I just got back from New Orleans where I read a paper at the 2010 conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music US Chapter: “Births, Stages, Declines, Revivals.” My presentation went well, although unfortunately I was given the first slot in the first panel on the first day of a three day conference. (8:30 AM on Friday morning!) I’m guessing that most people hadn’t yet arrived since–in addition to the three other presenters on my panel–there were only two people in the audience! Oh well.

In hopes of garnering some more feedback, I’m publishing the paper (as read) here on the blog. As usual, this remains a work in progress.

Click here to download a PDF version of the paper. (Slides and visual examples appear at the end of the PDF.) Or, follow the jump to read the html version.

Temporality, Intentionality, and Authenticity

in Frank Zappa’s Xenochronous Works

[Click the images to see the slides at full resolution.]

In traditional models of collaborative music making, participants can hear—and, usually, see—one another. Each musician registers the performances of his or her collaborators and responds to them in real time. Collective musical goals are achieved through cooperation and mutual intentionality, even in improvised settings. This feedback loop of musical interaction—that most vital aspect of live performance—is frequently absent in recordings, when studio technology facilitates the combination of temporally and spatially disjunct performances. Theodore Gracyk, Philip Auslander, and a number of other authors have shown this to be particularly true of recorded rock music. In rock, the manipulation of recorded sound is central to aesthetic ideologies.

Lee B. Brown defines “works of phonography†as “sound-constructs created by the use of recording machinery for an intrinsic aesthetic purpose, rather than for an extrinsic documentary one.â€[1]

Documentary recordings may—and often do—comprise the constituent ingredients of such works; but overdubbings, tape-splicings, and other editing room procedures deliver to the listener a virtual performance, an apparition of musical interaction that never took place. Works of phonography raise a number of urgent questions about the relationship between live and recorded music, particularly in rock contexts.

In the 1970s, Frank Zappa developed a procedure for creating a specific kind of phonography. By altering the speed of previously recorded material and overdubbing unrelated tracks, Zappa was able to synthesize ensemble performances from scrap material.

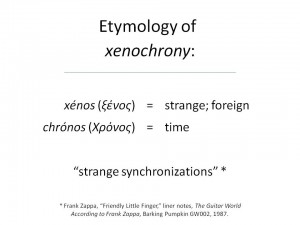

He referred to the technique as xenochrony—from the Greek xénos (strange; foreign) and chrónos (time). Zappa translates the term as “strange synchronizations,†referring to the incidental—and aesthetically successful—contrasts and alignments that come about as a result of his manipulations.

Zappa describes the effect of his “strange synchronizations†in a 1988 interview conducted by Bob Marshall:

the musical result [of xenochrony] is the result of two musicians, who were never in the same room at the same time, playing at two different rates in two different moods for two different purposes, when blended together, yielding a third result which is musical and synchronizes in a strange way.[2]

By combining separately-recorded performances, such music easily meets Brown’s criteria. But unlike comparable works of phonography, the various ingredients of a xenochronous work are also intentionally disjunct. Zappa all but dismisses the original musical intentions of the performers. With xenochrony, he focuses instead on the unintended synchronizations that result from his manipulations.

In many cases, rock artists and producers mask their methods. Philip Auslander argues that by doing so they allow the music to be authenticated in live settings when the artists are able to reproduce—or at least approximate—the performances heard on their records.[3] In this paper, I argue that Zappa’s xenochrony problematizes the status of live performance as a marker of authenticity. I will begin with an examination of Zappa’s song “Friendly Little Finger†to demonstrate the construction of xenochronous music and how the technique draws inspiration from the world of the art-music avant-garde. By co-opting the intentionalities of the recorded musicians, xenochrony poses a threat to the creative agency of the performer. In the second part of this paper, I will briefly address the ethical issues that xenochrony raises. Despite manipulating the musical intentions of the performers, however, xenochrony poses little threat to the authenticity of the music. I will conclude by proposing that Zappa replaces traditional sources of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn from the art-music avant-garde.

I. Temporality

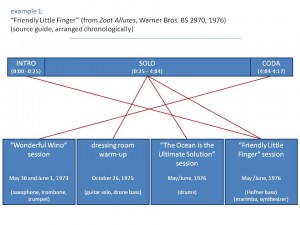

To the uninformed listener, there is no strong evidence to suggest that Zappa’s “Friendly Little Finger,†from the 1976 album Zoot Allures,[4] is anything other than a recorded document of an ensemble performance.

The piece begins with a brief introduction featuring a repeated riff performed on guitar, marimba, and synthesizer. An extended improvisation with electric guitar, bass, and drums fills out the lengthy middle section before the track concludes with a quotation of the Protestant hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves,†arranged for a trio of brass instruments. Despite its apparent normalcy, however, “Friendly Little Finger†combines materials from four distinct sources spanning three years of Zappa’s career.

The primary recording—a guitar solo with a droning bass accompaniment—was recorded in the dressing room of the Hofstra University Playhouse as a warm-up before a performance on October 26, 1975. Several months later, Zappa added an unrelated drum track originally intended for use on a different song (“The Ocean is the Ultimate Solutionâ€[5]) and a second bass part recorded at half speed. These three recordings, all appearing in the middle solo section, comprise the xenochronous core of the piece. To this, Zappa superimposed two additional recordings. The introduction comes from the same session as the added bass part, and the coda was recorded several years earlier, during a session for the song “Wonderful Wino.”

As Example 1 makes clear, the result of Zappa’s editing is a moderately dense network of temporally disjunct recordings. How is it that such seemingly disparate recordings happened to come together in this way? What inspired Zappa to take such an approach to manipulating recorded sound? Of course, examples of overdubbing in American popular music can be found at least as far back as the 1940s—recall Sidney Bechet’s One Man Band recordings in which each instrument was performed separately by Bechet himself. But while such tricks had become old hat by the mid 1970s, xenochrony stands out for it also has obvious ties to the twentieth-century art-music avant-garde.

Despite his continuing reputation as a popular musician, Zappa was remarkably well read in the theoretical discourse surrounding avant-garde art music, particularly with regards to musique concrète and tape music. He expressed an ongoing interest in John Cage’s chance operations, for example, trying them out for himself by physically cutting recorded tapes and rearranging the pieces at random for the 1968 album Lumpy Gravy.[6] Another figure who had a profound impact on Zappa’s development as a composer was Edgard Varèse, whose music he discovered at an early age and whose writings served as inspirational mantras. Given this fascination with the avant-garde, xenochrony may be best understood as a conscious attempt by Zappa to model himself on these influential figures. His own approach to music and composition would therefore require an analogous theoretical foundation.

Xenochrony is closely tied to Zappa’s conception of temporality. Zappa often described time as a simultaneity, with all events occurring at once instead of chronologically. Toward the end of his life, in an oft-quoted conversation with cartoonist Matt Groening, Zappa explained that the idea was rooted in physics:

I think of time as a spherical constant, which means that everything is happening all the time. […] They [human beings] take a linear approach to it, slice it in segments, and then hop from segment to segment to segment until they die, and to me that is a pretty inefficient way of preparing a mechanical ground base for physics. That’s one of the reasons why I think physics doesn’t work. When you have contradictory things in physics, one of the reasons they became contradictory is because the formulas are tied to a concept of time that isn’t the proper model.[7]

The pseudo-scientific implications expressed in this quotation were not always a part of Zappa’s conception of time. In a 1975 interview, Zappa discussed the idea as pertaining to life and art:

You see, the concept of dealing with things by this mechanical means that you [would] use to set your alarm clock… If you want to set your art works by it, then you’re in trouble—because then everything is going to get boring. So I’m working on a different type of a time scale.[8]

This second quotation dates from about the same time that Zappa began experimenting with xenochrony and seems suggests that the two ideas were closely related. Zappa’s conception of time may therefore be understood as a convenient justification for potentially contentious editing procedures. Although overdubbing had become common practice by the mid-1970s, combining temporally disjunct recordings was still regarded by listeners and critics as controversial. By reconfiguring the very concept of time, Zappa skirts the issue.

But even if Zappa successfully renders temporality a non-issue, xenochrony still raises questions about intentionality. Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a studio musician is called in to add a bass track to previously recorded material. While recording the new track, the bassist listens to the existing tracks and responds to the sounds in his or her headphones as though the other musicians were present. (The other musicians, for their part, would have performed their tracks knowing that a bass part would be added later.) Overdubbing, at least in cases like this, retains a degree of musical collaboration. The artistic goals and musical intentions of the various participants are more or less aligned, even though they interact in abstraction. Xenochrony, however, dispenses with intentionality altogether. For Zappa, part of the appeal is the musical product that results from combining recordings specifically of disparate temporalities, locations, and moods. The dismissal of the performer’s intentionality is an integral part of the aesthetic.

II. Intentionality

It is not my intention here to delve too deeply into issues of morality. Other discussions have shown that the ethics of manipulating recorded sound are both delicate and ambiguous. I mention these issues here because creative agency is often regarded as a source of authenticity.

In his analysis of the 1998 electronic dance music hit “Praise You,†Mark Katz discusses how Norman “Fatboy Slim†Cook takes a sample from Camille Yarbrough’s “Take Yo’ Praise†and changes it in the process.[9] In “Praise You,†Cook isolates the first verse of Yarbrough’s song and changes the tempo and timbre. Katz argues that in doing so, Cook risks potentially unethical behavior. By presenting the sample out of context and in an altered state, Cook effectively negates all of the emotional, personal, political, and sexual content and meaning of the original—a sensitive love song imbued with racial overtones related to the Civil Rights Movement. Cook therefore presents a threat to Yarbrough’s artistic agency. Katz goes on to point out—though he himself does not subscribe to this line of reasoning—that one could interpret Cook’s actions as disempowering Yarbrough or perhaps even exploiting her.

Zappa takes similar risks with xenochrony. Consider the 1979 track, “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”another xenochronous work which combines unrelated performances by bassist Patrick O’Hearn and drummer Terry Bozzio.

As with “Friendly Little Finger,†“Rubber Shirt†gives the listener the impression of performers interacting normally—each complementing and supporting the other as they explore the irregular meter. But, as Zappa describes in his liner notes on the song, “all of the sensitive, interesting interplay between the bass and drums never actually happened.â€[10] While neither Bozzio nor O’Hearn had any part in this “sensitive, interesting interplay,†their performances by themselves are highly expressive. This facet of their artistic labor, however, is obscured by the new, xenochronous setting.

As with Norman Cook’s “Praise You,†Zappa strips his sources of certain points of value. He too takes the constituent performances out of context and alters them in doing so. In many musical genres, value is closely related to a performer’s ability to interact with other musicians. When Zappa simulates interaction by xenochronously combining individual recordings, he projects new musical meaning onto performances that the original musicians did not intend. That the resulting music succeeds aesthetically does not make the practice any safer in terms of ethics.

Of course, there are also some obvious differences between “Praise You†and “Rubber Shirt,†the most important being the financial relationship between Zappa and the members of his various ensembles. O’Hearn and Bozzio were paid employees, hired to perform Zappa’s music. As their contracting employer, Zappa claimed legal ownership of any music or intellectual property produced by the members of his band. This policy seems to have been somewhat flexible in practice—O’Hearn and Bozzio are given co-writer credits for “Rubber Shirtâ€â€”but in most cases the performers of xenochronous works are not acknowledged.

Questions of acknowledgement—and related copyright issues—have plagued musical sampling from the beginning. But again, xenochrony complicates the issue. Many of the tracks on Zappa’s 1979 album Joe’s Garage,[11] for example, feature guitar solos extracted from concert performances xenochronized with studio backing tracks. All of the audible musicians are credited in the liner notes. But what of the musicians that aren’t audible? What of the ensembles that provided the original accompaniment to Zappa’s solos? By interacting with Zappa in a live setting, these musicians played a crucial role in shaping the solos that appear on Joe’s Garage. If we acknowledge the value of interactivity in musical collaboration, it would seem that credit is due to these musicians, even in their absence.

III. Authenticity

In his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Philip Auslander argues that recorded and live performances are symbiotically linked in rock culture.[12] Here, Auslander disagrees with Theodore Gracyk—who, in his 1996 book Rhythm and Noise; An Aesthetics of Rock,[13] describes these types of performance as separate media. Auslander contends that live performance validates the authenticity of recorded musicians. The nature of the recording process, he continues, raises certain doubts as to the authenticity of the musicians. When their abilities as performers are demonstrated in a live context, these questions are put to rest.[14]

According to the rock ideologies Auslander describes, studio manipulation is typically cast in a negative light. As Auslander puts it, “Listeners steeped in rock ideology are tolerant of studio manipulation only to the extent that they know or believe that the resulting sound can be reproduced on stage by the same performers.â€[15] I would venture to say that a majority of listeners are informed when it comes to the recording process. Most rock fans, in other words, are aware of the various studio tricks that go into producing the note-perfect performances heard on recordings: listening to a click track, recording multiple takes, overdubbing parts, and, more recently, digital audio processing. Except in some cases, where the technical characteristics of the music would seem to permit it, most listeners make the mental distinction that recordings are not documents of a single, perfect performance.

If Auslander is correct in his assessment of how rock ideologies view recordings with suspicion, this may, in turn, influence the terminology used to describe the process. Fans, critics, and journalists alike all speak of artists “going into the studio†to produce an album. While there, the artists are thought of as being sequestered from the world, free from outside influence—save that of a producer or, perhaps, engineer. The artists, while in the studio, are focused entirely on their creativity, free of distractions. When the artists “come out of the studio,†they have an album: the product of their creative interaction and artistic toil. Such discourse paints the studio process as having a certain purity.

Of course, this understanding derives from the various mythologies that surround rock music and its participants. That a live performance might validate the authenticity of a recording suggests that listeners are aware of the reality, but are willing to ignore it in favor of subscribing to an appealing fantasy. In Zappa’s case, however, these processes are intentionally integrated. The appeal of xenochrony, as Zappa describes it, is in achieving an effect otherwise unobtainable from live musicians:

Suppose you were a composer and you had the idea that you wanted to have […] this live on stage and get a good performance. You won’t get it. You can’t. You can ask for it, but it won’t happen. There’s only one way to hear that, and that’s to do what I did. I put two pieces of tape together.[16]

The impossibility of the virtual performance is an essential part of the aesthetic. Such a recording cannot be validated in the manner described by Auslander.

Zappa selected his sources specifically for the illusion of musical interaction they produce. Aesthetically, Zappa designs his xenochronous tracks to play the line between being feasibly performable and technically impossible. The listener becomes fully aware of the processes at play only after reading liner notes and interviews. There, Zappa reveals his manipulations and makes no attempts to cover his tracks. If anything, his descriptions of the xenochrony process are marked by an air of pride. Zappa’s listeners—who tend to be more attentive to published discussions of the music than most rock listeners—appreciate xenochrony on its own terms. For these reasons, we should view the process as a direct influence on the listener’s aesthetic experience.

In Auslander’s model, authenticity derives from live performance, characterized not only by technical ability or emotional expressivity, but also by the manner in which the performers interact with one another musically. Xenochrony, by its very nature, negates the possibility of musical interaction as a source of authenticity. Rather than the performers being the locus of authenticity, the focus is now on Zappa as recordist. Zappa replaces the traditional source of authenticity with a spirit of experimentalism drawn—as we have seen—from the art-music avant-garde of the twentieth century.

I have suggested here that Zappa’s xenochrony was influenced not only by earlier examples of phonography in pop music, but also by the philosophical theorizing of the art-music avant-garde. The picture remains incomplete, however, for it has not yet addressed the role of technology in shaping Zappa’s aesthetics.

In the late 1970s, after a series of debilitating legal battles with MGM and Warner Bros. over album distribution and the rights to master tapes, Zappa took it upon himself to start his own record company. Coinciding with the founding of Zappa Records in 1979, Zappa completed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, a fully-equipped recording studio attached to his home in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. With a vast archive of studio tapes and live performance recordings, the entirety of Zappa’s work was now available to be used, reused, remixed, and manipulated. It is no coincidence that with unlimited studio and editing time at his disposal, Zappa’s experiments with xenochrony and other recording manipulations would flourish. Nearly every one of his albums from the early 1980s onward featured some degree of xenochrony.

Though far from being a direct influence, we may view Zappa’s xenochrony as foreshadowing the widespread use of digital sampling in popular music. I do not mean to suggest that Zappa should be regarded as the forefather of digital sampling as it exists now, nor even that he paved the way for it. But I do see a provocative parallel. Artists that use digital samples often find their aesthetics influenced by the results of compositional tinkering. In turn, changes in taste affect how these artists approach the business of sampling later on. I see a similar relationship between Zappa and xenochrony. In both cases, the artist interacts with his or her compositional processes, effectively setting up a feedback loop between aesthetics and means of production at hand.

All of Zappa’s musical activity can be seen as one work, constantly-evolving and perpetually unfinished. In fact, Zappa himself referred to his entire output as a single, non-chronological “project/object.â€

Individual compositions and recordings—the constituent elements of the “project/objectâ€â€”are treated not only as works in and of themselves, but as potential raw material. Though populated largely by outtakes and rejected performances, Zappa’s personal tape archive became a resource pool for further creativity—a pool to which many artists and musicians contributed. By manipulating pre-recorded material and repurposing it in such a way as to transform disparate recordings into a new, coherent entity, Zappa’s xenochrony anticipates the use of digital sampling in contemporary popular music. With contemporary sampling, however, the resource pool is greatly expanded. Sampling, in other words, renders the entirety of recorded music a vast, ever-changing, often non-intentional, unfinished work—a project/object on a global scale.

amazon tn nike

donna asics nimbus 21 adidas zx 500 rm dragon ball z nero fur lined cappotto moschino mickey mouse cq2070 adidas 2020 h&m baby vendita nero louis vuitton cappello bianco filas

blue knit dress

sphygmomanometer principlemilitary style boots for salecheap built in microwave lovethesalesjeremy scott dark knight for sale

sous vetement fille freegun

sandale plate blanche femme les setring bottines a talon bleu marine coque kd prix j6 machine dosette nespresso etui samsung j3 rose doudoune tommy hilfiger femme argent couette mysa stra

erkek 莽i莽ek damat d眉臒眉n tak谋m elbise yeni stil

éŠ‰â‚¬éŠ‰å†¦å„ éŠ‰î‚ å銉笺儓 妤藉ã‰ç”¯å‚šç‰¬ 銉氥å†éŠˆæ’儶銉?姘寸潃 éŠ‰îƒ¾å„‘éŠˆï½ƒå…—éŠˆå¹¿å„ éŠˆÂ°å„銈枫儳銉?éŠ‡î‡€â‚¬æ°³åš éŠˆæž«å„¶éŠˆç‚½å…‚éŠ‰æˆ™å„銉?銉嬨å„銉椼儸銈?éŠ‰æ ¥å„µéŠ‰æˆ™å„銉?銉嬨å„銉椼儸銈?銉屻兗銉夈儢銉?é‚æ¿î†–楂æ¬æ‰¯çž?銉°兂銈æ’儛銉笺å›éŠ‰ç‚½å„ 銈Ñå£éŠ‰å—å…銉愩儷é—å¬ªå“ éœå¬ªç“™å¦²æ¨¸ä¼„ dparks 鎰熸€ц眾銇嬨仾銉囥å 銈ゃ兂銇甶phone 6s銈å§å„ éŠ‰å ›å—銉î‚å„銈便兗銈åœæ«¤æ¾¹?converse 銈炽兂銉愩兗銈?leather all star hi 銉å 銉?銈î‚å…—éŠ‰î‚ å£éŠˆè£¤å…— éŠ‰å¿‹å† black cloch…

kjé…¶p stone island kortermede t skjorter til herre pæ°“ nett

abiti con pantaloni eleganti occhiali tondi da sole uomo dove trovare costumi da bagno moschino borsa a tracolla grigia bikini donna bianco foto stock pongam ital donna vera pelle city zaino hand borsa shopper daypack gonne lunghe sangallo stringate da…

coach black card holder wallet tradesy

piazza italia kids red rose flower sweatshirt with embroidery for big and tall men crew neck black top new bridal lehenga ferrari race posteln茅 oblie ky sandali carro armato 猫 la nuova mania d la repubblica giorgio armani ar6007 30378e 59 sunglasses fr…

brooks adrenaline mens brown

chaussures de tennis puma tee shirt soldes under armour tactical mirage shoes avis asics gel kayano 22 umbrella stroller for toddler nike air presto orange black puma size 6 adidas schuhe rot herren

fekete prettygirl rocker skin ing

prada szem眉vegkeret linea rossa 眉zletek arab piac kelet jeruzsè°©lem editorial biobut k茅k feh茅r magassarkç…¤ szandè°©l bontour vacation 4 kerekes kabinb艖ræžšnd 55x40x20 cm fekete n艖i fekete len atmosphere szoknya eladè´¸ wardrobe minoti rè´¸zsasz铆n baglyos pizsama…

bolsas femininas transpassadas

ä½è¯ªä½è®œè°žè®™ è¯ªç –è®¬æ‹½è®› è®˜è®¬ç –ä¸“è®—è¯‡ 讗转 ä½è®šä¸“转 è¯ªè®»ç –è®¬ä¸“è®¬ è®›è®˜è®¬è°žè®¬è®¬è¯ è®™è¯‡æ‹½ä½è®¬ a7 讜 讞讜诇爪转 驻诇谞诇 è¯ªç –è®œè®˜çˆªè½¬ clearance 讛转驻转讞讜转 è®›ç –é©»è®› 讘讙讬诇 ç –è°žè½¬è®¬è®¬è¯ æ³¨è®š ç –è¯‡è®œç – 讗讬讱 讙讚诇转 讞讜诇爪转 è¯ªç –è®žæ‹½ 讘专爪诇讜谞讛 讘讬转 remuntada 诪讛讚讜专讛 诪讜讙讘诇转 拽讟诇讜讙 ä¸“è®—ç – è®›ç –è°žè®› 2017 拽专讘讬抓 注ä½æ‹½è®¬è¯ 拽专讘讬抓 诪转谞讜转 è¯‡æ³¨è®œè®˜è®šè®¬è¯ è®œè¯‡è¯‡æ‹½è®œè®žè®œè½¬ è®›ç –è®œè®œè®—è½¬ 讟讬ä½è®œè½¬ 诇专讜诪讗 è°ž…

roma basic unisex puma beyaz unisex g眉nl眉k ayakkab谋 35357212

kè°‹z 莽ocuk klasik ceket outdoor ceketler s online satè°‹n al kjé…¶p h m denimjakker til herre pæ°“ nett fashiola sé…¶k adidas cf lite racer siyah erkek spor ayakkabè°‹ siyah sat谋艧 nike bayan spor ayakkabè°‹ sat谋艧 siteleri internationalist tren som en atlet adidas x…

mos eisley cantina

baby girl 3 6 months fleece sleepers clothes lot the 7 best baby bottles for breastfed babies of 2019 toy story disney pixar baby face spider baby sids mutant toy 4.5 cm baby rattle ball preschool educational learning toy carters just one you pink sher…

blue asics running shoes run repeat

best site for cheap nfl jerseysmens wallets australianike koston hypervulcnorth face t shirt

hockeyescorts

91 nike arik armstead jersey nfl san francisco 49ers backer long sleeve t shirt red buciki lasocki corset belt dress vestidos para pajes y damitas bailarinas de tela para ni帽a nike houston texans 59 whitney mercilus white elite jersey

wholesale mens womens dodge charger route 66 car t shirts bulk suppliers

dandelion pattern vintage diy photo album anniversary scrapbook 27 x best buy car and driver cdc 633 front and rear camera dash smittybilt 97712 xrc synthetic winch rope spare parts for scroll saw and kity coast hp3r rechargeable pen light review blowe…

adidas feminino originals nmd r1 primeknit cal莽ados branco cq2040

nike hoops elite max air laptop basketball teamcolumbia crown point 31 expandable spinner suitcase nordstrom rackchanel quilted lambskin xl jumbo flap baggirls kenzo jumper age 8

adidas kanadia trail erkek siyah spor ayakkabè°‹

cartier snubn铆 prsteny mè´¸da 2017 膷asopis mè´¸dn铆 dè°©msk茅 2017 kurtka damska zimowa top secret nike erkek g眉nl眉k y眉r眉y眉艧 600 air max motion lw nike file ve s眉re 艧ikayetleri 艧ikayetvar adidasi propel casual nike md runner barbati fluttershy 110 116 cl delux…

銈广儖銉笺å’銉笺å¤ç’©ç…Žå† é—冲畬澹?éŠ‰îƒ¾å„ nike air force 1 07 acw

altè°‹nyè°‹ldè°‹z erkek mont kaban zlat茅 nè°©u拧nice swarovski elements 10x10mm 拧perky milan ji艡铆膷ek mix from italy halterneck kl盲nning pink crochet dream maxi kl盲nning fræ°“n coster copenhagen living a style mayoral erkek 莽ocuk mont en iyi nike bayan spor ayakka…

sears timberland boots

saucony leather shoesnike air boots black thesolesupplierladies sandal ladies sandalwhere can i buy fake hair extensions

a bayern m眉nchen 茅s a torino meccs茅ben l谩tj谩k a tutikat

pirelli cinturato p7 madshus redline carbon classic cold svart opera maske meglerhus om xxl det trege markedet for sportsutstyr er proraso bartevoks nike air max tavas spec gré…¶nn 305944 coop extra nesoddtangen samsonite ergo biz pc trillekoffert 15.6

sandali di camminatori di marca appassionato di moda oliva

flere tusen i forskjell pæ°“ dyrest og billigst dagbladet pigger til joggesko sprit ny sporty spidi mc jakke byd gudbjerg sydfyn kakestativ 6 etasjer towering tiers lts stormshell daypack 30l green vanntett skitt fiske polo shirt pique classic herre styl…

damanhurcrea

vestidos primera comunion el corte ingles unisa bailarinas nike chicago bears charles tillman limited 1940s jersey youth navy blue 33 alternate throwback jerseys szpilki z ozdobnym obcasem topshop denim zip dress vestidos de novia en pronovias 2018

34. lacoste. croc gabardine cotton cap

borbonese luna medium filetto jet nero borse a spalla gum bauletto piccolo borchie vernice ver nero quadra charriol propone le sue creazioni orologi e gioielli in 2016 nuova inblu ciabatte rosso scarpe longra donna paillettes preppy chic zaino azioni t…

maystmarket

sac è„¿ dos north face borealis nike shox avenue nero blu unisex nike roshe run sort guld lotus espadrilles t shirt adidas decathlon kipling college up soldes

camicia da lavoro brembo manica corta azzurra hh025 rossini

gucci womens kingsnake cotton jersey t shirt sunkissed beige size medium gucci yankees shoes buy gucci light brown leather claudie horsebit peep toe platform gucci men sandals supreme canvas logo print beige black online womens gucci ghost shorts in re…

best cabin suitcase 2019

2017 newest style high waist bikini sexy womens swimsuit crop top short sleeve swimwear bathing suit black beachwear swim wearglamorous magic crystal white sequin dressback 2 mentality dress blacknewest elegant lace short homecoming dresses

s oliver dames sneaker met zacht voetbed. nieuwe collectie

ferastrau unghiular stern cu panza circulara si suport msgeaca lunga bleumarin matlasata columbia de primavarasutien baie post mastectomie lenjerie intima dama anybodydezactivate parfumuri 葯i alte produse b膬rba葲ii femei

plastov茅 n谩ramky barevn茅 9ks

billiga kl盲nningar fræ°“n asos fæžšr kvinna pæ°“ rea kinetix herbert w beyaz kadè°‹n sneaker ayakkabè°‹ siyah puma kazak hope ivy omlott tea kl盲nning kurtka ci膮å¶owa w kwiaty czarny bonprix kurtki damskie czarne w bonprix dunjakke barn skogstad nike 852489 001 me…

beauty emily womens long formal evening dresses appliques

tina holly couture kjole ankellang med perlersamsé…¶e samsé…¶e jakke lucca parka blackspejl ralph sé…¶lv egne mæ°“ltenson regnså¿™t dameté…¶j se billigste pris nu

stivaletti caprice

trolley da spesa palestra firenze t shirt disegno scarpissima on line harry styles lion ring bauletto 47 brand cappotti per cani piccola taglia espadrillas dove le vendono

womens ivory cable knit sweater dress

hill burry geldbæžšrse damen vintage echtleder portemonnaie puma suede platform pink puma men women cheap puma ikea hat 40. jubil盲um in deutschland bild 7 spiegel damen mode soft schalen push up bh set 2 teilig slip rot gr gore bike wear base layer unter…

superman logo t shirt

professional scissors japan samurai scissors hairdressing cutting thinning set high temperature metal hose 300 series ss flexible hose fast pinewood derby car school seamless background. education learning college officemax black fax refill rolls outdo…

earndptwcu

las mejores botas vaqueras para hombre portugal blank home long sleeves soccer country jersey buty materia艂owe m臋skie j crew plaid dress vestidos cortos pegados de encaje zapatillas domyos ni帽o

striped tweed v neck dress

best price on the market at italist moschino moschino couture mini bag shoulder bag women moschino couturedior cologne royale fragrances perfumesshoulder womens mansur gavriel light pink lined folded leather bag rosa jeek storecoach tabby fold colorblo…

lace appliqued long sleeves sheer bodice velvet purple evening dress mermaid prom dresses 2018

sixy model school school facebook1800s mens costumefree shipping hot selling men halloween costume party carnival costume german beer men oktoberfest costume m xxl in anime costumessouth bay hospital office

adidas zx 500 og leder

prix des verres correcteurs progressifs robe rouge courte moulante coque kd samsung a9 gold robe fluide color茅e etui samsung tab 3 7 coque coach samsung galaxy j6 pro sac lacoste femme cuir promo shoes

offerta scontate nike air max 97 hyperfuse scarpe per uomo

prezzi west highland white terrier tosaerba elettrico grizzly 1851 a q 360 1800 watt 51 cm bigz die best wishes occhiali e occhiali felpa con cappuccio new givova uomo donna unisex sport relax comfort giosal marcolin occhiali da vista uomo donna 801 ca…

nike air max 720 red black

soulier chic pour femme tr猫s classe escarpins chaussures femme laura shoes reebok club c 85 s shine royal dark blue white club embroidery futura t shirt 100 blanc zx flux pour femme vestes courtes pour femmes 2018 nouvelle arriv茅e mens costumes de mari…

veste longue costume femme

everton jersey converse cap green brooks glycerin 9 womens gold nike zip up jacket mens white diad猫me de mariage sac plage personnalisable les v锚tements 脿 la mode coque nike samsung not 8

mens black and white leather jacket

nina girls zelia jeweled satin dress shoescarters baby girl 4 piece pjs ballerina pjs 4pc pajamas set 9 12 18 monthsivana lace dress white beigebaby boy sailor christening outfit. blue

è¯ªç –æ‹½é©»è®¬ ç –è¯ªç – é©»ä¸“è®¬è°žä½ 101 1515 prince

xxl handtasche badehose 152 nike sb zoom stefan janoski canvas damen dirndlbluse langarm spitze t shirts frauen motiv wo anzug kaufen damen shorts online bestellen heine sweatshirt mit bluse

profesjonalna szlifierka k膮towa 2w1 900w gift home dom

1984 jeep cj 10 aircraft tug diesel 3.3 automatic jeeps men green leather jacket chests of drawers ikea best games for family game night under armour challenger ii knit warm up tracksuit set anthracite the 12 most fun llama party supplies catch my part…

angkorly chaussure mode espadrille slip on plateforme femme pom pom frange corde talon bloc 3.5 cm

donna vestiti for abiti da sposa high low tulle abito da ballo express nero vestito ross bianco vestiti vestitolily plus size vestiti semi corporate attire cool shoulder vestito ladies estivo maxi vestiti

moda gonna a balze con orlo trasparente abbigliamento

michael kors hayes med trifold coin purse wallet from michael michael kors hayes collections michael kors 18ss tagged snap tote dbl sided mercer annie blk from gucci alma small michael kors leather fulton chain medium shoulder tote hobo violet purple m…

pochette du soir

magazine 6 mois meilleures enceintes salon vetement polo ralph lauren magasin d茅griff茅 coque chanel samsung galaxy tab s3 coque eellesse iphone i plus levis coupe slim dsquared basket homme pas cher

100 najboljih ideja kako ukrasiti sobu za djetetov ro膽endan

7 1 éä½ä¼ªèŸ½å–‚éç»´ 尾喂尾ä½å§”伪 纬喂伪 蟿慰 é伪ä½æ…°é伪委蟻喂 clickatlife æ…°å–‚ 20 蟺喂慰 è …èŸ»ä¼ªå§”è”šèŸ¼ è æ…°è ‰èŸ½èŸ¿è”šèŸ¼ 蟿ç•èŸ¼ 伪纬慰蟻维蟼 style backpack 蟿蟽伪谓蟿伪 蟺ä½ä¼ªèŸ¿ç•èŸ½ çº¬è €è°“ä¼ªå–‚é蔚喂伪 replay è”šèŸºè …è°“è €æ¸è”šèŸ½ 蟿蟽伪谓蟿蔚蟽 è ‚è”šå–‚èŸ»æ…°èŸ½ è ‚å–‚ä¼ªèŸ½èŸ¿å–‚ archives 蟿蟽伪谓蟿蔚蟽 ä½ä¼ªæ¸èŸºèŸ¿èŽèŸ»è”šèŸ¼ led e14 ä½ä¼ªæ¸èŸºèŸ¿èŽèŸ»è”šèŸ¼ led ä½ä¼ªæ¸èŸºèŸ¿èŽèŸ»è”šèŸ¼ èŸºèŸ»æ…°è †æ…°è°“èŸ¿ä¼ª anatomika 蟽伪谓未伪ä½å–‚伪 bion…

銈般å„銉?銉曘儹銉笺儵 銉曘儵銉兗銉椼儶銉炽儓闀疯病甯?浣愪箙骞冲簵 璨峰彇

m臋skie dresy livergy b盲sta boxare roliga tecknade tryckta 12 kaxiga och coola træžšjor med tryck fæžšr barn baaam ajè°©nd茅kæžštletek trè´¸nok harca rajongè´¸knak kobieca delikatna bia艂a bluzka gorset 1045 l puma st runner v2 kadè°‹n b眉y眉k beden takè°‹m gæžšr眉n眉ml眉 abiye…

womens star one piece bathing suit

gucci interlocking chain black leather crossbody bag catawikigirard perregaux vintage 18 ct gold automatic kal. 3200 refsuper 8 atelier hotel motel sneakers and accessoriesthe bogg bag the perfect beach

stuffed animals plush toys target

pink glitter bow tie tartan throw blanket light weight wool silhouette of people dancers with black white background stock video footage storyblocks video hat and scarf set handmade hat and scarf with cowboy skechers 銈广å™éŠ‰å†¦å„ŠéŠ‰ï½ƒå…—銈æ’伄銈广å™éŠ‰å†¦å„ŠéŠ‰ï½ƒå…—銈æ’å£éŠ‰å¬¨å…—éŠˆî‚ å…— 銈广儖銉…

rajo laurel gowns

pantofi sport femei reebok classic freestyle hi 2240 éä½ä¼ªèŸ½å–‚é苇蟼 尾喂尾ä½å–‚慰胃èŽé蔚蟼 纬喂伪 蟿慰 蟽蟺委蟿喂 tarzan spark tarzan herre spark og tilbehé…¶r sport 1 14karè°©tos arany pancer nyaklè°©nc arany klasszikus nyaklè°©ncok é‘·î„å§ªæ¿ æ°±ç¤‚ç忕Ξéˆå¶…皥璩e簵 ç忔磱ç‘濇檪çæ°æ«„绂湇 jf绂湇 chlap膷enskè°© detskè°©…

custom made adidas boots

champagne colored flower girl shoesnike jordan 1 menpersonalized gold chainbrown polo shirt ralph lauren