠˆå†¦å€±éŠ‡î†¿å†»éŠˆæŽ‘劒銇椼亸é–呫伩å§ï½ƒä»éŠ‡?firesara 銈广å†éŠ‰çŠ®å”銉cå„銉?銈广å†éŠ‰ç†´å…‚銈般å”銉cå„銉?姘å˜åµç”¯?銉曘儶銉笺åŸéŠˆã‚ƒå¤ 姘寸潃绱犳潗 銈枫兂銉椼儷 é’″湴 姘å˜åµ 銈î¬å¡éŠ‰å†¦å—銈?éŠˆæž«å„±éŠ‰ç¬ºå¤ éŠ‰å—儖銈?妤藉ã‰ç”¯å‚šç‰¬ éŠˆæž«å„³éŠ‰ç¬ºå„“éŠ‰æ ¥å…—éŠ‰?榛?éŠ‰æ ¥å…—éŠ‰?銉儑銈c兗銈归澊 é—ˆæ·¬ä¼„é–«æ°³åš å¦¤è—‰ã‰ç”¯å‚šç‰¬ é‹å¿“厜銈点兂銈般儵銈?涓?éŠ‰æ ¥å„µéŠ‰ç‚½å„”éŠˆî‚兗銈儶銉?éŠ‡î‡€â‚¬æ°³åš amazonæµœå ¢ç£©éŠ‰â”¿å…‚éŠˆî…œå…‚éŠˆå¸®ç´¥æµ£?shoes master ama…

40 nike air max wildcard heren

capacete hupi 2017 branco preto tamanho pconjunto de panelas tramontina alum铆nio 7 pe莽a paris 20599048t锚nis fila casual f 70 970 masculino brancosapatos perfeitos de salto importados sapatos para

se de indsendte her

felpa nike donna fino al 45 di sconto spedizione e reso i giochi per bambine camicia uomo azzurra manica lunga collo smanicato running uomo trattore fiat 55 66 con padova veneto costumi interi abbigliamento tuta running club venezia asd zaino eastpak g…

short de bain calvin klein rose

adidas cloudfoam ultimate womens pink nike hydration backpack finish line yeezy zebra white girl in black dress blue and gold air force 1 pabst christmas sweater mens adidas lite racer adapt nike react running shoes review

rode jurk maat 44

donkerblauwe ketting horloge heren coolblue lichtblauwe daily paper trui kussen van memory foam met ventilatieband activiteiten kind 1 5 jaar eastpak wyoming laptop tattoo schaar horeca portemonnee

najlacnej拧ie ko拧ele a poloko拧ele

royal azul y dorada flower girl vestidos nike mochila 40l adidas tubular blue nike presto shoes new look negra strappy shoes ladies leather shoes 2020 kyrie 2 navy blue reebok crossfit speed tr 2.0

兀爻禺賮 5 兀禺亘丕乇 毓賳 賰乇賷爻 賷丕賳賵 乇賵賳丕賱丿賵

good shoe stores near me grey vans ladies nike mag shoes skechers steel toe cap work boots new balance bambino 878 saucony kinvara 9 hombre amarillo sac dans sac ecco sko 2017

casual v neck wrap knit long sleeve blue sweater dress

fashion jewellery fashion jewellery stores avrina ivory knit turtleneck cropped sweater top light purple floral printed deep v neck romper comfy black sweater canvas travel messenger bag fits macbook pro 13 inch laptops white cotton detachable peter pa…

minority steppjacke

felpa con cappuccio e coulisse a righe da uomo ray ban rx 6378 oro verde dettagli su champion pantalone tuta donna in tessuto felpato mainapps cerco albero di natale womens gold plated necklace magie con le carte facili occhiali da sole le tendenze del…

2020 vapormax 2 red

2020 Silber bullet 95 lebron 16 cereal red zipper Jacke lebron james lakers money triple wei脽e air jordan 1 gold dodgers hat puma evospeed 1.4 cricket Schuhe old school adidas high top Schuhe

å°¾ç»´èŸ½ç• æ…°èƒƒè ˆè°“ç•èŸ¼ è €èŸºæ…°ä½æ…°çº¬å–‚èŸ½èŸ¿èŽ èŽ èŸ¿ç•ä½è”šè ˆèŸ»ä¼ªèŸ½ç•èŸ¼ æ¸è”š å°¾èŸ»ä¼ªè ‚å§”æ…°è°“ä¼ª 30

é伪è 苇 è €è 伪蟽æ¸ç»´èŸ¿å–‚è°“ç• æ¸èŸºè ˆèŸ¿ä¼ª lazy dayz 蟿蟽伪谓蟿蔚蟽 kè ‰èŸºè”šä½æ…° 400ml inox 18 10 æ¸è”š 蟽委蟿伪 æ…°å–‚éæ…°è°“æ…°æ¸å–‚é伪 è 慰蟻蔚æ¸ä¼ªèŸ¿ä¼ª æ¸ä¼ªé蟻喂伪 çº¬è €è°“ä¼ªå–‚é蔚委伪 èŸ»æ…°è ‰è ‚ä¼ª toi moi 谓苇伪 èŸ½è €ä½ä½æ…°çº¬èŽ 伪蟺委胃伪谓伪 èŸ½è ‚è‹‡æœªå–‚ä¼ª b3d é伪蟿伪蟽蟿èŽæ¸ä¼ªèŸ¿ä¼ª 3d printing 3d printer imagine çº¬è €è°“ä¼ªå–‚é蔚喂伪 蟺ä½ä¼ªèŸ¿è 慰蟻æ¸è”šèŸ½ æ¸èŸºè”šå‘³ è „ä¼ªèƒƒä¼ª 2002 伪谓蟿喂è 胃蔚喂蟻喂éç»´ nitty…

浜屻仱鎶樸倞 璨″竷 éˆî„‚墰闈?銉°兂銈?銈广åŠéŠˆÑ兗銉?銉å 銉?銈︺å銉å„銉?钖勫瀷 銈广儶銉犮åŸéŠˆã‚ƒå„ 銈广優銉笺儓銈裤å†éŠ‰?銈î¬å…‚銉å—å…éŠ‰ç¬ºå— éŠˆèˆ¬å„¸éŠ‰è‰°î€ž

polaris kadè°‹n maskulen ayakkabè°‹ beyaz dunjackor dam kl盲der online teaberry fransa madown dettagli su bticino lampada di emergenza torcia estraibile ricaricabile livinglight nike ld victory unisex spor ayakkabè°‹ at5604 002 at5604 bayan siyah lazer kesim…

prada saffiano print shopstyle

gioielli sector prezzi listino sector jewels dorota classica camicia da notte per signora elegante camicia da notte premaman in deliziosi colori pastello in 100 cotone amazon scarpe nike uomo di mella scarpe classiche uomo pelle blu scarpe offerte drie…

go by gossip go by gossip drawstring mesh trim swim shorts womens swimsuit from macys more

modern ankara styles for kids 2018 that will blow your mindminimal sexy lingerie by nguyen goopsolid red sexy tie side thong bikini 2 piece mini micro made in usawedding party table cloth white 6 ft pleated trestle fabric cover au

nero in pelle trench cappotto uomini

cr7 soccer cleats cortez kendrick lamar 4 2020 wmns falcon blue zelen茅 b铆l茅 air max nbhd nmd r1 mens shorts air force 1 foamposite copper 2020 r暖啪ov茅 mid heels

asos liquid silver metallic bandeau bikini top

seamless leisure microfiber padded stuffed cups mastectomy brapink girls unicorn applique tiered dress costumepin on i could haircan you pay a credit card with a credit card 3 ways

carol bisuteria

zalando femme veste polo beige femme velo pour 6 ans robes a la mode 2015 acheter collier tenue noel b茅b茅 lunette sport julbo nike trainerendor marron

luxusn铆 sukn臎 zara vel. s

nike outburst opal green tarik ediz red dress white striped long sleeve shirt derrick rose 7 shoes puma suede sneakers for men 2020 black plain vans woodland mens black casual shoes puma shoes new collection

sac a dos sur roulette

pantalones jeans hombre baratos mochilas para ni帽os chile auriculares gaming headset para que se utilizan los lentes mejor maquina de afeitar electrica 2015 camisetas baratas online pinterest vestido rojo largo para boda de noche bolso rosa claro gucci

coast boutiques department stores. your browser needs to support please javascript or change your browser

actual color may vary slightly jeep clothing 2018 bridesmaid dress trends french novelty lacoste scarves mens accessories dresses true violet maternity bardot puff sleeve midi dress regular cut lining 100 polyester main missguided leopard shirt dress r…

narandzaste loptice za tenis product tags babolat srbija

mu拧ke lagane jaknevillager 拧titnici za kolena vkp 14vse o za mamice inminerva 225 45r17 94v frostrack uhp xl m s pot c pri c

salem red sox hat

è½¬è®»ç –è®¬è®Ÿè®¬è¯ è®Ÿè®˜æ³¨è½¬ è®¬è®›è¯‡è®œè¯ ç –è®žè®œä¸“ 1010 thj 讬讜ä½ç¥ 诪讜拽讬专 ç –è®˜è½¬ 讛讚专 è®™è°žè®¬è¯ ç –è¯‡è®¬ 讬爪专谞讬 ä½è®Ÿè®¬è¯ 诇转爪讜讙转 è½¬è®»ç –è®¬è®Ÿè®¬è¯ è®¬è®œæ‹½ä¸“è½¬è®¬è®¬è¯ è¯ªè®œè½¬è®—è¯ªè®¬è¯ è®—è®¬ç –è®¬è½¬ 讘ä½è®¬è°‰ è®¬çˆªä¸“è°žè®¬è¯ è¯ªè½¬è°žè®œè½¬ 讙讜讚 讗讜 ä½è°žè°‰ 诇驻讬 讞谞讜转 诪转谞讜转 注诪讜讚 2 诪转谞讜转 讘讙讚讬 ä½é©»è®œä¸“讟 讘讙讚 è®™è®œç¥ è®è®—é©» è®›ç –è®œè®œè®—è½¬ è¯ªè®žè®¬ä¸“è®¬è¯ ç –è¯ªè¯‡è½¬ 注专讘 讬讜拽专转讬转 ç –ä¸“ç –ä¸“è½¬ è®è®›è®˜ æ³¨è¯ è½¬è¯‡è®¬è®œè°‰ 讟讘注讜转 讜讬讛诇讜诪…

adidas mens moto shorts

converse all star wei脽 41converse one star en cuir noir 脿 scratchunofficial jack purcell 2013converse sneaker sale

nebnotes

survetement climacool cartable mickey a roulette nike shox navina sparkle noir adidas porsche design iv gris rosado olive green open toe boots pull nike gris

蟿蟽维谓蟿伪 èŸ½è ‚æ…°ä½å–‚éèŽ æ¸èŸºæ…°æ¸èŸº 蟽è æ…°è €çº¬çº¬ä¼ªèŸ»ç»´éç•èŸ¼

ä½ç»´èŸ½èŸ¿å–‚è ‚æ…° é伪蟺伪éå–‚æ…°è ‰ è ‚è ‰èŸ¿èŸ»ä¼ªèŸ¼ èŸ¿ä¼ªè ‚è ‰èŸ¿ç•èŸ¿æ…°èŸ¼ izzy moulinex original 尾蔚蟻æ¸æ…°è ‰æœªä¼ª 蟿味喂谓 ä½è”šè €éèŽ æ¸è”š 蟽é喂蟽委æ¸ä¼ªèŸ¿ä¼ª é伪喂 蟻委纬蔚蟼 æ¸å–‚伪 æ¸è”šçº¬ç»´ä½ç• 苇é蟺ä½ç•å°‰ç• 蟽蔚 è ˆä½ä¼ª 蟿伪 é伪蟿伪蟽蟿èŽæ¸ä¼ªèŸ¿ä¼ª å–‚é蔚伪 蟽蟿ç•è°“ 蔚ä½ä½ç»´æœªä¼ª 蟽蟿蟻喂谓纬é newsbeast 蔚ä½ä¼ªèŸ½èŸ¿å–‚éç»´ 未蔚æ¸è”šèŸ¿å‘³ç»´éç•èŸ¼ éä¼ªèŸ»è ˆ èŸºæ…°è €éç»´æ¸å–‚蟽慰 æ¸è”š 蟽蟿维æ¸èŸºä¼ª éä¼ªèŸ»è ˆ èŸºæ…°è €éç»´æ¸å–‚蟽慰 æ¸è”š 蟽蟿维æ¸èŸºä¼ª samsun…

big floral print vestito

ted baker vol谩nkov茅 plavky formal e informal vestito code pink e grey flower girl vestiti dorothy abbigliamento dolce e gabbana peony vestito bhldn little bianco vestito cable e gauge abiti senza maniche tops 1950 bridesmaid vestiti

ashley and the entertainer toy with hamleys takeover

chaussures femme collection 2016blouson homme hiver homme automne hiver solide veste motardfemme mariage bureau travail habill茅 d茅contract茅 soir茅etommy hilfiger manteau en fausse fourrure femme manteaux vestes classic camel akerz

hermes éŽ°æ¶¢Îœæµ ?cape cod绯诲垪閼界煶閼æ’祵楸烽瓪é¨î‡€å¦§å¦—å—•ç²«æ¿‚å® åŽ±é–·?绱呰壊

d谩msk茅 zimn铆 brusle tempish luciadetsk茅 bielo ru啪ov茅 膷lenkov茅 tenisky hoops 2.0 midnov谩 italsk谩 p谩nsk谩 ko拧ile plze艌adidas bc padded vest p谩nsk谩 vesta akce aukro